A look back at prominent people from the world of business who died in November:

Abdul Wahid Al Rostamani

He started out in his early twenties with a small bookshop in Dubai but over the decades Abdul Wahid Al Rostamani helped build a business group that spanned car sales, property, retail and IT.

Al Rostamani, the chairman of the conglomerate that bears his family’s name, died on November 3 at age 83. The group is perhaps best known as the owner of Arabian Automobiles, the sole distributor for Nissan, Infiniti and Renault vehicles in Dubai and the Northern Emirates.

Arabian Automobiles was established in 1968. Al Rostamani and his brother Abdullah had expanded into general trading in 1957 under the name Central Trading Company, three years after opening their bookshop, Al Ahliya Library, in Dubai, which at the time was one of the seven Trucial States that would later unite to form the UAE.

Al Rostamani conveyed his group’s ethos in a statement on the company website: “Our priority will be to continue to enrich the people’s life experience in a measured way and not compete on size alone.”

Al Rostamani’s brother Abdullah died in February 2006 at age 74. In August 2013, Al Rostamani Group, under Abdul Wahid’s leadership, donated Dh10 million to Dubai’s Al Jalila Foundation to fund medical research, scholarships and health care for those who could not otherwise afford it. Al Jalila Foundation in turn memorialised Abdullah by naming a lecture hall after him.

More than 4,000 people work for Al Rostamani group.

Nevine Loutfy

The first woman to head an Islamic bank in the Arab world was found murdered in her Cairo home on November 22. Nevine Loutfy was 64.

She had been chief executive of ADIB Egypt, a unit of Abu Dhabi Islamic Bank, since 2008.

“It was an honour to have known such a great person and my heartfelt condolences go out to her family and colleagues,” Tirad Al Mahmoud, the chief executive of ADIB, posted on Twitter.

Colleagues remembered her as a mentor to many women.

She graduated from the American University in Cairo (AUC) with a degree in economics in 1974 and started work at Citibank in 1976 as a financial analyst in the bank’s Cairo office. She held many international posts for Citibank before her time at Adib Egypt.

In an interview in 2010 with AUC Today she recounted how, in 1982, she requested her first international posting.

“My boss then asked, ‘What will we do with your husband?’ And I replied, ‘You never ask a man what you will do with his wife.’”

The bank sent her to Italy.

Dwayne Andreas

Dwayne Andreas, the farmer’s son and college dropout who turned the grain-processing company Archer Daniels Midland into “the supermarket to the world”, then saw it rocked by a price-fixing scandal, died on November 16. He was 98.

Under Andreas, the company changed the agricultural world. Andreas used his influence and friendships with politicians ranging from Harry Truman to Mikhail Gorbachev to encourage subsidies for corn and grain farmers, maintain huge overseas markets and help turn ADM products, including high-fructose corn syrup, into staples of the American diet.

Andreas, who became chief executive of ADM in 1970, stepped down in 1997, the year after the company pleaded guilty to price-fixing charges and agreed to pay $100m in fines. The scandal also sent three men, including his only son, Michael, to prison. Andreas left the chairman of the board post in 1999.

ADM was a sleepy regional agricultural processing company when Andreas became chief executive. His use of political clout – and his aggressive acquisition of smaller companies and expansion into new markets – built ADM into one of the world’s largest agricultural processing, marketing and distributing companies.

One key to Andreas’s success was viewing the world as a global marketplace earlier than his peers. ADM acquired oilseed processing plants in Europe and South America in the 1970s, then brokered grain sales to the Soviet Union and expanded into Japan. By the early 1990s, ADM was operating in Singapore and China, according to its website.

The company produces soybean oil, ethanol, animal feed, cocoa products and vitamin E, in addition to the syrup. Its sales pushed towards $20 billion a year during Andreas’ last years in charge and now top $60bn.

Andreas was born in 1918 near Worthington, Minnesota, to Mennonite farmers Reuben and Lydia Andreas. He dropped out of Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, to help his father and older brothers take over a bankrupt grain and feed business in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. The company, Honeymead, prospered, and in 1945 the family sold most of its assets to Cargill, a Minneapolis commodities firm that is now one of ADM’s biggest competitors.

When the family’s remaining soy processing plant burnt down, the Andreas brothers rebuilt it as the nation’s largest such facility, selling it in the mid-1960s and moving on to ADM with the purchase of 100,000 shares in the company.

Andreas Vgenopoulos

Andreas Vgenopoulos, a Greek lawyer turned business tycoon, died on November 5 of a heart attack. He was 63.

