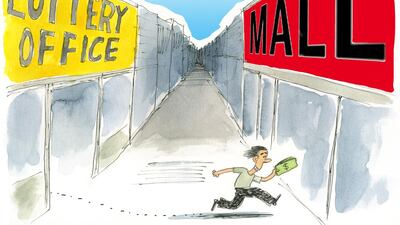

I turned on the car radio just in time to hear a listener being congratulated for winning the day's cash prize. The two presenters talked about what they would do with the money if they had won it - they were going to spend it on themselves. "After all, it's money that didn't exist in your life before now." "Enjoy it." "Blow it on something special." The winner already had plans and needed no encouragement to be frivolous.

A friend recently came into a lump sum that she did not expect. She has squirrelled it away in an investment that she does not really understand, but that promises great returns. Her logic? "This is bonus money. And I don't need it to live on."

The first person is going to use their winnings on something they don't need, and the second is taking a big risk.

This got me thinking. Money is money, isn't it? Dh1,000 is still a thousand whether we win it or work for it.

No. Not really - not according to how we allocate it and account for it mentally. The value of a dirham depends on how the dirham comes into our lives.

If it is cash in lieu of a birthday gift, a windfall or just found lying on the ground, we justify taking on massive risk or squandering it.

This experiment shows us what we tend to do:

Richard Thaler, a behavioural economist and the co-author of the book Nudge, divided a group of students into two. Group A were told they had won US$30 each. They could choose to take part in a coin toss that would win them another $9 or lose them $9, depending on which side the coin landed on.

This type of situation is called a two-stage version - the $30 is presented separately from the gamble.

Group B won nothing but were told they could choose between getting $30 on the spot, or taking part in a coin-toss that would give them $9 less if it landed on heads, or $9 more if they got tails. In other words, they have exactly the same possible outcome as group A, but the setting is framed differently - it's a one-stage version. This is how it was put to them: Choose between a sure gain of $30 or a 50 per cent chance to win $39 and a 50 per cent chance to win $21.

Which group do you think were the bigger risk-takers? Group A, which already had winnings of $30 in hand, or group B, which had been given nothing and had to choose an option?

If you follow the logic of the examples I started with, then you wouldn't be surprised to learn that 70 per cent of the first group took the greater risk. Contrast this with the 43 per cent who took on the gamble in the second group instead of just keeping the $30. The first group justified it by thinking of the $30 as bonus money and were willing to lose their winnings because it's not theirs anyway - not really.

It is a prime example of mental accounting that differentiates between money we win and money we earn, even though $30 is still $30.

Here's a simple example - you win money in a game. You then go on to lose what you won. You shrug your shoulders and say "win some, lose some". Again, it wasn't really your money - it was what you had won, so it's not so painful to lose.

The way we justify the loss is called the house money effect. It comes from the casino term "playing with the house's money", and in a nutshell it refers to investors taking greater risks when investing with profits, or money that we are somehow gifted. Gambling houses know the result of this effect all too well and thrive on it, as do marketing folk. This is why we are bombarded with free air miles, phone calls or credit card points. The reality is that nothing is free - but if we think it is, we, on average, end up spending more that we saved, won or were gifted.

The head of a company that issues coupons and two-for-one deals told me once that this is why they are so successful - not because people save, but because the outlets make so much more out of people who use the offers.

People who use coupons end up spending more at the outlets, on average, than people who don't have special deals.

We will always find ways of making painful situations hurt less, but when it comes to money a dirham is a dirham no matter how it comes into your life. So hold on to it and make it part of your budget, not your bonus.

Nima Abu Wardeh is the founder of the personal finance website cashy.me. You can reach her at nima@cashy.me.

Follow us on Twitter @TheNationalPF

Even a bonus should not be squandered

A dirham is a dirham no matter how it comes into your life, so don't take unecessary risk with it and fritter it away, writes Nima Abu Wardeh.

Most popular today