Vijay Banka, managing director of a major producer of sugar in India, expects the country's push towards greener forms of energy to boost profitability.

His company, Dwarikesh Sugar Industries, can crush 21,500 tonnes of sugar cane a day in its mills. It also produces ethanol – a fuel that is made from the plant.

“The sector is on the threshold of a change,” says Mr Banka.

India wants ethanol to play a bigger role in its energy mix as it looks to more renewable sources to reduce its dependence on expensive oil imports and cut its carbon footprint.

Earlier this month, Prime Minister Narendra Modi brought forward by five years a deadline to achieve 20 per cent ethanol blending in petrol – from 2030 to 2025.

India currently has an 8.5 per cent blending rate to reduce environmental pollution. Mr Modi described ethanol as "one of the major priorities of 21st century India" in his World Environment Day announcement.

Initiatives such as these are all the more pressing as the country – the world's third-largest carbon emitter – has pledged to reduce emissions as part of its commitment to the Paris Agreement on climate change.

There are also economic factors and energy security concerns at work behind the plans of Asia's third-largest economy to mix more ethanol with petrol.

India imports about 76 per cent of the crude it needs and its dependence on imported oil is expected to rise to 90 per cent by 2030.

Expanding demand could double the country's oil import bill to $181 billion by the end of this decade, according to the International Energy Agency.

“The Indian government’s E20 programme targeting 20 per cent ethanol blending in petrol by 2025 not only propagates a low-carbon economy but is a step towards achieving energy security,” says Manish Dabkara, chairman and chief executive at EnKing International, a company that provides services to mitigate climate change.

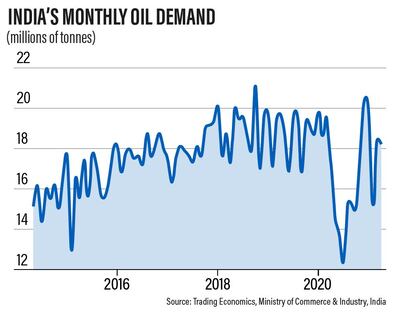

The push to a greener future comes as India has been grappling with a growing demand for oil that has driven the country's petrol and diesel prices to record highs.

EnKing says the increased ethanol blending will help to bring down the country's oil import bill, reduce its carbon footprint and improve the domestic economy by boosting employment and income.

The government estimates that the initiative would reduce India's vehicle fuel import bill by $4bn annually.

The programme will have the added benefit of allowing farmers to earn more money by selling their crops for ethanol production.

Ethanol in India is largely produced through the fermentation of sugar cane or damaged food grains such as wheat and rice.

Suyash Gupta, director general of the Indian Auto LPG Coalition, says ethanol-blended petrol reduces emissions by 20 per cent and India's move to bring its blending targets forward "illustrates the seriousness with which the authorities are taking up the issue".

The move also show “our country’s commitment to reduce greenhouse gas emission by 33 to 35 per cent, relative to 2005 levels, by 2030”, says Arun Kumar Singh, director of marketing and refineries at Bharat Petroleum Corporation, a government-owned oil and gas corporation.

However, the biggest challenge is to ensure that there is sufficient availability of ethanol to meet the target, according to Mr Gupta.

Sugar mills have ramping up production of ethanol with the help of soft loans from the government for distillation infrastructure.

To prevent a possible shortage of sugar in the country as mills use more feedstock for ethanol processing, the government needs to boost sugar cane cultivation in four to five states, says Mr Gupta.

“The sugar cane farmers or the sugar industry, in general, would also need to be incentivised enough to invest sufficiently in biofuel plants and food grain-based distilleries,” he says.

As long as the country manages "to ramp up production of sugar cane and ethanol, along with establishing grain-based distilleries in sufficient number, it is likely that India will achieve its target", he says.

Mr Banka says sugar producers have leapt into action with subsidised loans and the industry has responded in "equal measure".

"We are all trying to increase our ethanol capacity so that we are able to get closer to the 20 per cent blending target.”

Dwarikesh Sugar Industries supplied about 30 million litres of ethanol in the past financial year through to the end of March. It now expects to boost its production to 50 million litres in the current financial year as it pushes for its production target of 100 million litres.

“It will definitely help our profits,” says Mr Banka.

An assured buying price from the government would mean there is a guaranteed margin, which is a significant incentive for producers to invest in ethanol production.

The government's revised targets also work in favour of farmers as mills would be willing to pay even higher rates for their crops, Mr Banka says.

Without the ethanol-blending programme, “there, perhaps, might have been a glut-like situation”, he says.

“The objective [of the government] is to see that the sugar production in the country is more or less equal to consumption and if there is a surplus, there is a small surplus that can be exported easily,” says Mr Banka.

India is the world's second-largest sugar producer after Brazil and is a major exporter. However, it could lose its position with the government's push to meet its ethanol targets.

A report by London-based commodity trader Czarnikow Group forecasts that India's plans for ethanol could reduce the country's production of sugar by more than 6 million tonnes, meaning that it would no longer have a massive sugar surplus and be a major exporter.

The move has implications for other sectors of the economy. The country's car industry will have to make adjustments as the corrosive qualities of ethanol mean rubber and plastic parts in vehicles will have shorter lifespans.

Another question being raised is whether India's plans to move towards electric vehicles would mean that there may ultimately be less demand for fuel, including ethanol. How much commercial sense does it make today to invest in fuels that will eventually be phased out?

New Delhi aims for 30 per cent of private cars and 70 per cent of commercially driven cars to be electric by 2030 across the country.

But industry pundits say that the EV sector is still at a very nascent stage in India, It faces challenges such as a lack of charging infrastructure, hence the need for the country to invest in other environmentally friendly solutions.

“While electric vehicles seem to be a good option, their technological and financial feasibility is still several years away for our country,” says Mr Gupta.

Turning sugar cane into fuel could be a more immediate solution to help address India's pollution problem and its drive to reduce its dependence on oil imports, he says.