As schools and universities in India were forced to close due to the coronavirus pandemic and with students turning to digital learning, Kopykitab,a digital learning platform, found its servers were being overwhelmed.

At times, there was so much unexpected demand for his company's online education services over the past year that its system could not cope, the company's co-founder Sumeet Verma says.

“We had multiple instances of our cloud server getting choked with traffic,” Mr Verma, who is also the chief executive of the Bangalore-based company that offers online classes and e-books, says. “That was a good problem to solve.”

Backed by investors including the Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, Kopykitab has seen its monthly active users grow from 800,000 per month before the pandemic to 2.8 million today.

“It takes a lot of time to change consumer behaviour but the pandemic amplified everything,” says Mr Verma. Prior to that, India's education technology market was “evolving”, he says. Companies like his saw themselves as “working for the future”.

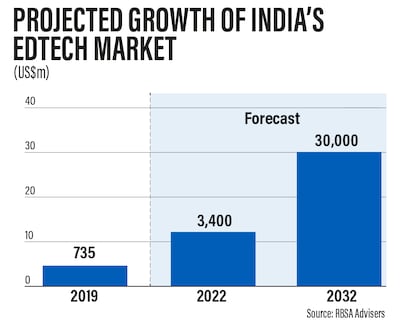

India's EdTech sector is expected to grow in value to $30 billion in the next decade from about $735 million to $800m in 2019, according to a report published in April by RBSA Advisers.

Along with the boost from the pandemic, “the introduction of EdTech has coincided with growing internet penetration with availability of cheaper smartphones and low data prices”, says Rajeev Shah, managing director and chief executive of RBSA Advisers.

This is increasing access to online education in a country which has one of the largest education systems in the world, with a population of 430 million between the ages of six and 23. In the past year, more start-ups have entered the market to offer much-needed digital lessons during the pandemic.

Despite this, the EdTech sector in India is still nascent compared to the likes of the United States and China, meaning there is still enormous scope for growth. Investors have been keen to get on board.

“Indian EdTech has been on investors' radars for quite some time now,” says Devendra Agrawal, founder and chief executive of Dexter Capital Advisers.

“2020 was a very good year to raise capital for EdTech”, he adds, explaining that the sector saw more than 50 start-ups raise $1.9bn, which was three times the amount secured in the previous year.

“The investor interest stems from India’s obsession with top grades, admission to top colleges and landing lucrative jobs,” says Mr Agrawal.

This has driven the growth of Byju's, which is by far the largest player in the space and considered a pioneer in the sector. The tutoring app for schoolchildren was founded in Bangalore by 2011 by Byju Raveendran, who himself worked as a tutor and whose parents were teachers. Bloomberg reported last month that fresh funds being raised from UBS Group would make it India's most valuable start-up, with a valuation of about $16.5bn.

Byju's recently raised $1bn from investors including Facebook co-founder Eduardo Saverin's B Capital Group, according to Bloomberg, as the company continues to expand and has been making acquisitions in the sector.

RBSA's research shows that India has become one of the top three countries after China and the US for venture capital funding in EdTech.

Raising funds for some start-ups could be more challenging this year, though.

“In 2021, we are seeing some overheating in the market and the emergence of ‘me-too’ businesses seeking capital,” Mr Agrawal says, explaining that start-ups will have to work harder to demonstrate differentiation and growth.

However, he adds that “the outlook is certainly bright for the overall space as India is a sizeable market and parents are always ready to loosen their wallets for their kids’ education and learning”.

Achin Bhattacharyya, the chief executive and founder of EdTech company Notebook, explains that the fact that Indians place such importance on education will propel the sector over the coming years.

“India is one country where you see that a parallel system of education not only exists, but thrives,” he says, explaining that coaching centres are prevalent across the country, from cities to villages, which many children would normally attend alongside their regular schools.

“The pandemic has fast-forwarded the entire process of online education,” says Mr Bhattacharyya.

“In many cases teachers, parents, many of them were hesitant about digital education, but the pandemic has ensured that they are left with little choice.”

Sunita Gandhi, an educator and founder of the Global Education & Training Institute, India, which offers online training to teachers, explains that there is still a lot of work to do when it comes to developing digital education.

“During and due to the pandemic, there has been a surge in developing EdTech tools to enhance and provide education online with the use of technology,” says Ms Gandhi. “However, the way to push these tools in the market is not very clear. People are still struggling to use social media and technology for education in the real world of school and home schools.”

It is not only schoolchildren and university students who are turning to online education. Another trend in the sector that has been driven by the pandemic is demand for online courses from those who have lost jobs or are looking to boost their skills as they spend more time working from home.

“In India, the EdTech sector had been primarily restricted to the test prep and K-12 segments, but people had not concentrated on passion-based learning or upskilling,” says Ruhan Naqash, co-founder of MyCaptain, which offers live online classes in fields ranging from finance to photography. “But during the pandemic, people have been taking up online courses that they were really interested in.”

Shantanu Rooj, founder and chief executive of TeamLease Edtech, which works with corporates and higher education institutions, says there has been “an emergence of a new class of learners, because there have been job losses and a realisation among corporate employees that people should upskill themselves”.

There is also the question of whether online learning will continue to play such a big role after the pandemic. India is currently undergoing a massive second wave of Covid-19. More than 257,000 new cases were reported on Saturday, bringing the total to more than 26.28 million, according to government figures. Although many schools had reverted, or were planning to revert, to classroom-based learning earlier this year, parents and teachers are now realising that there is likely to be a longer term need for online learning, Mr Rooj says.

He points out, however, that while internet access is improving in India, there are still large numbers of citizens in poverty and in rural parts of the country that do not have access either to the devices or the good internet connectivity needed for online learning.

Still the EdTech market is forecast to continue growth as the government pushes its “Digital India” initiative.

“It will grow driven by new reforms, including the increase in public spending targeted at 6 per cent of the nation’s gross domestic product [on education], relaxation in regulations governing degrees and need realisation among students and professionals” according to a report by RedSeer Consulting.

Mr Verma at Kopykitab says that India “is just scratching the surface” when it comes to EdTech.

He says the company is currently looking to raise funds as it considers overseas expansion – a process that may be delayed because of the pandemic's second wave, which is preventing in-person meetings with investors, he says.

He remains upbeat on the sector's long term prospects, though.

“India would be an EdTech exporter eventually.”