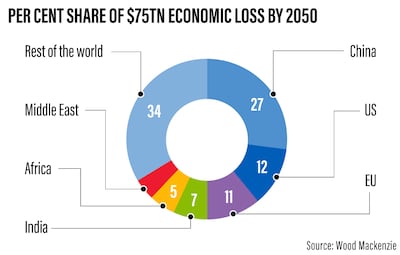

An accelerated energy transition to mitigate climate risk will have tangible economic implications and may shave $75 trillion off global gross domestic product between 2022 and 2050 as countries push to meet their climate commitments.

The global economy is set to double in size in real terms, rising to $169tn by mid-century from the current $85.6tn, Wood Mackenzie said in its latest report detailing economic consequences of energy transition.

Under its base case scenario, the research company expects temperatures to reach 2.5-2.7°C above pre-industrial levels by mid-century. However, to limit this warming to 1.5°C, in line with the Paris climate pledge, the energy transition will have to accelerate.

Measures to lower temperature will boost global GDP, on aggregate, by 1.6 per cent by 2050, Wood Mackenzie estimates. At the same time, however, the actions required to successfully mitigate climate risks could slash output by 3.6 per cent. The push to cap levels at 1.5°C agreed in the Paris Climate Accord will result in net drop of about 2 per cent by 2050.

“While preventing more extreme warming is likely to have a positive economic impact over the next 30 years, the action required to deliver it could have an offsetting negative effect,” Peter Martin, Wood Mackenzie’s chief economist, said.

“The cumulative loss of $75tn over 2022 to 2050, while material, amounts to just 2.1 per cent of total economic output over the period.”

Some economies will feel the effects of accelerated transition more than others. Economies that are already closer to net-zero targets will see a smaller impact from now to 2050, according to Wood Mackenzie research.

“For a fortunate few, the transition need not result in economic loss at all,” Mr Martin said.

“Those that are better positioned – typically wealthier economies with a strong propensity to invest in new technologies – may even benefit by 2050.”

However, “what is not in doubt is that the economic impact of energy transition will not be felt evenly”, with less developed and low-income economies likely to bear a “disproportionally high burden” during the transition.

Some of the hydrocarbon exporting and carbon-intensive economies are likely to see the biggest hits to economic output. Climate finance for lower-income countries, including government transfers and private sector investment, can help address inequity.

Pledges by governments around the world to mitigate climate risk have come into sharp focus during Cop26 in Glasgow last year, with global leaders pushing to accelerate the energy transition.

Rich nations also secured the long-awaited $100 billion a year funding for developing countries to help them meet their climate targets. The funding is set to be delivered in 2022, a year earlier than previously thought. However, Wood Mackenzie said more needs to be done.

“A truly fair and just transition will require actions to exceed our current expectations,” it said.

To determine the distribution of the GDP impact, researcher have assessed countries on their resilience to climate change and the impact of actions to avoid it.

Economies with high renewable energy capacity in power generation and advanced power grids are well placed for a low-carbon future. Those that are better positioned are, typically, wealthier economies with deep capital markets and a high propensity to invest in new technologies or an existing presence in nascent transition sectors, the research showed.

chief economist, Wood Mackenzie

Some of the hydrocarbon-exporting economies with large fiscal buffers are also well-placed. However, others, such as Iraq, are not.

“Iraq is the country most vulnerable to the energy transition, with hydrocarbon revenues accounting for 95 per cent of all government revenue and the oil sector making up 36 per cent of GDP,” Mr Martin said.

“An accelerated energy transition would slash Iraq’s GDP by 10 per cent in 2050 versus our base-case outlook.”

The world has the means, motive and opportunity to cap global warming. It is imperative to avoid environmental and humanitarian crises wrought by extreme temperature increases, the report said.

“An accelerated transition could pay off in the end, in economic terms,” Mr Martin said.

“It is likely to lead to stronger economic growth rates for some economies beyond 2030, enabling losses to be recouped before the end of the century.”