The effort by Spain’s Socialist government to control apartment rents in one of the developed world’s more buoyant property markets is off to a rocky start.

In May, two months after imposing a battery of rent-suppression measures for new leases, rents rose at a 7.5 per cent annual pace, according to property website Idealista.com, which supplies data to Spain’s central bank. That was an acceleration from 6.6 per cent in March when the measures were enacted.

The new rules for privately owned apartments in Spain’s $5.8 trillion (Dh21.3tn) home market were meant in part to counteract speculation and conversion into Airbnb-type rentals. Tourist flats now exceed a quarter of the sunny, beach-filled Andalucia market and total 18 per cent in Catalonia, the region of Barcelona, Spain’s most visited city and a foreign-investor magnet, according to property website Fotocasa.

From Berlin to New York, governments are wrestling with how to keep tenants from being priced out of their neighbourhoods. Fingers point at stagnant wage growth, moribund government support, international buyers and surging purchase prices. These are some of the hallmarks of 21st century urban housing markets, and they are proving to be an unprecedented challenge for governments struggling to fix them with regulations.

Berlin is going even further than Spain, with plans to freeze rents for five years and give tenants the opportunity to demand reductions if rents are determined to be too high. German real estate stocks slid after the programme was announced.

Similar measures are being contemplated across Europe and the world. In New York, state legislators just completed the biggest rewrite of rent regulations in decades, eliminating most tools landlords have used to raise regulated rents.

In Spain, the new rules limit annual rent increases for five years to the inflation rate, currently 0.8 per cent. That’s not happy news for landlords, although after that period is over they can raise, or lower, them as they wish, in a new contract. The prices quoted by Idealista reflect what landlords are asking for in new contracts.

Spain’s housing secretary Helena Beunza says rental rates will begin moderating as the state creates more affordable housing, and when new contracts kick in with the five-year caps, up from three years previously. The government is also devising new public-private partnerships and reference prices for tax deductions for landlords who don’t overcharge, she said in an interview. The new cap is seven years for institutional owners like Blackstone, which bought Spanish homes when the market was plagued by overbuilding.

“The big institutional investors are specialists, they’re opportunistic and will focus on where the outlook and conditions are most favourable,” said Joe Lovrics, who runs Citigroup’s Iberia markets desk in Madrid. “They look at these rules and say: ‘If this is permanent, we’ll look elsewhere.”’

In fact, the Development Ministry in Madrid plans more regulations. Economists are divided on whether the limits will backfire.

While some insist they will restrain hikes indefinitely, many say landlords will react by starting new contracts at higher initial rents, or converting more property into short-term Airbnb-type rentals, eliminating supply for permanent residents and driving up rents.

“It’s a classic economics problem, but it doesn’t have a classic supply-and-demand solution,” said Alejandro Inurrieta, an economist who is writing a book on the country’s rental market. “In fact, the problem of runaway rents stems more from escalating home prices than people realise.”

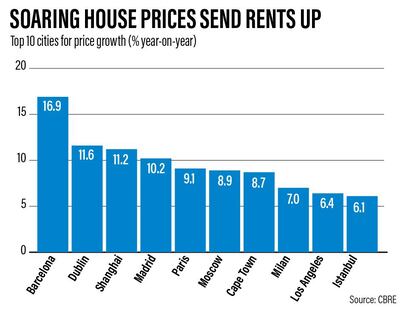

In the Madrid region, for example, economists like Mr Inurrieta say the 34 per cent increase in home prices over the past three years is more to blame for the 33 per cent hike in free-market rents. That’s because landlords push for returns to keep pace with the sales market, Mr Inurrieta says. Would-be buyers are also forced into renting by the higher purchase prices.

Spain is a peculiar market within Europe, with one of the highest levels of owner occupancy, and with more than 95 per cent of rental units owned by individuals, rather than institutions.

“It would be a revolution if this worked in Spain,” Mr Inurrieta said of the new regulations. “There is so much under-the-table money here, and so many amateur landlords that don’t have to adhere to any strategic plan with investors.”

Spain’s real estate crash almost a decade ago depressed rents and values, although the attractiveness for investors improved with the turnaround. The average gross return of 4 per cent in 2018, according to Spain’s Development Ministry, compares favorably with the benchmark German bond yielding less than 0 per cent. Spain’s IBEX 35 index ended last year at its lowest annual level since 2012.

Property investors typically expect that as long as there’s population growth, and a relatively free market, home purchases and rentals can beat inflation over the long term - an assertion that will be tested with new rent-cap rules.

Some economists argue that purchase prices have surged so much faster than consumer prices in many developed markets because often the two aren’t structurally linked. For example, home prices, a perennial worry for middle-class urban families, are absent from the consumer basket in many of the world’s consumer price inflation data. Instead, rental costs are typically used.

In Spain, for example, rental housing has just a 3 per cent weighting in consumer inflation, whereas the average family spends about 30 per cent of its income on rent and even more buying a home.

Since Spain’s property crash, banks have rarely financed 100 per cent of a purchase. That’s one factor increasing demand for rentals. So is 35 per cent youth unemployment. Yet, there are many dynamics that are seen across the globe in job-rich cities with scant vacant land.

“This isn’t just Spain, it’s most big markets,” Citigroup’s Mr Lovrics said. “Look at Seattle, which was very affordable years ago, and now it’s just for high net worth.”