Rebecca Bundhun, Foreign Correspondent, reports from Mumbai

India’s burgeoning civil nuclear power ambitions are creating more opportunities for domestic and foreign businesses, despite the huge challenges the sector faces.

India has made significant progress in its nuclear power programme recently as it strives to meet the growing appetite for power.

Canada on Wednesday announced a C$350 million (Dh1.04 billion) deal to supply uranium to India. Canada’s Cameco, one of the world’s biggest producers of uranium, is set to provide 7.1 million pounds of the fuel to India over the next five years.

Canada had previously banned uranium exports to India after it used Canadian technology to develop a nuclear bomb in the 1950s. India is also close to reaching a civil nuclear agreement with Australia over uranium fuel supply.

A few days earlier, the Nuclear Power Corporation of India (NPCIL) signed an agreement with Areva, a French firm, related to the Jaitapur nuclear power plant in Maharashtra, which has suffered setbacks over issues including pricing of the project and liability laws. This is a significant step in allowing the project to move forward. Areva also signed a deal with the Indian engineering company Larsen & Toubro (L&T), which would lead to some of the key nuclear equipment for the plant being manufactured locally.

“This partnership will add new dimensions to the capabilities of India’s manufacturing sector in the nuclear business,” said MV Kotwal, the director and president of heavy engineering at L&T.

In January, the Indian prime minister Narendra Modi reached a breakthrough deal with the US president Barack Obama to pave the way for more investment into nuclear energy.

These developments come despite strong opposition among many to the development of India’s nuclear power capabilities, largely because of concerns over safety.

India’s demand for energy is rapidly rising amid a growing economy and urbanisation, meaning it needs to boost production capabilities to improve its energy security.

There is already a shortage of power. Many parts of the county suffer frequent blackouts and about 300 million people do not have access to electricity, according to the World Bank.

Coal is the country’s biggest source of power, accounting for about two-thirds of its electricity production. Despite expansive natural reserves of coal, the country is heavily dependent on costly imports of the fuel.

The need for energy is only expected to surge over the coming years, and nuclear power is considered by authorities to be part of the solution to the problems.

To this end, Mr Modi has urged the department of atomic energy to triple nuclear power capacity by 2024 from 5,780 megawatts. India is aiming for nuclear power to produce 25 per cent of its electricity by 2050.

“India’s dependence on imported energy resources and the inconsistent reform of the energy sector are challenges to satisfying rising demand,” says the World Nuclear Association. “India’s fuel situation, with a shortage of fossil fuels, is driving the nuclear investment for electricity.”

But it adds that the nuclear targets would require “substantial uranium imports”.

Trade bans have held back the industry, restricting imports of uranium. This has led to a “largely indigenous” development of the industry.

“India’s nuclear energy self-sufficiency extended from uranium exploration and mining through fuel fabrication, heavy water production, reactor design and construction, to reprocessing and waste management,” the World Nuclear Association says.

“Because of earlier trade bans and the lack of indigenous uranium, India has uniquely been developing a nuclear fuel cycle to exploit its reserves of thorium. Since 2010, a fundamental incompatibility between India’s civil liability law and international conventions limits foreign technology provision. India has a vision of becoming a world leader in nuclear technology because of its expertise in fast reactors and thorium fuel cycle.”

Thorium is beneficial for India because it has substantial resources of the fuel. It is also potentially safer. Uranium is fissile on its own, whereas thorium is not, meaning thorium’s reactions can be better controlled and stopped where necessary, and therefore it is less likely to result in a nuclear reactor disaster on the scale of Fukushima. Proponents say thorium produces less radioactive waste and more power than uranium. But opponents argue that it still produces waste that is highly hazardous, could still result in accidents and is has yet to be proved commercially viable.

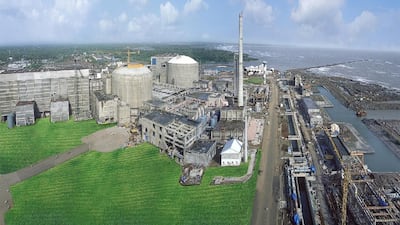

There are seven operational nuclear power plants in India. The first, the Tarapur plant in Maharashtra, became commercially operational in 1969, a two-units facility with a total capacity of 320MW. The latest was the Kudankulam project in Tamil Nadu, which started commercial operations in December with a capacity of 1,000 MW.

In its federal budget presented in February, the government said it would commission the second unit of the Kudankulam nuclear power station, which uses Russian technology, in the 2015-2016 financial year. It is another project that has suffered severe delays, partly because of opposition by locals.

Mr Modi this month called for easing of restrictions on uranium imports to allow India to increase its nuclear power production.

“Nuclear energy is definitely one of the options India has,” says Karl Rose, the senior director of policy and scenarios at the World Energy Council. “If you look at it objectively and not emotionally, it’s very often a question of, ‘Is it cost competitive?’ In many western countries, new nuclear stations are not being built because of cost rather than public sentiment. For India, the question will be, under the current economic environment, can you build nuclear power stations at a low enough cost that the power you produce will be competitive?”

In comparison, the cost of building a nuclear power plant in the United States, excluding financing, is about 30 per cent higher than in India, according to the World Nuclear Association. Delays to projects would add to expenses, however.

It is also critical to try to prevent opposition to projects, he adds.

“If you decide that it’s part of your portfolio, you need to engage the stakeholders early enough that you are able to execute the projects in a timely fashion and you don’t get held up in courts because people protest and challenge the licences.”

Cyient, a technology and engineering company based in Hyderabad that has developed nuclear plant engineering expertise, is among the companies that stand to benefit from development of India’s nuclear power infrastructure.

“The growing demand for energy, combined with the rising need for clean power generation options, has helped nuclear power plants make a big comeback,” says Bharat Heavy Electricals, another nuclear-sector manufacturing company. “Governments across the world have drawn up aggressive plans for nuclear power programmes and have scaled up their investments accordingly. All of these dynamics have contributed to major opportunities opening up within this sector.”

The International Atomic Energy Agency highlights that nuclear energy could play a role in helping to grow India’s developing economy. It also says nuclear energy can help reduce the impact of volatile fossil fuel prices, as well as mollify climate change.

There has been mounting pressure on India from its global peers over its carbon emissions. New Delhi has been rated as the world’s most polluted city and 13 of the world’s dirtiest 20 cities are in India, according to the World Health Organization.

“The world takes a lead on climate change and teaches lessons,” Mr Modi said earlier this month. “But when we tell them we want to proceed on the path of nuclear energy, since it is good for environment protection, and ask for fuel, they refuse.”