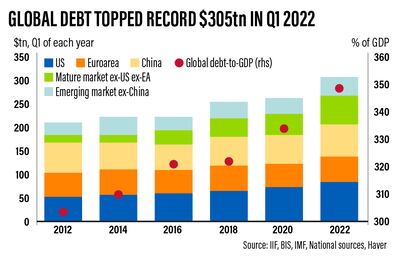

Global debt surged to a record $305 trillion in the first three months of this year as the US and China, the world’s two largest economies, continued to borrow amid slowing economic growth exacerbated by Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Total debt climbed by $3.3tn in the January-March quarter, the Institute of International Finance said on Wednesday.

At more than 348 per cent of global gross domestic product, debt is about 15 percentage points below its peak in the first quarter of 2021, according to the IIF.

Reflecting the surge in inflation, the global debt-to-GDP ratio declined for the fourth consecutive quarter in the first three months of this year. The drop was more evident in mature markets.

“As the ripple effects of the Russia-Ukraine war continue to disrupt global economic activity, [economic] growth is expected to slow significantly this year, with adverse implications for debt dynamics,” IIF said in its Global Debt Monitor report.

“On the back of strict lockdowns in China and tighter global funding conditions, the anticipated slowdown will likely limit or even reverse the downward trend in debt ratios.”

Although global debt was largely driven by $2.5tn and $1.8tn borrowings by China and the US, respectively, in the euro area it declined for the third consecutive quarter.

The surge was underpinned by corporate sector borrowings — excluding financial institutions ― and general government borrowing, with debt outside the financial sector now topping $236tn — nearly $40tn higher since the onset of the pandemic. Cumulative debt in emerging markets is now approaching a record $100tn, the IIF said.

The inflation outlook will also play a role in global debt and will continue to help reduce debt ratios in general.

“As central banks move ahead with policy tightening to curb inflationary pressures, higher borrowing costs will exacerbate debt vulnerabilities,” the IIF said. “The impact could be more severe for those emerging market borrowers that have a less diversified investor base.”

Governments and central banks around the globe have poured an estimated $25tn in fiscal and monetary support to stabilise financial markets and minimise the effects of the pandemic on their economies. They borrowed extensively during the past two years to shore up finances and bridge fiscal gaps during a period of historically low interest rates.

However, the US Federal Reserve has started raising interest rates to combat inflation that hit 40-year high. The Fed plans to continue increasing benchmark rates this year and next, which will raise borrowing costs, particularly in emerging markets.

The war in Ukraine and sanctions on Russia have worsened global growth and inflation prospects. The International Monetary Fund lowered its 2022 and 2023 growth forecasts for the global economy to 3.6 per cent, revising it down 0.8 and 0.2 percentage points respectively from an earlier estimate.

Many emerging and mature market economies have entered the Fed’s latest rate hike cycle with high levels of dollar-denominated debt, the IIF said.

Since the onset of the pandemic, global government debt has risen by 14 percentage points, or $17.4tn, to 103 per cent of global GDP by the end of the first quarter of this year.

Faced with rising borrowing costs, sovereign balance sheets are under pressure. Financing needs of governments are still well above pre-pandemic levels, while higher and more volatile commodity prices could force some countries to increase public spending even further to ward off social unrest — especially if their economic growth remains lower than expected.

“Interest expense is becoming an increasingly heavy burden for sovereigns”, with sharp projected increases across mature markets, the IIF said.

The higher interest rate situation is particularly difficult for emerging markets that have less fiscal headroom, it said.

Non-financial companies have piled up more than $14tn of new debt since 2019, bringing total non-financial corporate debt to over$90tn at the end of the first quarter of this year.

While very large cash holdings of publicly listed companies provide a buffer against adverse shocks, rising debt levels have increased the sensitivity of corporate balance sheets to soaring interest rates.

Rising financing costs, coupled with heightened geopolitical risks, erased more than $16tn from global stock markets this year.

“One third of small-sized firms in mature markets are now facing difficulty covering interest expenses, making it particularly challenging for central banks to engineer a soft landing this time around,” the IIF said.

The sharp reversal in global risk appetite and economic uncertainty stemming from Russia’s military offensive in Ukraine has also forced a marked slowdown in debt for projects and deals adhering to environmental, social and governance standards.

“However, the growing focus on energy independence should accelerate efforts to scale up climate finance, supporting the development of climate and, more broadly, ESG debt markets going forward,” the IIF said.