India's renewable energy sector is set to power ahead, as investors look to capitalise on the sector's huge growth potential, helped by record low solar tariffs and rising demand that is set to double by 2040, industry insiders say.

This is in spite of challenges including project delays caused by the pandemic, as well ongoing issues such as as an ailing power distribution sector and difficulties securing access to land which, if addressed, could give the sector in Asia's third largest economy an even greater boost.

“India is one of the largest markets globally for renewables and is attractive to large investors,” says Vinod Kala, the founder of renewable energy consulting firm Emergent Ventures and a general partner at the Energy Impact Fund. “The investment environment is very positive, despite some challenges.”

The Indian government aims to almost double its renewable energy capacity by next year and increase it five-fold to 450 gigawatts by 2030. It has also pledged for the country to generate 40 per cent of its electricity from non-fossil fuel sources in the next decade under the Paris climate change agreement.

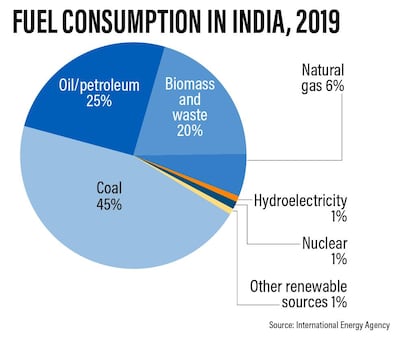

As well as being a way of reducing its carbon emissions, growing the use of renewables is seen as critical to meet India's expanding energy needs, improve energy security and reduce its dependence on costly oil and coal imports. The country is the world's third largest consumer of energy, with coal accounting for the bulk of this at 45 per cent. It is also the third-largest consumer of oil, with petroleum and other liquids making up 25 per cent of energy use, according to the International Energy Agency. India is the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases, the fourth largest oil refiner and a net exporter of refined products.

As India strives to boost the role of green energy sources such as solar and wind power, investors are eyeing further opportunities in the market.

“Domestic and global institutions across the financial, corporate, energy, utility and government sectors are primed to deploy a wall of capital that India needs to fund its ambitious renewable energy targets,” Tim Buckley, the South Asia director of energy finance studies at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA), said in a report published last week.

More than $42 billion of investment has been injected into India's renewable energy sector since 2014 and the country will require another $500bn to reach its 450GW target by 2030, according to the IEEFA.

“India is one of the world's largest and most promising renewable energy markets in the world, due to a combination of scale and abundant wind and especially solar resources,” says Andrew Hines, the co-founder and chief commercial officer at CleanMax, a renewable energy company based in Mumbai, which also has operations in the UAE.

The impact of the pandemic, however, has taken a toll on the development of India's non-fossil fuel industry, leading to some planned solar and wind power projects being stalled.

India's total addition of 4,908 megawatts of solar and wind power capacity in 2020 was the lowest in the last five years, according to a report by Bridge to India, a renewable energy consultancy. Utility-scale solar and wind capacity addition were 60 per cent and 40 per cent lower, respectively, on the previous year, its figures reveal.

This was caused by financial and operational challenges following the country's strict lockdown, including labour and equipment shortages as well as delays securing government approvals, the report said.

Despite the pandemic, there are signs investor confidence remains strong.

Last month, French oil giant Total invested $2.5bn into India's Adani Green Energy, for a 20 per cent stake in the company and a 50 per cent share in its portfolio of solar assets.

Patrick Pouyanné, the chairman and chief executive of Total, said “given the size of the market, India is the right place to put into action our energy transition strategy based on two pillars: renewables and natural gas”.

Mr Buckley says that IEEFA expects “global investors to accelerate deployment of capital as electricity demand continues to recover through 2021”.

The IEEFA report states that as well as fresh funds, refinancing is also required for green energy projects in India, and this capital is coming from private equity, sovereign wealth funds, oil and gas companies, and global pension and infrastructure funds.

Canada Pension Plan Investment Board and Malaysia's Petronas are among the global firms investing heavily in India's renewables industry.

Experts say investor demand will be spurred by low interest rates and lower solar tariffs that are making renewable energy more competitive.

“Wind and solar power are now some of the cheapest forms of power generation available, and that makes the case for renewables very compelling,” says Mr Hines.

Rahul Munjal, the chairman and managing director of Hero Future Energies, believes there are a wave of opportunities coming up in India following a subdued 2020. The renewable energy developer, based in New Delhi, received investment from Abu Dhabi's Masdar in November 2019.

“As India is just coming out of a year of [the] lowest solar capacity addition in the past five years, the sector has a lot of catching up to do,” says Mr Munjal. “I am expecting to see a spurt in large-scale utility bids by both state and central governments.”

But there are obstacles which need to be removed to allow the renewable energy sector to reach its full potential, he says.

“[India has] an ambitious [renewable energy] goal and for it to be achieved, certain policy, financial and technical constraints have to be addressed,” Mr Munjal says.

“The grid also must be upgraded to allow unhindered renewable energy penetration. This involves setting up transmission lines in new geographies and fast tracking of a green energy corridor.”

He adds that “as renewables growth requires massive amount of land, major land reforms will also have to be undertaken”.

Mr Munjal also wants to see an overhaul of the state-dominated power sector.

“We will have to rethink the viability of electricity companies and privatisation is the way forward,” he says.

Mr Hines believes that the renewable sector could benefit from longer-term strategic planning from the top to facilitate further investment and development.

“As power generation, transmission and distribution are heavily regulated industries ... the industry is dependent on policymakers and regulators to create an environment which is conducive to an increasing share of renewable energy in the grid,” he says. “A focus on transmission and grid balancing is important as the share of renewables increases.”

Some solar and wind developers have reported challenges with delayed payments from power distribution companies, and the state of Andhra Pradesh in 2019 suddenly decided to renegotiate renewable purchase power contracts, which irked developers and investors.

“A rapid decline in renewable prices has resulted in a dilemma before some utilities as the old tariffs appear high compared to tariffs discovered in recent bidding,” says Mr Kala.

For many investors, though, the potential gains outweigh the risks.

“We been focusing on supporting green small and medium size businesses and start-ups providing innovative new climate solutions or those who play [a] pivotal role in deployment and expansion of the industry,” says Viswanatha Prasad, the managing director and founder of Indian investment firm Caspian Debt.

“We're an impact investor with a mandate of investing for generating financing returns while supporting entrepreneurs building a better world [and] climate and sustainability is one of the central investment themes of the fund.”

But Ashvin Patil, the director of Biofuels Junction, explains that the biggest boost for the renewable energy industry in India would come from a greater push by corporates and authorities to move away from the use of polluting energy sources.

By raising the level of its energy efficiency, India could save some $190bn a year in energy imports by 2040 and avoid electricity generation of 875 terawatt hours per year, almost half of India’s current annual power generation, according to the International Energy Agency.

“We believe the renewable sector can get a boost if the government implements pollution parameters limits strictly,” Mr Patil says.