Researchers say newly examined fossils prove that the centre of Greenland was once home to a flourishing tundra landscape when the ice there melted away more than a million years ago.

They claim their discovery shows the fragility of the ice sheet and provides a snapshot of what the world could look like in the future if global warming and sea-level rises continue at their current trajectory.

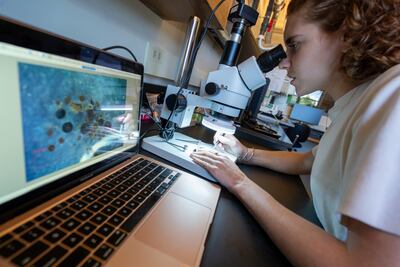

The team of scientists from the University of Vermont (UVM) examined a few inches of sediment from the bottom of a two-mile-deep ice core extracted from the very centre of Greenland more than 30 years ago.

They were amazed to discover soil that contained fossils of willow wood, insect parts, fungi and a poppy seed in pristine condition.

However, the authors of the study warn that such melting took place even before human-made climate change, providing a stark warning for the future if climate change continues on its course.

“In this new study, we found that at some point in approximately the last million years, at least 90 per cent of the Greenland ice sheet melted,” UVM's Halley Mastro told The National.

“These findings tell us that the Greenland ice sheet was sensitive enough to natural climate changes, with lower levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere than today, to almost entirely melt and significantly change global sea levels.”

She warned that similar melting of the Greenland ice sheet today would contribute about 20 feet to sea levels globally, impacting millions of people in coastal cities such as New York, Boston, Jakarta, Miami and Mumbai.

In 2019, Paul Bierman and his team from University of Vermont re-examined another ice core taken from Camp Century, near the coast of Greenland, in the 1960s.

They were stunned to discover twigs, seeds, and insect parts at the bottom of that core, revealing that the ice there had melted within the past 416,000 years.

In other words, the walls of the ice fortress had failed much more recently than had been previously imagined possible.

For their latest study, they then turned their attentions to examining a 1993 soil sample called GISP2 – held at the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility in Lakewood, Colorado.

The GISP2 soil sample showed how the centre of Greenland was ice-free for many thousands of years, enough time for soil to form and an ecosystem to take root.

If the ice covering the centre of the island was melted, then most of the rest of it had to be melted too, researchers added.

Their research seems to support findings by Joerg Schaefer at Columbia University who published a study in 2016 suggesting that the current Greenland ice sheet could be no more than 1.1 million years old.

It found that there were extended ice-free periods during the Pleistocene and that if the ice was melted at the GISP2 site then 90 per cent of Greenland would be melted also.

This was a major step towards overturning the long-standing story that Greenland had been frozen solid for millions of years.

“It will take many centuries to a few thousand years before all the ice is gone from Greenland,” Ms Halley said.

However, she cautioned that much future warming is already certain because atmospheric carbon dioxide levels will remain high for tens of thousands of years.

“These results confirm that the Greenland ice sheet was more sensitive to natural climate changes than we once believed in the past and thus is more susceptible to melting catalysed by human-induced warming.

“This helps us to know we need to act with more urgency to decrease emissions and work to remove carbon from the atmosphere that we have already emitted.”

The study was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.