Vgenopoulos was vilified as the man who precipitated Cyprus’ banking crisis in 2012, which led to an EU bailout and a one-time levy in 2013 on all uninsured bank deposits over €100,000 (then about Dh473,000). He was also accused of corrupt lending practices, first in Cyprus and then, last month, in Greece, a charge he strongly denied.

At the height of his success, Vgenopoulos acquired a string of businesses including Marfin Popular Bank, a passenger shipping firm, Greece’s largest food company, a private clinic and Greece’s ailing state airline, Olympic. Recent years, however, had seen a reversal of fortune. While he held on to most of his acquisitions, their value shrank considerably.

Vgenopoulos was forced to sell Olympic to competitor Aegean Airlines. His bank, renamed Cyprus Popular Bank, was taken over by the Cypriot government, divided into “good” and “bad” parts. The “good” unit was sold to other banks and the “bad” was shuttered in 2013.

Vgenopoulos was a champion fencer in the 1970s and early 1980s and competed in the 1972 Olympics in Munich. He was also involved for a time as a minority shareholder of the football club Panathinaikos.

Rick Medlin

Rick Medlin, a former collegiate gridiron player who became chief executive of Fruit of the Loom and an advocate for fair treatment of workers, died on November 27. He was 68.

He had been president and chief executive of the Kentucky-based clothing company from 2010 until his death of a heart attack while he was at his home in South Carolina. It was in that state that he was born in 1947 and attended Clemson University on an American football scholarship. A running back, he accounted for 280 total yards from scrimmage during his three seasons as a Tiger.

Medlin left college with a master’s degree in education. His education in business would come later.

At a travel-industry conference last year, he recounted a story from his first stint as a plant manager. He worked hard to improve worker safety – an issue that he would continue to emphasise throughout his career. But when he told his boss that he had improved worker safety by 50 per cent, his boss said he had to do better. “That’s when Medlin realised he had to up his game and decreased the number of plant accidents by 100 per cent,” according to a report in the Bowling Green Daily News.

Fruit of the Loom received the US federal government’s 2013 Large Business Award for Corporate Excellence. In accepting the award at a ceremony in Washington attended by the US secretary of state, John Kerry, Medlin said the company’s core value was “respect for people”. When workers at a plant in Honduras unionised, he said, the company tried to make the change work as smoothly as possible.

“As a result of this model,” Medlin said, “we completed the first real collective bargain agreement in the apparel sector in Central America in 2011. We have now replicated that model successfully in a second Honduran plant and we are currently in collective bargaining for a third plant.”

He did not mention that the company had initially reacted by closing the first plant to unionise. The company later reopened the plant and its eventual acceptance of the union was widely praised.

Fruit of the Loom is owned by Berkshire Hathaway and has about 30,000 workers in 17 countries.

Jay Forrester

Jay Forrester, a remarkable inventor whose creations included magnetic-core computer memory and the field of system dynamics, died on November 16. He was 98.

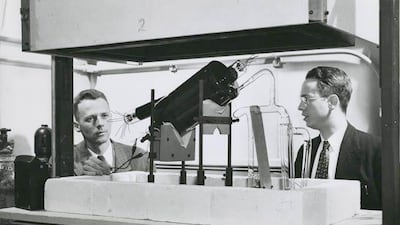

Raised on a ranch in Nebraska, by the time he was in high school he had built a wind-powered generator to electrify the homestead. He went on to graduate studies in electrical engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, after which he joined its Servomechanisms Laboratory, which studied the use of feedback-based controls for mechanical devices such as gun turrets.

Forrester then led MIT’s Project Whirlwind in the nascent field of digital computing. His work on magnetic-core computer memory, an early form of RAM, used an early form of binary language, with tiny metal rings that were strung on wires and sustained a magnetic field. If the field’s polarity went one way, the ring was a 0; if the other way, a 1.

His widest insight came after he studied a General Electric factory that was having inventory problems.

He came to realise that the factory itself was a feedback system and this insight led him to found the field of system dynamics. He later expanded it to view the entire world as a feedback system, and viewed endless growth as a risk to this system.

In an interview with The New York Times, the University of Reading business professor David Lane summarised Forrester's achievements: "Here you have a man who starts as an electrical engineer, so he understands current flowing down wires and charge accumulating in capacitors. Then he moves into servomechanisms and feedback control. Then he makes this remarkable imaginative leap, which is that those ideas are a way of threading together parts of a system, all connected by feedback loops. And once you start thinking like that, you've created an entirely new way of thinking."

* Agencies and The National

Follow The National's Business section on Twitter