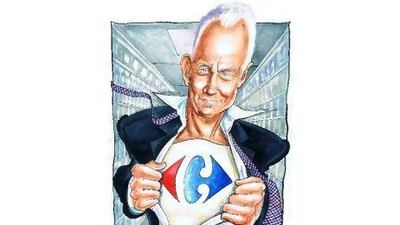

A Lars Olofsson arrived at Carrefour much like a manager joining a football club owned by an impatient and demanding billionaire.

Q&A: Carrefour

When was Carrefour founded? The first Carrefour store opened in 1959 in France by Marcel Fournier, Denis Defforey and Jacques Defforey.

How wide is Carrefour's reach today? The Carrefour group has more than 9,500 stores in 32 countries, through franchises or company-operated businesses.

When did Carrefour set up in the Middle East? Carrefour was the first foreign supermarket to enter the UAE in 1995 in a joint venture with Majid Al Futtaim. MAF owns 75 per cent of the company and Carrefour 25 per cent. While the population of Dubai was only 689,000 people at the time, the company saw an opportunity as the population was growing at 12.5 per cent.

How many stores does the company have now in the region? MAF Carrefour has 37 stores across the Middle East, operating in 11 countries, and claims to be expanding further. It also has 16 Carrefour Market convenience stores.

His predecessor was an Iberian young gun called Jose, not Mourinho of Chelsea and Real Madrid fame, but Jose Luis Duran, who was given just three years to turn around the ailing French hypermarket giant before he was given the boot.

"We face daunting challenges and it's time for us to confront these challenges if we want to regain our leadership position and conquer, or re-conquer, the hearts of all our customers," Mr Olofsson said at his first presentation to industry analysts and investors as the French hypermarket chain's chief executive.

Carrefour's biggest shareholders had become tired of Mr Luis Duran's slow progress and went searching for new management at Europe's big retail and consumer goods companies, eventually hiring one of Nestle's star strategists, Mr Olofsson, a Swedish national.

He came from a trio of management talent at Nestle, who were all tipped as possible contenders for the top job at the Swiss food conglomerate.

Of the two others, Paul Bulcke became the chief executive at Nestle, and Paul Polman took the top job at another multinational, Unilever.

In a bid to prove he was "the special one", Mr Olofsson started his role at Carrefour in 2009 with talk about change and embarking on a transformational strategy.

Industry insiders describe him as open and honest, with enough charisma to take on the high-profile role.

With all eyes on Mr Olofsson, his early performance needed to be spot on because Bernard Arnault, Europe's richest person and the boss of the luxury goods group, LVMH, keeps a close eye on his investment in Carrefour.

He and Colony Capital, a property-investment company, jointly own 14 per cent of Carrefour's shares and 20 per cent of its voting rights, predominantly through a vehicle called Blue Capital.

Having bought into Carrefour at the height of the market in 2007 and paid €50 per share, Blue Capital is sitting on massive paper losses. The shares now trade at €19.50 and Blue Capital is trying its utmost to help management improve the price.

So Mr Olofsson, 59, has to manage the expectations of some powerful owners. He looks to be doing so by going for big changes. But so far, they have had little positive effect on the share price or the bottom line.

The stock has fallen 35 per cent this year and the company has indicated it will announce a 23 per cent fall in first-half profits when it reports at the end of this month.

Like fans tired of the constant unsettled nature of their football team, analysts have become weary of false dawns and few are confident in Mr Olofsson's ability to make revolutionary changes and please the demanding owners.

"There have been so many unsuccessful attempts to revamp the business in the last 10 years," says Andrew Porteous, an analyst at Evolution Securities. "While Carrefour plan to implement a turnaround plan, the risk of this being unsuccessful is high."

Mr Olofsson has a three-year plan, which aims to overhaul the weak French business, offer continuously low prices and expand the group's foothold in emerging markets, including the Middle East where the joint venture with Majid Al Futtaimis expanding stores.

The chief executive has a penchant for sales and marketing lines such as "Welcome to our Planet", his introductory line to a speech about his revolutionary new store concept "Carrefour Planet".

"For me leadership means being able to do more than others and doing things first, before the others," Mr Olofsson explained when he started his role. "And for our customers leadership is about building a bond that makes all the difference between a brand, a great brand and a preferred brand."

He plans to spend €1.5 billion (Dh7.95bn) to refurbish and redesign 500 hypermarkets around the world within two years.

Knight Vinke, activist investors with a 1.5 per cent share of Carrefour's equity, said last April the revamp strategy was the "last chance" and the plan could not "be allowed to fail under any circumstances".

By offering competitive low prices, Mr Olofsson had begun to take market share in its French business last year. In addition, Carrefour and Majid Al Futtaim had also taken market share in the UAE last year and remained the top retailer in the country, according to Euromonitor International.

"The very encouraging results we are seeing from Carrefour Planet, our new hypermarket concept, and the continued execution of our transformation plan, underpin our confidence that we are on track to achieve our goals," Mr Olofsson said in May.

But this year has been somewhat of a nightmare for Mr Olofsson, who has been called both weak and ruthless in a matter of months.

His management team has changed so frequently that Mr Olofsson seems to be taking the industry term - fast-moving consumer goods - too seriously. After rumours of tensions between Mr Olofsson and his chief financial officer, Pierre Bouchut, the Frenchman moved this month to head the growth markets division. Mr Bouchut may have suffered the consequences of four profit warnings announced in less than a year.

Analysts say Mr Olofsson is pushing a performance-oriented culture at the company because the major shareholders expect to see growth in the share price.

This means time in office is short for senior management. Two senior managers who had been drafted in to help to lead the company's turnaround, James McCann and Vincent Trius, also left this year after short terms.

Mr McCann was head of the company's French unit and left in May after being deemed to have performed poorly in little more than a year at the company. His departure came less than three months after Mr Trius left his post as head of Carrefour's Europe division.

Despite displaying decisive action with his employees, Mr Olofsson has been told by Knight Vinke to regain some credibility by resisting pressure from Carrefour's biggest shareholders, Blue Capital and Mr Arnault.

The chief executive is being boxed in from shareholders on all sides. Numerous strategic changes have either hit walls or been slated by minority investors. A merger of Carrefour's Brazilian operations with the local market leader, Pao de Acucar, was canned after Casino, a major shareholder in the Brazilian group and a rival to Carrefour in France, objected to the deal.

Hastening to put together some kind of solution, Mr Olofsson is believed to have flown to Brazil this week to meet Walmart executives to sell Carrefour's Brazilian business to the big US retailer. Divisions over the direction of the business are reported to have left the chief executive captaining a near mutinous management.

A botched idea to spin off much of the property that the business owns has also received criticism for pandering to shareholders.

"By implementing Carrefour Property's strategy in France, Spain and Italy, Carrefour will get the full benefit of more focused management of its property portfolio to go hand in hand with the roll-out of Carrefour Planet," Mr Olofsson said in May before he performed a U-turn only weeks later.

Industry analysts say Mr Olofsson is in a difficult position.

Economic factors and austerity measures in much of Europe are likely to mean the European business does not hit sales figures originally projected, while results at the end of the month are forecast to disappoint.

Just like the football managers at Europe's top clubs, the pressure is now on Mr Olofsson to bring in new players to revive his team, as well as rethink his game plan.