The arrival of spring in the southern hemisphere will bring little joy to many South Africans, who are now officially poorer than when winter began.

On Tuesday last week the country entered a technical recession as gross domestic product decreased by 0.7 per cent in the second quarter of the year. This follows a GDP contraction of 2.2 per cent in the first quarter. A technical recession is two consecutive quarters of contraction.

For many South Africans this just confirms what they’ve been experiencing for some time now. “Food just keeps getting more expensive,” says Jake du Plooy, a science student at Nelson Mandela University in Port Elizabeth. Mr du Plooy’s parents give him 1,200 (Dh288) rand a month food allowance. “It’s mincemeat and beans mostly. By the end of the year it will probably be just the beans,” he says.

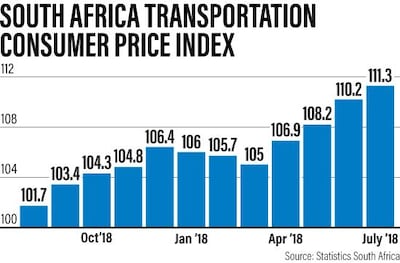

The country's annual inflation rate has surged from 3.8 per cent in March to 5.1 per cent in July, hitting residents in the pocket when it comes to paying for food, other essentials and transport.

At least Mr du Plooy, from a white middle-class family, gets an allowance. Some of his fellow students – mostly from poor black households, are dependent on unreliable government grants. Lecturers have started bringing in food packages they buy themselves to give to those in most need, Mr du Plooy says. Some people have been forced to turn to loans firms that often charge ruinous interest rates.

The South African currency, the rand, has lost 15 per cent against the US dollar this year, adding pressure to the price of imports. The currency was at 15.15 to the dollar around 1pm UAE time on Monday, a slight recovery from 15.42 on September 5, which itself was the weakest since January 18, 2016, when it hit 16.88.

The cost of fuel is especially vulnerable to a weak rand. The majority of commuters depend on public transport, using a network of mini-buses known locally as taxis to get to and from work. Fuel prices are currently at a record breaking all time high in South Africa. According to the UK-based AA's (Automobile Association) office in South Africa office, the price of a litre of unleaded 93 petrol is today 15.86 rand, the equivalent of Dh3.83. By comparison, the price of Special 95 per litre in Abu Dhabi is Dh2.48.

In a rare move, the government, which sets the fuel price monthly depending on the imported cost, held back on a big price adjustment in September, raising the cost of petrol by just 5 cents, even though the imported cost per litre rose nearly 30 cents.

"Taxi drivers tell us petrol goes up so the price of taxis go up," says Limukani Hadebe, preparing to board a minibus in central Cape Town. "It doesn't matter if the government is holding back the price increase this month. They'll make us pay the extra next month."

Meanwhile, any consumer relief such as a fuel subsidy is likely to put more pressure on the already cash-strapped Treasury. “And in yet more good news government has agreed to absorb 25 cents of a 30-cent increase in the fuel price,” says human rights attorney Richard Spoor. “The only problem is that no one knows where government will find the money to pay for this.”

_______________

Read more:

South Africa's central bank chief puts independence centre stage

South Africa slumps into recession for first time since 2009

_______________

The country heads to elections within the next year, and it is likely the ruling African National Congress will continue to use tactics such as the fuel subsidy to bolster the party’s sagging popularity. However, increased public spending could cost South Africa its last investment grade rating, held by Moody’s. Moody's has kept South Africa's local currency debt rating at one notch above "junk" status, whilst Fitch Ratings and S&P have the country already at junk status.

“It may be pre-election giveaway season, but spending decisions need to be carefully thought through,” says Razia Kahn, chief economist for Africa at Standard Chartered Bank in London. “There’s no point in sacrificing the last investment grade rating for short-term, questionable gain.”

The decline in GDP was led by agriculture production, which fell by 29.2 per cent in the second quarter of 2018, following a 33.6 per cent plunge in the first quarter. The country is currently locked in a debate around the seizing of white-owned land without compensation. However, economists say a record-breaking drought in the Western Cape that saw the city of Cape Town itself nearly run out of water was the cause of a fall in farming’s economic contribution, not political uncertainty.

“The uncertainty regarding land reform policy, particularly expropriation without compensation, remains a key risk that could potentially undermine investment in the agricultural sector,” says Wandile Sihlobo, an agricultural economist and head of agribusiness research at the Agricultural Business Chamber of South Africa. “At this point, however, farmers are somewhat in a wait-and-see mode. We have not seen a notable dent on investments in the sector yet.”

Not only South Africans will feel the pain of a recession. As Africa’s largest industrial economy, the effects will not be confined to its borders. The Institute of Social and Economic Studies (Ises) in Mozambique warns that the recession will also hurt that east-coast nation.

South Africa accounts for a third of Mozambique’s imports, Ises says. "This will generate inflationary trends [in Mozambique], especially for basic necessities.”

More worrying is how it will play out for the half a million or so Mozambicans working in South Africa, sending home remittances. Some could lose jobs, cutting the flow of income across the border. Those who remain may be vulnerable to violence by locals, who accuse them of taking jobs.

Ises says that "unemployment in South Africa may have negative effect on the remittances of Mozambican workers. And there is a risk of another wave of xenophobia."

While a sinking tide lowers all boats, some at least will ride out the recessionary storm. Cape Town watch specialist Philip Zetler buys and sells collectable timepieces such as Patek Philippe, Rolex, Cartier and other luxury brands.

Mr Zetler hopes his rich clients will continue to spend money on such costly vanity items. Men with wealth will seek accessories that are a visible display of that wealth which they can display on their person, he says.

"It's one of the few pieces a man can buy for himself, as a reward for being a success," Mr Zetler says.

"Women have far more options but a man's wrist becomes the place to strap on a piece of art that the world can see."

When it comes to luxury vehicles, the current recession is unlikely to hurt those who can afford them. The new Rolls-Royce Phantom, for instance, was unveiled in London at the end of last year and the first arrived in South Africa in January. Johannesburg-based Rolls-Royce Motor Cars Sandton did not reveal the price but in any case that was academic - the entire 2018 allocation of South Africa-bound Phantoms was already sold out.