Seven years ago Pir Arkam became the first person to build a 3D printer in his native Pakistan. His alma mater, Mehran University of Engineering & Technology, still boasts about his achievement in marketing materials – even though the first object he produced was a whistle incapable of producing sound.

However, after thousands of attempts, a Master's degree in robotics and automation and a move to Dubai, Mr Arkam's work is much more than a passing university hobby. His two year-old start-up, Proto21, now provides life-saving materials to those on the frontline of the Covid-19 response in the UAE.

His story is one of many in nearly every corner of the globe of a 3D printing workshop transforming its output in the face of this pandemic. For the past few months, start-ups, labs at universities and major multinationals like GE, HP and Volkswagen have been 3D printing much-needed masks, face shields and ventilator splitters to hospitals and medical professionals.

For Mr Arkam, a business owner with 17 employees and numerous contracts, news of the novel coronavirus was scary.

"When the pandemic began, business went away. I thought, we will not be able to pay salaries. But then suddenly I got a call," he says. The words were a welcome relief: "You've got a project."

Prior to the pandemic, the Proto21 facility in Jebel Ali operated up to 18 hours a day, its 40 printers churning out more than a thousand projects for some of the countries biggest brands over its two years in business.

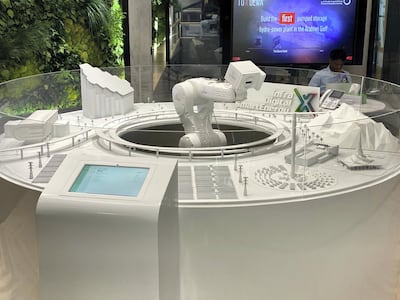

For Dubai Expo2020, for example, Mr Arkam and his team worked with UAE students to turn ideas into functional prototypes, for a lesson on innovation. For the UAE Ministry of Defence, Proto21 made a topological map of the entire Middle East. A 3.5 metre-long drill bit at Adnoc's Abu Dhabi headquarters came out of the workshop, and Emirates Airlines relies on Mr Arkam for 3D-printed parts for its maintenance department.

But today, those 18-hour shifts look a bit different.

Proto21 is printing thousands of face shields every week for Dubai Police, Dubai Health Authority, as well as for hotels and retail outlets like Sacoor Brothers, and individual doctors who get free deliveries to their door if they ask.

The team is using different designs pulled from open sourcing, like the design Apple made available, and their own trial and error. Depending on if the shield will be used by doctors working a 12-hour shift in a clinical setting, or a police officer out on patrol during the sticky summer months in Dubai, the face masks are tailored to those needs: indoor or outdoor, length of wear and temperature exposure. These variables can be challenging to design for, it is not as straightforward as simply pressing 'print'.

This production method, also known as additive manufacturing, is a process of making three dimensional solid objects from a digital file. Proponents of 3D printing say it is the most precise, cost-effective and fastest way to produce goods, allowing complex shapes to be made using less material than traditional manufacturing methods.

The 3D-printed object is made by laying down successive layers of material, usually plastics, metals or polymers, until the object is created. Each layer is a thin, horizontal cross-section of the final product.

Prior to Covid-19, the global 3D printing materials market size was projected to reach $3.78 billion (Dh13.88bn) by 2026, growing by a compound annual basis of 12 per cent during the forecast period, according to a May report from Fortune Business Insights.

Aerospace will be one of the main growth drivers for this market, according to the report, which points out that the industry has been harnessing 3D printing technology for the past few decades to build design prototypes.

Recent breakthroughs using 3D printing show massive potential, according to Fortune. In Europe, for example, additive manufacturing is being used to produce implants and prosthetics for the healthcare sector. In Asia-Pacific, 3D printing materials are used in industries like automotive, healthcare and defence, according to the report.

Within a few short years, 3D printing has gone from a niche manufacturing method to opening new frontiers for scientific research and modern production. The Covid-19 pandemic has made it a mainstream solution as supply chains were hindered by the public health response, and demand surged for personal protective equipment (PPE) to help contain the virus' spread.

Mr Arkam is used to a challenge. He sold his car in Pakistan to start his 3D printing business in Dubai in 2018. He started out alone, offering training courses on the production method to businesses in the GCC.

Joseph Group, a large manufacturing company in Dubai that makes much of the signage throughout the UAE, took him up on his offer to learn the basics of 3D printing. They were so impressed by what he taught them that just a few months into business, Mr Arkam sold his company to Joseph Group for an undisclosed sum, retaining 25 per cent ownership but ceding control.

"It was the best decision of my life," Mr Arkam says. The acquisition allowed him to invest in equipment and quickly grow the business, which came easy for an entrepreneur obsessed with sales.

"Wolf of Wall Street is my kind of story," he says. Prior to starting Proto21, he worked at a call centre making 150 calls a day, selling 3D technology to businesses in the UK. It was good practice, he says.

But now, his purpose is to be of service.

These days, instead of producing product models for Adidas or Pantene, the company is printing ventilator splitters for Sharjah Hospitals so that one ventilator can treat multiple patients. It is also making Charlotte valves that can be attached to a snorkelling mask to make it a reusable full-face PPE for the doctors of Al Rashid Hospital and some Abu Dhabi ambulance staff. Some of this work is being done completely free of cost.

"From childhood I was interested in robotics and electronics. I would break my toys and see what's in there," he says.

He was first professionally introduced to 3D printing when he was awarded a scholarship for an exchange semester at the University of Huntsville in Alabama in 2012.

"I was fascinated," he recalls. "It was the world’s first self replicating device. A 3D printer can 3D print half of its parts for another 3D printer."

He decided he wanted to introduce this technology to his home country, and made building a printer his final year project.

"At that time it was more as a hobby," he says.

But today, he dreams of replacing limbs and teeth using bio-ink derived from someone's DNA. He thinks about sending a 3D printer to Mars, and using Martian soil to build homes.

For now, he is helping Earth overcome one of its biggest challenges. For someone who could not afford the materials he needed to do his work only two years ago, Mr Arkam is already exceeding all of his own expectations.

Q&A: Pir Arkam, founder of Proto21

What successful start-up do you wish you had started?

Proto21 was my dream and that’s what I would start again if I get a chance again. I want to become an industrialist. My goal is to use technology to solve problems and create jobs.

What's next?

Future plans are to start a renewable energy based start-up or an engineering DIY education kits company. I want to build factories and become the leading manufacturer of the world.

What has your growth journey been like?

Business expansion has been overwhelming in the short span of two years. From myself alone to a good team of 18 people, from one single machine to 40 machines.

If you could do it all again, what would you do differently?

I would work better on digital marketing campaigns and join Joseph Group earlier.

What might surprise people about the potential of 3D printing in the next decade?

3D printing is going to be a part of everyday life. There will be a 3D printer in everyone’s home and essential manufacturing tools in various industries. You will be able to 3D print body organs. Martians will use it as an essential tool while establishing Mars colonies. 3D printers in combination with artificial intelligence will develop communities and facilities on their own in remote areas, and even outside, this world.