Tulip trees could help us fight global warming because of the kind of wood they are made of, scientists believe.

A chance finding at a botanic garden revealed the special type of wood that appears especially good at storing carbon.

Trees are natural carbon sinks that remove CO2 from the atmosphere, where it contributes to global warming.

But it is believed ancient tulip trees, also known as liriodendron, may have evolved millions of years ago to store larger amounts of carbon.

“It was bang in the middle of when the planet was undergoing a big change in atmospheric CO2 levels,” said Raymond Wightman, who runs advanced microscopes at Cambridge University's Sainsbury Laboratory.

“The planet went from very high CO2 levels to then relatively low CO2 levels. The plants might have adapted,” Dr Wightman, a co-author of the new research, told The National.

“We’re just starting to wonder, is it something about this new wood structure that allows it to lock in more carbon?”

The species are found in North America and Asia and grow quickly, which could make them suitable for newly planted forests.

They are already used in plantations in parts of East Asia to “lock in” carbon, said a second co-author, Jan Lyczakowski.

Their rapid growth, as well as their hunger for carbon, may both be linked to the special kind of wood, an “intermediate” type between hardwood and softwood.

It was discovered by British and Polish researchers who took samples from Cambridge University's botanic garden, where the Sainsbury Laboratory is housed.

“We just decided, summer before last, just because we could, to survey as many trees and shrubs in the botanic garden as possible,” Dr Wightman said.

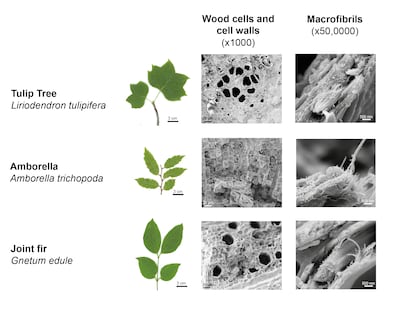

Preserved in liquid nitrogen at -210°C and magnified by 50,000 times under a microscope, the tulip tree samples came as a surprise to scientists.

The two surviving types of tulip tree both have much larger fibres, known as macrofibrils, than their hardwood relatives.

“Both of them had a structure that we’ve not seen before, and we’ve looked at a lot of wood structures in our microscope,” said Dr Wightman.

Using trees as a carbon sink is a common green initiative, especially as they can bring other benefits such as shade and wildlife habitats.

Research has found that planting as many as a trillion new trees on Earth could put a huge dent in the planet's carbon problem.

There are also man-made techniques, known as carbon capture and storage, that claw back CO2 waste before it hits the atmosphere.

However, an over-reliance on these methods can be seen by environmentalists as greenwashing that avoids cutting CO2 emissions in the first place.

The article Convergent and adaptive evolution drove change of secondary cell wall ultrastructure in extant lineages of seed plants, by Jan Lyczakowski and Raymond Wightman, is published in the journal New Phytologist.