The never-ending controversy over climate change has at least achieved one thing: it's debunked the notion that the more we find out about something, the more certain our understanding becomes.

From the link between air pollution and global temperatures to the role of clouds in keeping the Earth warm (or maybe cool), the science of climate change just gets ever more confusing.

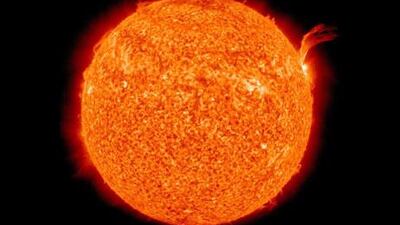

Now there's evidence that the role of the key driver of the Earth's climate may have been fundamentally misunderstood. The Sun, it seems, may not warm our world according to the laws of common sense. This will come as an unpleasant surprise to those climate scientists who habitually respond to scepticism about their predictions with the mantra "the science is settled".

Not everyone has been so sure about that, however - and not all are nay-sayers in the pay of oil companies. They include many leading scientists, among them over 40 Fellows of Britain's Royal Society, the world's most venerable scientific academy. They have criticised the peremptory tone adopted by some in the climate debate, and took particular exception to a guide to the science of climate change issued by their own institution in 2007. They believed more emphasis should be put on the uncertainties surrounding the science.

Now they appear to have got their way, with the publication last month of a revised guide by the Royal Society. While the new version still rightly insists there is strong evidence that global warming is largely due to human activity, it also points out the uncertainties surrounding other potential drivers of climate change. Among these is the most obvious driver of all: the Sun.

The report says that while the Sun's output can and does vary over time, these aren't thought to have played a major role in climate change over the last 150 years. It does, however, concede that direct measurements of the Sun's output have only been available since the 1970s, and the potential mechanisms that could boost or reduce the Sun's impact on the climate "remain areas of active research".

As luck would have it, last week the Royal Society's more nuanced guide ended up appearing almost spookily prescient. Scientists carrying out this "active research" made headlines with evidence suggesting the Sun's role in climate change may need a major rethink.

Astronomers have known for over 150 years that the Sun undergoes a cycle of activity roughly 11 years long, during which the number of sunspots rises and falls. Since the 1970s, satellite data have also shown that the Sun's heat output also goes up and down in synchrony with the sunspots. The variation is pretty small - around 0.1 per cent - but one of the key features of the climate is its so-called non-linear response; in other words, its potential sensitivity even to small changes. So climate modellers have included the boost the Earth's temperature receives when the Sun is active, and the reduced effect when the Sun calms down again.

All of which seems perfectly sensible - except it may be precisely the opposite of reality. After studying satellite data about the sunlight falling on the Earth, a team led by Dr Joanna Haigh at Imperial College, London, has found that the Sun may have its biggest impact on the climate when it is least active.

The team made its surprising discovery after trawling through daily measurements of the sunlight reaching the Earth between 2004 and 2007, made by Nasa's Solar Radiation and Climate Experiment (SORCE) satellite. The satellite does not merely measure the intensity of the sunlight, but also its wavelength - a crucial factor that holds the key to the discovery. That's because when it comes to climate effects, it is vital to differentiate between the different types of sunlight. At ground level, the Sun's heating effect comes mainly in the form of visible and near-infrared sunlight, but at higher altitudes it's the shorter, ultraviolet wavelengths that have the biggest effect.

The SORCE measurements covered a period at the end of the last solar cycle, when both these forms of heating should also have been declining. Sure enough, the team found that levels of ultraviolet did decline - but by far more than they were expecting, dropping to barely 20 per cent the predicted value. More surprising and significant still, the amount of heat reaching ground level actually increased, producing an overall warming.

These perplexing results, which appear in the current issue of the journal Nature, have prompted responses ranging from excitement to incredulity. One space physicist told Nature that taken at face value, the data "seem incredibly important". Their real significance and reliability remains far from clear; the researchers themselves stress that their findings do not even cover a full solar cycle, and could prove to be a short-term quirk.

But for climate change sceptics, the real significance of the findings lies in the warning shot fired across the bows of those who believe the science of climate change is settled. If we don't even understand the source of the world's warmth, they argue, how can we presume to predict the future temperature of our planet? Furthermore, does it make sense to take immediate action to combat global warming, when it will take at least several solar cycles - several decades, in other words - to confirm or refute these latest findings?

If nature does prove to be using the Sun to play tricks on us, it won't be the first time - as Professor Frank Close explains in his book Neutrino, published this week. Back in the 1970s, measurements of the Sun's output showed it wasn't pumping out anything like the expected numbers of sub-atomic particles generated deep within the Sun's core. So big was the discrepancy that some scientists - including Prof Close - felt moved to ponder the terrifying prospect that the Sun was actually dying. Decades later it turned out that there was nothing wrong with the Sun at all. Rather, the particles were performing some trickery on their way to the Earth, fooling detectors into believing they'd gone missing.

Climate scientists may thus be about to learn what physicists have long recognised: that sometimes the more you find out, the less you know.

Robert Matthews is a visiting reader in Science at Aston University, Birmingham, England