India has the ambition and the capacity to fill at least part of the global wheat supplies gap, an agricultural chemicals company chief has claimed. Russia's military offensive in Ukraine severely hampers wheat exports from both countries, which collectively account for more than a quarter of global supplies of the commodity.

However, the current supply gap presents an enormous opportunity to India to explore its agricultural potential and boost wheat exports, said Vimal Alawadhi, managing director at Indian agricultural chemicals company Best Agrolife.

“Now, when the world is banking on us to fill the supply gaps arising from the Russia-Ukraine conflict, we have a great opportunity to emerge as a global wheat superpower,” said Mr Alawadhi.

However, fears remain that the quality of shipments and logistics could hold back the third-largest Asian economy from achieving its full market potential.

About half of India's population depend on agriculture for their livelihood and the sector accounts for about 20 per cent of the country's gross domestic product, according to government data. But the sector has struggled with profitability in recent years, making it even more critical for India to capitalise on this opportunity.

Before the war in Ukraine, Russia was the world's largest wheat exporter and Ukraine the fifth, according to the World Bank data. Russia accounted for 17.6 per cent of the global share of wheat export revenue, or $7.9 billion worth, in 2020, while Ukraine held an 8 per cent share of the market, according to data from research portal World's Top Exports.

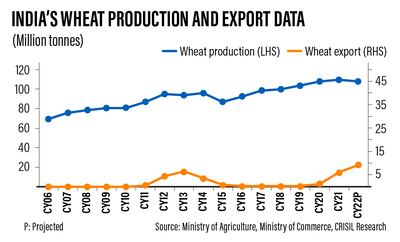

However, India accounted for just 0.5 per cent of wheat exports in 2020, despite it being the world's second-biggest grower of the commodity. It produces more than 100 million tonnes of wheat per year, placing it second only to China.

Sanctions imposed by the US and its allies in Europe against Moscow and the devastation in Ukraine — often referred to as the bread bowl of Europe — mean that importers who have depended on Russia and Ukraine for their wheat supplies are now having to find alternatives. The supply crunch has pushed global wheat prices to record highs in recent weeks.

With little or no prospects of de-escalation in the short- to medium-term, supply scenario is not going to improve anytime soon, putting wheat-importing nations in a tight spot.

“Today there is a huge demand for Indian wheat in the international market,” said Mr Alawadhi.

“We must focus on becoming a long-term exporter to these countries and to ensure this we need to export only good quality wheat to them.”

While there has been a surge in global prices, India's wheat rates are relatively competitive, analysts say, which is another factor working in its favour.

But one of the main hurdles that could hold back India's exports is the quality of its grain. Impurities in some of India's produce means that some buyers are wary of sourcing wheat from the country. The quality determines whether the grain can be used for making food products including bread and pasta.

“Despite having surplus wheat stocks for some years, quality concerns have in the past stymied India's efforts to sell large volumes on the world market,” according to a new report by S&P Global Commodity Insights.

India wants to grasp this unique chance to boost exports and traders have already started shipping more of the commodity abroad.

“If the World Trade Organisation (WTO) gives permission, India is ready to supply food stocks to the world from tomorrow,” Narendra Modi, India's prime minister said earlier this month, as he spoke about the challenges arising globally due to supply shocks caused by the war in Ukraine.

Feeding more than 1.3 billion of India's own population should not be a problem as the country has enough stocks, Mr Modi said.

The issue of export restrictions was also raised when Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman visited the US last week.

India has already identified opportunities to boost its wheat exports and it is working on them, However, it is facing difficulties in exporting grains because of WTO restrictions, the Press Trust of India cited Ms Sitharaman as saying at a plenary session, which was also attended by the WTO's Director-General, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala.

Ms Sitharaman said the Indian government has received a positive response from the WTO to address this matter.

“I hope we'll break that decade-long restriction which has held us back from using our agricultural products after taking care of the buffer we need for food security purposes, so that the farmers also can get a better return,” Ms Sitharaman said.

In recent years, India has mainly exported wheat to countries including Bangladesh, which receives about half of India's shipments of the grain, the UAE and Sri Lanka.

But new, promising export avenues are opening up and several countries including Turkey and Lebanon are potential new major growth markets for India, analysts say.

Egypt, which is the biggest importer of wheat from Russia and Ukraine, has already approved India as a supplier, India's commerce and industry ministry announced this month.

S&P Global, however, says that India may fall short of its target of shipping 3 million tonnes of wheat to Egypt in the current fiscal year, and may only achieve exports of 1 million tonnes, due to “quality and logistics issues”.

This represents less than a 10th of Egypt's total annual imports of the grain.

However, Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal said India is “stepping in" as the world looks for reliable alternate sources for steady food supply.

"Our farmers have ensured our granaries overflow and we are ready to serve the world,” he said a tweet announcing the Egyptian deal.

India can increase its wheat exports during this financial year to at least 10 million tonnes, which would be a record high, and possibly reach 15 million tonnes, according to Mr Goyal. In the previous year, official figures show that the most India has managed to export is 7 million tonnes of wheat in the past.

The government has outlined plans to send trade delegations to countries including Morocco, Tunisia, the Philippines, Vietnam, Turkey and Lebanon.

“With wheat exports from Ukraine and Russia hit due to the conflict and sanctions, we see bright prospects for Indian produce in export markets,” according to a report by Crisil Research, an Indian ratings and research company.

While there have been some concerns about the impact that ramping up exports could have on India's domestic demand for wheat, the country is anticipating a surplus this year. Crisil says that including wheat stocks carried over from last year, the country's wheat supply for the year will reach 147 million tonnes, while domestic consumption is forecast at 105 million tonnes.

“India, if it manages to cash in on the opportunity, will be able to export 45 to 50 per cent more wheat this calendar [year], that too, over a significantly high base of 2021,” according to Crisil report.

There is a potential downside, however.

As exports reduce India's stocks, this could push up the price of the grain by 8 to 10 per cent on the year in the first quarter of this financial year, Crisil projects.

This would make wheat more expensive for households already struggling with rising food prices, which have propelled India's retail inflation to a 17-month high of close to 7 per cent last month, according to official data.

“As wheat is an Indian staple, the government may be forced to curb exports, as it has done earlier,” Crisil warns.

“In 2007, when wheat prices had surged 11 to 12 per cent following a global price rally, the government banned its exports to tame inflation. The ban stayed until 2011.”

Suseelendra Desai, dean of the School of Agriculture Sciences and Technology, at NMIMS University in Shirpur, says there are other possible hurdles to consider. Thee include extreme weather events that could affect crops and the productivity of export-suitable varieties of wheat in the country.

“The new opportunities could be those markets hitherto served by Ukraine such as Europe,” said Mr Desai.

But he said that catering to Europe would be “subject to fulfilling the rigorous EFSA [European Food Safety Authority] quality standards”, which poses a challenge.

S&P Global says that the quality of India's wheat is negatively affected by deficiencies of micronutrients, including zinc, copper and iron.

There has also been a fall in the crop yield and shrunken grain size in the states of Punjab, Haryana, and Uttar Pradesh “due to excessive heat and improper use of fertilisers and pesticides”, This has “dimmed our chances”, Mr Alawadhi said.

The Ukraine crisis means that there is “an opportunity for India” to export large amounts of wheat, Taranjeet Bhamra, founder and chief executive at AgNext Technologies, said.

Insufficient port infrastructure to cater to surging demand, as well as higher freight costs, could prove to be obstacles, he added.

However, the country is well-positioned to meet all challenges head-on and fulfil "all quality expectations”, Mr Bhamra said.