If we found a sign of alien life in space, one of Professor Lisa Kaltenegger’s first questions would be: what colour is it?

But even such a world-leading expert in the hunt for habitable worlds doesn’t expect to have a telescope strong enough to spot a little green man or purple woman.

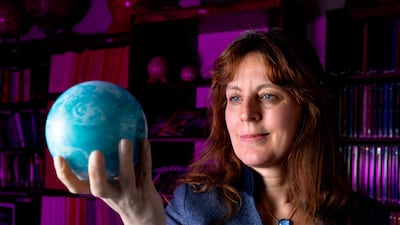

What Prof Kaltenegger can do instead is turn to the vividly hued jars of lifeforms she’s assembled in her lab at Cornell University, ready for this moment.

Thanks to her life’s work spent analysing Earth’s history and biosphere, we know how its bright and beautiful organisms would look to a clever alien with a telescope.

Even small lifeforms such as pink algae leave "fingerprints" in the light that are transmitted vast distances through space.

By the same token, that means Prof Kaltenegger can use her red, green and yellow jars to determine what “bio-pigments” to search for in an alien world; our home planet as a sort of Rosetta Stone.

Life on Earth has changed the colour and atmosphere of our world and the same telltale signs could give the game away even for incommunicative aliens.

There could be trillions of rocky worlds out there but the cheerful scientist would be happy if we discover only one more that supports life.

“Because it’s so hard to do it, finding one means that there must be so many more,” the distinguished astrophysicist tells The National. “When I would look up at the sky, then I would know that it must be a cosmos teeming with life.”

Prof Kaltenegger, 47, knows exactly how hard it is to find alien worlds because she is among the top scientists on the quest.

She was behind the discovery of two promising Earth-like planets, Kepler-62e and Kepler-62f. She's shown that if an alien looked at Earth, the telltale signs of life have been there for about two billion years.

And if an alien planet's light reaches us, she can figure out where it's come from because of clues it contains "like stamps in a passport".

The analogy is one of many in Prof Kaltenegger’s jolly new popular science book, Alien Earths: Planet Hunting in the Cosmos.

Filled with zany metaphors, Doctor Who references and stories of her childhood in Austria, the beginner’s guide to finding alien life is meant so that “everybody can find themselves in there”.

That includes her daughter, Lara Sky, and women and girls who aspire to thrive in a field historically dominated by men.

To solve such a profound question, “your best bet is to get people in a room who have very different ideas, experiences and backgrounds”, she says.

Where is everybody?

What we know is this. There are about 100 billion stars in our galaxy. Many of them – about one in five, reckons Nasa – are orbited by rocky planets about the size of Earth that sit at what could be a habitable distance from their sun. That’s potentially billions of Earths. And that’s just our galaxy, itself one of billions.

So, where is everybody? Theories for the “Great Silence” range from the mundane (perhaps primitive humans just aren’t that interesting to space-faring aliens) to the chilling (maybe any great civilisation is bound to destroy itself).

Or maybe the Earth really is unique? Prof Kaltenegger doesn’t want that to be true.

“I really hope it’s not special. I’d rather be not special and not alone,” she says, laughing.

An icon of hers is Carl Sagan, the late American scientist known for his moving reflections on the smallness of our “Pale Blue Dot” in the vastness of space.

“Think of the rivers of blood spilled by all those generals and emperors so that, in glory and triumph, they could become the momentary masters of a fraction of a dot,” Sagan wrote in 1994.

A pioneer of the search for alien life, Sagan said he would “hate to die and never know”. Sadly he did, aged only 62.

Does Prof Kaltenegger think she will ever find out? “I really hope we can do this in my lifetime,” she says. “And this is why I’m working hard to get it done.”

As the founding director of the Carl Sagan Institute to Search for Life in the Cosmos, she has built a team of tenacious scientists from many disciplines to create a uniquely specialised toolkit to give it the best shot.

But she has a typically positive way of looking at it even if the search takes longer than her lifespan.

“The beauty of science is that it stretches through the ages. I get to do something because Carl Sagan figured something out, because Galileo figured something out, Marie Curie did something,” she says.

“Even though these people aren’t here any more, their ideas still vibrate through our lives. Our ideas, hopefully, will enable incredible scientific discoveries in the future.”

Like Sagan, and some of the astronauts who have seen our world from above, learning about space makes Prof Kaltenegger reflect on our place in the universe, but she does so with a feeling of optimism rather than loneliness.

“If we can figure that out, we can figure things out like climate change, like conflicts on the Earth,” she says. “I don’t know when. I’m really hopeful it’s going to be sooner rather than later.

“It gives me a lot of hope, instead of thinking that I'm small and insignificant.”

Scientists have a powerful new tool in the form of the James Webb Space Telescope, which can capture zoomed-in pictures from almost unfathomably far away.

The light that hits Webb has been on a journey from the earliest days of the universe. That means we are effectively seeing into the past. Any alien race we detect might no longer be there. We might be gone, too, by the time our light reaches them.

Amazing images from the James Webb Space Telescope – in pictures

Still, even discovering the remnants of life would prove we are not unique and “if we’re lucky, for the first time ever, we have the instrument to do it”, Prof Kaltenegger says of Webb.

Artificial intelligence is being used to find patterns in data and it is easy to forget that we are living in an “era of exploration”, she says.

Yet it’s because humans are actually “so bad at finding it right now” – no disrespect to engineers doing their best, Prof Kaltenegger hastens to add – that she says finding one more Earth would imply there are really many more.

What if we do? It would be the news story of the century but it would probably come in stages, as excited scientists present their findings and others try frantically to confirm or deny them. Can we be sure this is life? What even is life? Nasa calls it a self-sustaining chemical system capable of Darwinian evolution. But the universe sometimes behaves in unexpected ways.

Then there is the question of how to approach our newfound aliens. Who should speak for the Earth? Should we try and communicate at all? How? It might be like trying to talk to a jellyfish.

Until that day, we still don’t know how rare Earth is.

If Prof Kaltenegger is unlucky, signs of life might exist on only every millionth or billionth planet. Then even her heirs could struggle to build a telescope powerful enough. But “why would it be that rare?”, she asks.

“Wouldn’t the biggest surprise be if we find nothing?”

'Alien Earths: Planet Hunting in the Cosmos' (Allen Lane, £25) by Lisa Kaltenegger is available now in hardback.