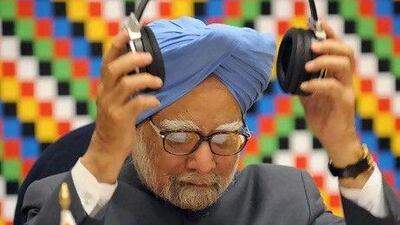

When Manmohan Singh, the Indian prime minister, arrived in Africa this week, he would have seen plenty to remind him of home. Tata and Mahindra buses clog the roads, while Bharti Airtel billboards bring a dash of colour to city skylines.

Mr Singh arrived in Ethiopia on Monday for the second India Africa Forum Summit - which he hopes will confirm India's earnestness to become part of the expanding scramble to secure Africa's riches.

In 2000, India did barely US$10 billion (Dh36.73bn) of business a year with Africa. Last year, trade between the two sides reached $46bn, and it is hoped this will grow to $70bn in the next three years.

"Africa is emerging as a new growth pole of the world, while India is on a path of sustained and rapid economic development," Mr Singh said before departing for his visit.

India has been slow to move into Africa - particularly when the inevitable comparison is made with China's fast-moving expansion from the Cape to Cairo. And although India has been at pains to insist it is not trying to compete with its Asian rival for African business, the two will keep a wary eye on each other as they pursue lucrative oil, gas and other natural resource contracts.

For India, though, the payoff is more than just access to what is under the earth. Africans are becoming significant buyers of Indian goods including motorbikes, tyres and pharmaceuticals. Ranbaxy, Cipla and Dr Reddy's, Indian makers of generic medicine - drugs whose patents have expired - are the biggest suppliers of HIV remedies on the continent.

Partly thanks to Africa, India's makers of generic drugs have risen from insignificance to become the second-largest by volume producers in the world. Africa now consumes almost 15 per cent of India's total drug production. For Africans, drugs that once cost $10,000 a year are now available for under $400.

Perhaps with a view to distinguishing itself from China, which has invested heavily in mining and physical infrastructure, India has emphasised communications and skills training. It has set up a diamond finishing institute in Botswana and an IT institute in Ghana.

And, like China, India is also bringing cash. Lots of it. Mr Singh told the summit that India would extend $5bn of loans to various African countries. This is in addition to the $5.4bn extended at the last summit three years ago.

"Africa possesses all the prerequisites to become a major growth pole of the world in the 21st century. We will work with Africa to enable it to realise this potential," Mr Singh told the forum.

For the continent, this provides yet another alternative to traditional sources of funding, such as the World Bank and western donors. As with China, which has also extended significant soft loans to African countries, Indian money comes with few strings attached.

"I am sure the role of the World Bank will also become irrelevant in the coming days," Katureebee Tayebwa, a counsellor at the Ugandan High Commission in New Delhi, told India's Indo-Asian News Service last week. "The World Bank gives us money but imposes so many conditions. We do not want conditions, we want money."

Perhaps India's biggest achievement is integrating itself into the fabric of African life. By some counts, 2 million Indians live on the continent, many of whose families have called it home for generations.

And more recent arrivals are also establishing themselves in a way that suggests permanence. The drug maker Cipla, for example, is listed on the Johannesburg Securities Exchange. So is the Indian steel maker ArcelorMittal.

Bharti's $9bn deal to acquire mobile phone operations in 15 African countries last year is the biggest investment in Africa so far by an Indian company. More such deals are expected as Indian companies acquire assets across the continent.

There will, of course, be stumbling blocks. India's investment is largely private-led. African countries are increasingly insistent that local shareholders be given a stake in investments. ArcelorMittal, for example, was obliged to sell a 26 per cent stake in its South African holdings to local stakeholders to comply with regulations on black ownership.

But such issues are unlikely to put off Indian investors. Africa's average growth of 5 per cent over the past 10 years, and its insatiable appetite for technology, medicine and infrastructure, will continue for many years.

Mr Singh's six-day visit to Africa will therefore end on a happy note - better than the conclusion of the 2008 summit, which was by all accounts poorly attended. This time, India's intentions are being taken more seriously.