Sachin Kharvi, who sells fruits and vegetables in a bustling market in India’s financial capital Mumbai, only accepted cash for his products until four months ago.

But as the coronavirus pandemic spread across the length and the breadth of the country, Mr Kharvi and other vendors in the market were forced to roll out mobile payments options as customers shied away from cash due to safety concerns.

“Now, 50 per cent of my customers are using mobile payment apps like Google Pay and Paytm,” he says.

India's digital payments sector was booming long before the pandemic. Mobile payments alone registered a 163 per cent growth to $286 billion in 2019 compared to the previous year, according to an S&P Global report.

It is a sector that companies are keen to tap and the competition is heating up as international players look to get a slice of the booming payments market in Asia's third-largest economy.

WhatsApp this month became the latest entrant to India's flourishing payment industry. It will take on the three largest companies in the space: Google Pay, Walmart-owned PhonePe, and Paytm, which is backed by Softbank and Alibaba.

“WhatsApp is definitely going to be a big disruptor in this space,” says Utkarsh Sinha, the managing director of Bexley Advisors, a Mumbai-based advisory firm that works with technology companies. “Few companies have the might that WhatsApp does to upend the market.”

The Facebook-owned messaging app aims to capitalise on its large user base of some 400 million people in India, which is its largest market.

WhatsApp users are already on the app multiple times a day and that is a significant advantage it has over the competition, Mr Sinha says.

“I would be very surprised if [WhatsApp] does not become the number one or number two [player] in the next couple of years,” he says.

Google Pay is currently the most popular app for mobile payments, with some 75 million active users in India on its platform transacting in May. PhonePe had 60 million users and one-time market leader Paytm, had 30 million in the same month, according to a report by Bernstein.

Underpinned by rising smartphone ownership along with lower handset and data costs, the sector is primed for further growth .

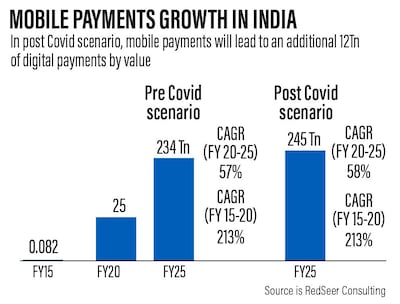

A report published in September by RedSeer Consulting projects mobile payments in India to grow 58 per cent annually to reach 245 trillion rupees ($3.3tn) by 2025.

The Covid-19 outbreak is giving an additional 5 per cent boost to these projections, according to the report.

“Consumers are now pushing this because they're safety conscious and they're reaching out to retailers to accept digital payments,” says Anand Kumar Bajaj, managing director and chief executive at PayNearby, which partners with small local stores to facilitate their use of digital financial services. “The pandemic is a key driver.”

Mobile payments “are catching on like wildfire”, says Mr Sinha. “And it's not just [at] the top of the pyramid; it's [at] the bottom of the pyramid too.”

Digital payments are also being propelled further by Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government that has pushed to turn its largely cash-based economy cashless. India's widely-publicised demonetisation move in 2016, when the two highest value banknotes were banned overnight in a crackdown on hoarding of illegal cash, was also part of the country's efforts to develop digital payments.

“I would say a push from the government and the banking regulator towards greater digital payments adoption is working,” says Nitish Asthana, president and chief operating officer at Pine Labs, a platform for retailers in India, providing transaction technology and financing. “While India still is a cash-dominant economy, the mind-sets are gradually changing. ”

He says that “India’s rising and aspirational middle class with increasing household income is ready to experiment with digital modes ... and add to that the young demographics which is internet savvy ... and the environment is ripe”.

As a result, Mr Asthana says “the market is huge and there is room for everyone”.

“WhatsApp will [also] be a big [game] changer, especially in smaller towns where WhatsApp is already well-known for most of the population,” says Mandar Agashe, the founder and managing director of Sarvatra Technologies.

“We have not even scratched the surface of the markets and we already talking about numbers in billions of transactions,” he says.

But there are some restrictions on the pace at which WhatsApp – which started testing its service in India in 2018 – will be able to grow.

The National Payments Corporation of India has limited the company to 20 million users initially and WhatsApp will only be allowed to expand gradually.

Mr Agashe at Sarvatra Technologies says these restrictions give the ecosystem time “to be ready for a sudden surge in transactions”.

Payment services including Google Pay and WhatsApp operate on the Unified Payments Interface, or UPI, developed by the Indian government. This means that the platforms have to be linked to a bank account and debit card, and instant money transfers are made bank to bank, as opposed to the money being moved to and held in a separate digital wallet.

The National Payments Corporation of India, which controls UPI transactions, on November 5 – the same day WhatsApp's roll out was announced – said that each third-party app could only handle up to a 30 per cent share of the total UPI transaction volumes. This cap comes into effect from the beginning of 2021, but companies already operating in the market will have two years to comply with the rule.

Google Pay, currently the market leader, has hit out against the move. “A choice-based and open model is key to drive this momentum,” Sajith Sivanandan, the business head at Google Pay, India, said in a statement in reaction to the government measure. “This announcement has come as a surprise and has implications for millions who use UPI for their daily payments and could impact the further adoption of UPI and the end goal of financial inclusion.”

But industry insiders say it will help in preventing a monopoly in the market.

“It's to help citizens or there could be monopolistic moves which could swing the pricing, so I think the intent of the cap is not bad,” says Mr Bajaj.

With several companies operating in the sector, industry insiders say market leaders will emerge eventually.

“While it's a crowded space, competition is always good from a consumer innovation perspective,” says Ashwin Sivakumar, the co-founder and chief of digital business growth at JugularSocial Group.

“We are now likely to see more innovation and even more integrated value propositions from all the players in this space. We might end up seeing some market consolidation and emergence of a couple of clear leaders in this space.”

Meanwhile for WhatsApp – which is largely used by individuals – getting businesses on board to use its payments service could be the key to eventual monetisation, analysts say.

Some of the groundwork towards this has already been laid.

This year, Facebook invested $5.7bn for a 10 per cent stake in Jio, a technology platform controlled by Asia's richest man, Mukesh Ambani. Jio is taking on the likes of Amazon as it vies for a chunk of the e-commerce market in India. WhatsApp is likely to play a significant role in the fight for dominance with its payment service, having already tied up for an online booking service with JioMart that facilitates purchases and delivers groceries from local stores.

All the elements are in place for WhatsApp Pay to succeed in India, financial technology experts say.

“It's a question of whether WhatsApp ends up unseating Google Pay as the largest player in India,” says Mr Sinha.