This month, one of India's biggest start-ups Paytm, challenged the dominance of global internet giant Google – by launching its own mini app store.

The homegrown FinTech took the ultimate step after it was temporarily removed from Google's Android app store, accused of a policy violation.

“App developers are effectively dependent on a very giant monopoly, namely Google,” Paytm’s founder and chief executive Vijay Shekhar Sharma said during an online conference announcing its "mini app store". He likened Google to “a toll collector”.

Mr Sharma is not the only one feeling the need to stand up to a bigger rival.

More than 95 per cent of smartphones in India use Google's Android operating system, and tech start-ups have been angered by the internet company's plans to charge a 30 per cent commission on purchases made in its app system, which was due to come into effect this month.

In reaction, dozens of Indian start-ups are banding together to set up a collective to lobby against the dominance of Big Tech. In at least a temporary victory for these firms, Google has delayed its deadline by six months for Indian companies to comply with its new billing policy.

In a statement on October 5, the search engine giant said it was “mindful of local needs and concerns” and subsequently it had decided to set up “listening sessions with leading Indian start-ups to understand their concerns more deeply”.

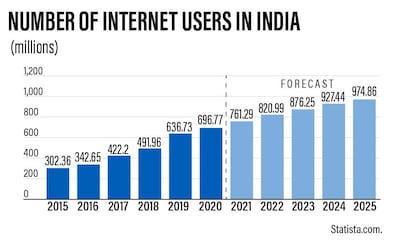

The tussle between local start-ups and digital giants comes as the country of 1.3 billion people offers a lucrative opportunity for companies targeting its large, growing base of internet users.

Analysts say that local start-ups, backed up global investors, are in a strong position to fight back.

“India as a country has long used western civilisation as a frame of reference,” says Suraj Ravi, the founder of Mumbai-based technology star-tup QWR. “But when it comes to being a digital society, we're actually giving them a tough fight.

“We have enough technology that take away the entire requirement of a middleman. We need to have our own system that is run by us, with an Indian solution.”

Nikhil Kamath, the co-founder and chief investment officer of asset management firm True Beacon and FinTech fund and incubator Rainmatter, says India was long seen as a back office for the world's IT needs. However, “since 2010, the prominence of Indian tech companies which aim to create consumer-centric products like Paytm, Flipkart, Zomato is on the rise”, he explains. “They are competing with multinational companies in the largest consumer market.”

Bangalore-based Flipkart is one of the major success stories out of India that took on a global giant. Like its American rival Amazon, it started out as an online bookseller and was launched by two young Indian entrepreneurs Binny Bansal and Sachin Bansal in 2007. The company, which was set up out of an apartment in Bangalore with just a few thousand dollars, went from strength to strength to compete as an alternative online marketplace to Amazon.

In 2018, Walmart acquired a 77 per cent stake in Flipkart for $16bn. As of 2019, Flipkart was the largest online retailer in India, with a market share of 31.9 per cent, ahead of Amazon's 31.2 per cent share, according to data from market research firm Forrester.

“In any consumer segment, a company which can be transparent, customer aligned and make lives easier will definitely succeed,” says Mr Kamath.

This is true of the ride-hailing app Ola. Also emerging out of Bangalore – a city in south India often described as the country's answer to Silicon Valley – Ola has gone head-to-head with Uber. The two rivals claim they have the lead in India’s ride hailing market. Uber said in February that it had more than 50 per cent market share, while Softbank-backed Ola said at the time that it was the largest platform, with more than 200 million customers.

However, experts point out that most major start-ups in India are inspired by their Silicon Valley rivals, raising concerns about innovation.

“In some ways, that can prove to be a hindrance,” says Utkarsh Sinha, the managing director of Bexley Advisors, a Mumbai-based advisory firm that supports tech and media companies and investors in early funding rounds. “However, paradoxically I feel that has been good for India. The growth of global platforms in India helped seed the community of creators that are going on to generate 'unicorns' [start-ups with $1bn plus valuations] today. The presence of Silicon Valley giants in India has served as the nucleus to create Indian innovators.”

Praveen Tyagi, the founder of Indian education technology start-up STEP app, says: “Global companies have offered a base for growing individuals and Indian companies to come forward and explore these opportunities for growth and success.”

Many have seen immense success as well. Paytm, for example, has managed to fend off competition from Google Pay to become the largest operator in the 2,000tn rupee digital payments space in India, according to a report released in August by consultancy RedSeer. The FinTech has nearly 50 per cent of the local payment market share while Google Pay commands just 10 per cent, the report says.

RedSeer explains that Paytm's extensive growth has been helped by its presence in India's small towns as well as big cities, which has allowed it to add millions of shopkeepers to its platform.

"Paytm has the highest top-of-mind recall and unaided awareness among merchants,” according to RedSeer. It is the “most used app” among the merchants, with 68 per cent of those cited in RedSeer’s study using Paytm to accept payments.

Like all of India's major tech start-ups, Paytm has attracted substantial funding from abroad to help fuel its growth and it is backed by investors including Softbank, Berkshire Hathaway, and Ant Financial.

“These are not small start-ups – they have huge investments from [foreign] private equity investors,” says N Raja Sujith, the partner and south India head of law firm Majmudar and Partners.

He explains that if companies like Paytm lobby against Big Tech, the government will have to listen to them.

But Google is also an important investor in India's tech space, having committed to inject $10 billion into the sector over the next five to seven years. This includes its investment of $4.5bn in July into Indian conglomerate Reliance Industries' digital arm, Jio Platforms, for a 7.73 per cent stake. Facebook has invested in Jio Platforms also.

India's tech and Big Tech are heavily intertwined and this is why, Mr Sujith explains, the government and the major players are likely to want to “find a middle path solution” to the current dispute that has flared up over Google's new app billing system.

“In certain areas, like Google and Apple apps store, you don't have a competitor at all,” says Mr Sujith. “There is a real dominance due to their technological advancement.”

Paytm’s mini-app store is no comparison to Google’s mammoth app store, according to experts. But the fact that a local start-up ventured to challenge a competitor with their own home-grown alternative shows how Indian tech start-ups are challenging their bigger rivals.