The temporary closure of Libya’s largest oilfield this month following protests underlines the lingering shadow of political instability on the North African country’s embattled oil and gas industry.

The Sharara oilfield, with a capacity of 300,000 barrels per day, was shut down on January 7 following protests by residents demanding better infrastructure and economic opportunities.

Libya's state-owned National Oil Corporation (NOC) announced the resumption of operations at the facility on Sunday.

The field represents roughly a fourth of the country’s total output of about 1.2 million barrels per day.

Such protests, which target the country's vital oil infrastructure, may affect the Opec member’s ability to meet its lofty production target and grow its gross domestic product over the next few years, according to analysts.

Despite having Africa’s largest crude reserves, a third of Libya’s population lives below the poverty line and parts of the country suffer chronic shortages of petrol and gas due to inadequate investment in pipelines and refining capabilities.

“Considering that the Sharara oilfield is the largest one in Libya, recovering or falling production from that field has a big impact on revenues of the NOC,” Giovanni Staunovo, a strategist at Swiss bank UBS told The National.

“International oil companies (IOCs) are likely [to have] a cautious approach in respect to returning to the country considering the political instability and risk of production disruptions,” he said.

Last week, the country's oil minister said that the continued shutdown of the key oilfield could potentially impact the nation's GDP and undermine Libya's reputation as a reliable energy supplier.

“We believed the country had achieved stability, and customers had confidence in receiving consistent oil quantities. Losing customers is a real risk, jeopardising the future for everyone,” Mohamed Oun told reporters at an event in Tripoli.

“It's crucial for people in Libya to understand that the NOC and the Ministry of Oil and Gas are primarily focused on oil and gas exploration, extraction, production, and contributing revenue to the country's state treasury,” he said.

The last time Libya suffered a major supply disruption was in 2022.

Military commander Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, whose forces control the oil-rich eastern Libya, orchestrated a blockade on fields and ports that year, prompting NOC to declare force majeure for exports.

The blockade was lifted following the appointment of Farhat Bengdara as NOC chairman.

Political tangle

Libya has remained divided since the civil war that ensued following the 2011 revolution.

The western part of the country is governed by the internationally recognised administration known as the Government of National Unity (GNU), which was established through a UN-led political process ahead of elections scheduled for December 2021.

However, these elections did not take place, leading to challenges from opponents questioning the legitimacy of the GNU's authority.

In the eastern region, a rival government called the Government of National Stability emerged in March 2022, taking control of about three-quarters of the country's oil production capacity.

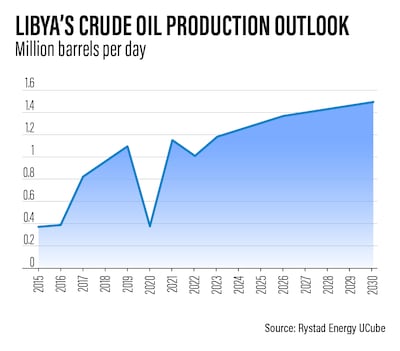

NOC, which restored its output to 1.2 million bpd last year, said in October that it planned to increase its crude production to 2 million bpd over the next three to five years.

The state-run energy company, seeking to reactivate old oil wells and launch fresh exploration activity, aims to bring in IOCs.

Mr Bengdara has indicated that the planned output increase would necessitate $17 billion in investments across 45 projects.

“[It is] a huge commitment for IOCs when it comes to Libya, considering the unstable atmosphere,” Rystad Energy said.

“Additionally, Libya currently still has two parallel governments with no centralised decision-making body, making announcements such as elections potential triggers that could once again lead to production losses,” the Norway-based consultancy said.

Rystad Energy expects Libya to reach a production level of 1.4 million bpd by 2027 in its base case scenario and 1.8 million bpd in its high case scenario.

Wood Mackenzie said the target of 2 million bpd would not be reached even in the US-based consultancy’s most bullish case.

“The spectre of oil production shut-ins continues to hang over Libya. And alongside outages from ageing infrastructure, investment will remain too low to achieve significant increases in the short to medium term,” Wood Mackenzie said in November.

“If Libya can improve security and fiscal terms, then there is significant longer-term upside,” it said.

Before the protests this month, there had been renewed interest from energy companies in the country’s oil and gas industry.

Last year, Eni, BP and Algerian energy company Sonatrach announced the resumption of their operations in the country after a 10-year absence.

In January 2023, Eni and NOC signed an $8 billion gas production deal, which could result in a production of up to 760 million cubic feet of gas.

Libya is set to conduct a licensing round in the fourth quarter of this year, its first in almost two decades.

Banking on oil

Crude oil and natural gas export revenue account for a significant part of Libya’s economy.

In 2021, oil revenue accounted for 56.4 per cent of the country’s GDP, compared with 42.8 per cent for Iraq and 23.7 per cent for Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest oil exporter, the World Bank said.

For Nigeria, Africa’s largest crude exporter, oil revenue only made up 6.2 per cent of its GDP in 2021.

Libya's real GDP is projected to rise by 7.5 per cent this year, after growing an estimated 12.5 per cent in 2023, the International Monetary Fund said. Its economy contracted by 9.6 per cent in 2022.

Following the devastating floods that hit the country in September last year, the IMF said Libya’s medium-term economic outlook remained positive due to high oil prices.

The floods in Libya inundated about a quarter of the city of Derna after torrential rain from Storm Daniel caused two dams to collapse near the eastern port city.

However, it did not disrupt the country’s crude output.

Libya plans to increase its GDP to about $250 billion and have oil and gas as 40 per cent of the economy, Economy Minister Mohamed Al Hwej said during the Tripoli event last week. He did not provide a timeline or any further details.