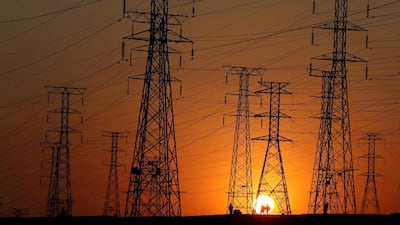

Another punishing round of power cuts has pushed many South Africans to seek alternatives, spurring businesses and entire towns to adopt wind, solar and other sources of energy.

The country’s largest retail chain Shoprite Checkers said it now has solar panels installed on its rooftops that can produce 1,200 megawatts of electricity – enough to power a small town.

“So far, we have installed solar photovoltaic panels at 19 sites in South Africa and Namibia,” said Sanjeev Raghubir, sustainability manager for the Shoprite Group.

The search for alternative sources of energy is taking place as South Africa’s debt-laden state-owned utility Eskom continues to struggle.

Chief executive Andre de Ruyter issued a warning in March that at least another five years of power cuts were in the offing.

An ageing fleet of coal plants and severe engineering troubles at two mega-plants recently constructed to replace them have left the country with little reserve generating capacity.

Shoprite has fitted 650 solar panels to the roofs of its refrigerated lorries across the country. These allow drivers to switch off their lorries when they stop to make deliveries or collect goods from warehouses. This, says Mr Raghubir, reduces noise and exhaust pollution, while keeping the cold chain intact.

Shoprite is also on the point of securing a deal with a private electricity supplier.

“We are the first retailer to close such a deal, which is arguably the first of its kind in Africa.”

Cape Town, the second-largest city in the country, is also pursuing independent power suppliers, something that it is not technically allowed to do.

By law, Eskom has a protected monopoly, which the city is challenging in court.

While the issue is being settled, Cape Town’s city council is advising people to seek alternatives to Eskom.

“We are encouraging residents and businesses to invest in small-scale renewable energy technology,” said Phindile Maxiti, the councilman in Cape Town who leads the city’s energy committee.

City engineers have even prepared for net metering – making it possible for households to sell electricity back to the municipality.

“We are incentivising people by making it possible to feed electricity back into the grid and get paid for it.”

Other towns and cities are looking to do the same. In March, the Western Cape province said six of its towns were going partially off-grid, to run on wind, solar and other sources of power.

They would no longer depend on Eskom, which provides more than 90 per cent of the country’s electricity.

According to David Maynier, who holds the finance portfolio for the Western Province, every two-hour power cut cost the provincial economy 75 million South African rand ($5.1m).

“When it comes to the economy, Covid-19 is a left hook and load shedding is a right hook, which together often results in a knockout blow that risks compromising economic recovery,” he said during his March budget speech.

“This is a bold and ambitious project to support municipalities to generate, procure and sell their own power so that we can beat load shedding in the Western Cape.”

Even the cash-strapped government is moving ahead with alternative emergency power.

A couple of weeks ago, the government announced that it is bringing in "power ships" from Turkey.

These vessels are floating LNG power plants and will be docked at three different ports to provide electricity to the national grid.

“It is envisaged these projects will be connected to the grid from August 2022,” said Minister of Minerals and Energy Resources Gwede Mantashe. “This timetable is not negotiable.”

However, they will not be cheap as the deal will cost an estimated 218 billion rand over the life of the 20-year contract.

As the country goes to the polls for council elections for cities and towns later this year, power will be a key talking point.

The African National Congress, in control in parliament, has been sliding in local elections over the past decade and is eager to shore up support by strengthening the national grid.

In the meantime, businesses are preparing to fend for themselves. Gold Fields, one of the country’s largest mining groups, has begun work on a 50MW solar plant at its flagship South Deep gold mine.

US online retailer Amazon, which recently opened a 3,000-employee call-centre operation in South Africa, says it will also open a solar farm in the Northern Cape, a sun-drenched desert region.

“This is just the tip of the iceberg,” said Chris Haw, chief executive of the Solar Group, Amazon’s contractor and partner on the project.

“This is breaking open a pathway to much more procurement along these lines, and hopefully getting our country to a more resilient place while avoiding load-shedding in the future.”