Police in India stormed Twitter’s office in New Delhi last month and among them were officials from a special cell that normally investigates crimes such as terrorism.

The reason for the raid: a decision by the microblogging site to label a tweet by the spokesman of the country’s ruling party as “manipulated media”.

The incident is considered to be a flashpoint in increasingly tense relations between US social media companies and authorities in the second-biggest internet market.

The raid came before new information technology rules for social media companies came into effect at the end of May. The rules were introduced in February, triggering privacy and data control concerns.

Under the new framework, large social media companies – both foreign and local – are required to appoint compliance executives to co-ordinate with law enforcement officials, set up mechanism to address grievances and remove content within 36 hours if they receive a legal order to do so.

They also must disclose the “first originator of information” if authorities demand it.

“Social media platforms will initially have a tough time complying with the new IT rules,” says Ashok Kadsur, co-founder of SignDesk, an IT company in Bengaluru.

“These rules will require social media giants to pour more resources into regional operations and create an efficient system to streamline the massive number of grievances that will undoubtedly be coming their way.”

The stakes are enormously high. With a large and young population, India is a lucrative market for global social media companies, which have invested heavily in the country.

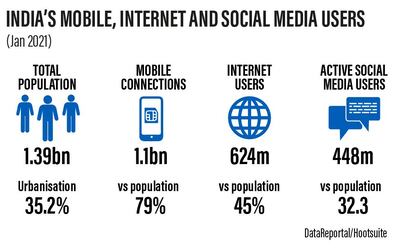

The country had about 448 million social media users as of January this year, up by 21 per cent on annual basis, according to figures published by DataReportal and Hootsuite.

Capturing market share in India is also essential for companies such as Google and Facebook, as growth in the US and Europe plateaus.

“In the past, social media giants could have pushed back against these new rules,” says Mr Kadsur.

“However, with markets in Europe and the US slowly reaching saturation, platforms such as Twitter, Facebook and Instagram are now placing all their eggs in India’s basket.”

The issues social media companies face in India are part of a much broader battle between big technology companies and authorities in other parts of the world.

A global debate is raging on ways to enforce regulatory controls without jeopardising privacy and freedom of speech in democratic countries.

The government cited the need to maintain “law and order and national security” as a key factor behind the new rules.

However, companies are concerned that the rules could compromise data privacy and curtail freedom of expression.

Facebook-owned WhatsApp – which has 400 million users in India, its biggest market – has filed a lawsuit against the Modi administration.

However, pressure is mounting on these companies and Twitter has already come under fire from the government over its delayed compliance.

The government told Twitter this month that it was being given a final chance to comply or face “unintended consequences”, Reuters reported, quoting an official letter.

With about 17.5 million users, India has Twitter’s third-largest user base worldwide, after the US and Japan.

Twitter told The National that it "remains deeply committed to India" and has assured the government that it "is making every effort to comply with the new guidelines and an overview on our progress has been duly shared".

The company says it will continue its “constructive dialogue with the Indian government”.

Industry insiders say social media companies will eventually have to fall in line.

“India’s a very crucial market for these companies,” says Mehar Gulati, founder of public relations and social media agency Scarlet Relations.

“The companies will have no choice but to comply with the regulations if they wish to continue their operations.”

However, legal experts say Indian government rules are in conflict with privacy guidelines of social media companies.

“This is the main issue between the government and the companies, as an argument of infringement of access to privacy is being made,” says Ashutosh Shekhar Paarcha, a Supreme Court advocate.

“The underlying issue is that [some of] these companies have already boasted to their users about their privacy ... and how they provide end-to-end encryption.”

The companies fear a major reduction in users if they comply with the new rules, he says.

WhatsApp has long assured users that its app is “end-to-end encrypted”, which means they can communicate without their messages being stored or visible to others.

This is a major draw for those who are increasingly becoming concerned about privacy.

However, the messaging app “does not have a great case [in court]” and the best option might be “back door conversations with the government to try to reach consensus”, says Mr Paarcha.

WhatsApp’s parent company Facebook said last month that it intends to “comply with the provisions of the IT rules and continue to discuss a few of the issues, which need more engagement with the government.

Pursuant to the IT rules, we are working to implement operational processes and improve efficiencies”.

The social media company stressed that it “remains committed to people’s ability to freely and safely express themselves on our platform”.

There has been some underlying tension between the Indian government and social media companies in the past over content posted on these platforms.

Last month, they were ordered to take down posts that criticised the Indian government’s response to the coronavirus pandemic amid a deadly second wave of infections. The companies complied with the request in the Indian market.

In a separate incident in February, Twitter refused to block some accounts that criticised India’s controversial farm reforms.

However, if social media companies do not comply with the new rules, “the likely consequences could vary on a spectrum from mere fines being levied to the other extreme that they may be banned in India”, says Mr Paarcha.

Local employees also face the risk of imprisonment if their companies do not follow the new code.

The government has already proved that it is willing to take strict measures, says Mr Paarcha. Chinese video-sharing app TikTok, which was immensely popular in India, was banned last year amid border tensions with China.

Industry experts say the best course of action for India’s social media companies is to push for the Modi administration to relax the rules.

“It is important to come to a mutual agreement which benefits the government ... [and is also] in public interest,” says Husain Habib, co-founder and chief marketing officer at Hats-Off Digital, a digital media marketing agency.

“If it is a fair deal for both; the companies themselves will abide by the regulations imposed.”

However, the issue is complex and there is unlikely to be a quick fix.

While the authorities are “only doing their job”, they are also taking away the user’s right to privacy and trying to dictate terms in the world’s largest democracy, says Mr Habib.