How well do America’s consumer protection laws serve people saving for retirement? To get a sense, let’s compare an old car advertisement with a brochure produced by a modern-day insurance company.

The ad (below) for the bare-bones Citroen 2CV, plays with the way sellers of consumer products sometimes make extravagant claims.

Of course the 2CV wasn’t faster than a Ferrari – unless the Ferrari had the brakes on. The prominent explanation makes the ad delightful.

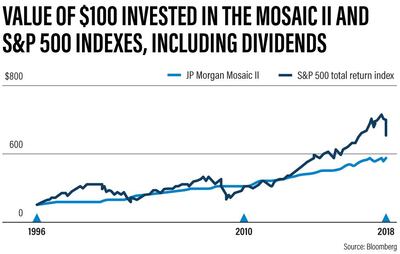

If only one could say the same of today’s ads for retirement products. Consider a brochure promoting the Nationwide Peak annuity, which offers returns tied to a stock index called the JP Morgan Mozaic II. It contains a chart comparing the performance of the Mozaic II to the better-known S&P 500, in which people can invest through simple and inexpensive mutual funds.

Much like the 2CV, the Mozaic II manages to edge out its competitor. This suggests that the annuity could have delivered a return slightly better than the S&P 500, but without the latter’s volatile swings. No wonder the insurer Nationwide has sold so many annuities like the Peak.

Unfortunately, the brochure omits an important fact: like the Ferrari, the S&P 500 isn’t travelling at full speed. The chart calculates returns based on the price of the S&P 500 alone, and excludes the dividends that anyone who invested in the S&P 500 would receive.

Between 1996 and 2018, $100 (Dh367) invested in the S&P 500 plus reinvested dividends could have returned retirement savers almost $1,000 more than the proprietary index. Run the chart into 2019, and the S&P 500 beats the Mozaic II by even more.

Granted, the Nationwide annuity may offer other advantages, such as tax deferral or longevity insurance. A spokesman for Nationwide said that the brochure was meant to demonstrate “consistent, smooth returns when compared to the volatility of the S&P 500 Price Index – not to compare the growth of the two indices,” and that Nationwide chose what it calls the “S&P 500 Price Index” for the chart because “it is available as an investment selection in Nationwide fixed indexed annuities".

But if Nationwide’s goal was to help consumers compare the volatility of the products it offers, its chart arguably fails again. That’s because an S&P 500 linked annuity should be less volatile than the S&P 500, thanks to the formulae the insurer uses to determine returns. So again, the comparison of an engineered, proprietary index to a raw S&P 500 price chart does not provide all the facts needed to make a good decision.

Nationwide isn’t alone: insurers selling annuities commonly omit information that could make competing investment vehicles look stronger. Global Atlantic and AIG, for example, both employ comparisons to the S&P 500 without including or mentioning dividends. Global Atlantic declined to comment, and AIG did not respond to questions.

Many states have outlawed incomplete or potentially confusing marketing materials, yet state regulators grant financial firms significant leeway in determining which facts retirement savers need to see. Meanwhile, at the federal level, the Trump administration has abandoned the “fiduciary duty rule,” which would have curtailed the sale of certain retirement products that weren’t in savers’ “best interest,” and would have required some financial advisers to show their clients potentially better investment options.

I see two simple solutions. First, revive the fiduciary rule, so that more advisers are required to show savers the best products based on historic returns, and not just the products they are most incentivised to sell. Second, put the burden of proof on the seller to demonstrate that marketing illustrations give a complete and fair picture of competing investment options – including simple stock and bond index fund portfolios.

To be fair, tougher marketing and selling requirements could crimp financial innovation and limit investor choice. But given the importance of the decisions involved, and given how many people are already likely to fall short in retirement, it would be prudent to err on the side of caution. Otherwise, millions of Americans may be lured into paying the investment equivalent of Ferrari-like prices, when simpler products could get them further toward their goals.

Ethan Schwartz, an investment manager and financial services executive for 21 years, was a special assistant to the deputy secretary of the Treasury in the Clinton administration

* Bloomberg