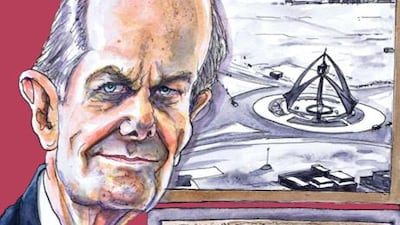

This Cambridge graduate has lived in the emirate on and off for decades, forming close ties through his legal work for merchant families. He helped in the setting up of Dubai Aluminium and the settlement of a border dispute between Dubai and Sharjah. Gillian Duncan reports

Christopher Dixon would be the first to admit that he comes from an unconventional family.

At age 17, when he already had one full and four half-siblings, he learnt about another brother.

And as an adult, the partner at the law firm Taylor Wessing Middle East, who has lived in the UAE on and off for decades, has continued to add to an extended family through close, long relationships with some of his clients.

"I have always done a lot of work for merchant families here. I was lucky enough in [the early] days to get to know some of them quite well, so I am treated like a member of the family," he says.

He has known one "paterfamilias", as he calls him, for about 35 years.

"He was one of the first people I met when I came to Dubai," he says. "My office was on Dubai Creek. I was in a four storey, a high building, and I looked down and his shop was there. I could see when he came out for tea, which he often did at about 4pm or 4.30pm, I would go down and join him."

Back then the patriarch, whom he declines to name, already had several shops. But he is now the head of a conglomerate. "He's always saying to everyone 'this is my lawyer, but my friend as well', which is lovely."

Mr Dixon spent most of his three years at Cambridge University studying classics, but after deciding that he did not want to be a politician or a teacher, the two options that the specialisation seemed to offer, he switched to law in his last year.

"I thought law would suit me," he says.

He did his articles - or training contract, as it is now called - with an established firm in London's Bloomsbury district.

After qualifying, he spotted an advertisement for a position with a legal firm that had an office in Dubai.

"I was always interested in going abroad, probably because I was born abroad," he adds.

He moved to Dubai in the mid-1970s, long before the emirate became home to the world's tallest building.

At the time the highest landmark in the city was probably the Clock Tower, he says, and only main roads were turfed.

A two-lane highway linked Dubai with the capital, and crossing camels continued to be a hazard into the 1980s.

"Architecturally, there were buildings on either side of the Creek and that was Dubai," he says.

Mr Dixon's arrival in the emirate coincided with the start of several major infrastructure projects. He was involved in the setting up of entities such as Dubai Aluminium (Dubal), Dubai Cable Company (Ducab) and the World Trade Centre.

But one of his most exciting tasks was a boundary dispute between Dubai and Sharjah.

In the 1950s, there were no demarcated boundaries. Instead, if tribes, particularly Bedouin, owed allegiance to a particular sheikh and always used a certain watering hole, it was shown as being part of the sheikh's territory.

But with the discovery of oil in the region, rulers started to become more conscious of boundaries.

In the 1970s, Dubai and Sharjah could not agree on their border. They agreed to refer the matter to arbitration, and the hearing lasted several years.

During the time, Mr Dixon moved back to the United Kingdom, but he continued to work on the case almost full-time, making regular trips to survey the landscape.

Using a handwritten map drawn up by Julian Walker, a British junior diplomatic officer, Mr Dixon and colleagues set out in a Land Rover to search for relevant features in the landscape.

"We would turn up at [the majlis of Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, the Ruler of Dubai at the time] at 5am, because he was a very early starter - we were quite privileged to be involved - he would basically, through one of his [aides] issue instructions for the day," he says.

Mr Dixon would identify an oasis that they would like to see and Sheikh Rashid would arrange for the various tribes that used the watering hole to provide the survey team with statements.

"At the end of the day, how do you establish that a particular part of territory belongs to Dubai or Sharjah? It is who uses it. That was one of the tests," he says.

Mr Dixon's second stint in Dubai was between 1982 and 1986. After that he moved back to the UK and managed Fox & Gibbons' London office for a time.

But he left the firm in 1996 to set up his own practice in Dubai with a partner.

"We set up a firm called Key and Dixon. That carried on for 11 years and we formed an association with our current masters, if you like, Taylor Wessing, in 2002, as an associate law firm," says Mr Dixon. The two firms merged in 2007.

Mr Dixon is looking to ease out over the next couple of years and will probably spend most of his time in Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, where he and his wife own a house.

"Have you heard about the Chipping Norton set?" he asks, referring to the group of powerful residents including David Cameron, the UK prime minister, and Rebekah Brooks, the former News International chief executive, who used to meet socially before the phone hacking scandal.

He is not a member of the set. But his previous tenants might have been, he says.

Mr Dixon's own roots are a long way from Chipping Norton, and closer to Dubai.

He was born in a small village in the foothills of the Himalayas in India, where his father worked in the civil service.

But when he was just 2 years old, tragedy struck with the sudden death of his mother.

His father decided to move back to England with his two children in 1947, shortly after India declared independence from Britain. They moved to Kings Langley, and when Mr Dixon was about 5, his father married again and had a further four children with his second wife, who treated all the siblings the same, says Mr Dixon.

Mr Dixon recalls seeing another child in family photographs from when he was young, but his father never told him - and it only came out when he was about 17 - that the boy was his half-brother, his mother's son from a previous marriage.

When Mr Dixon did find out, his father was "a bit apologetic", he says. "But he was very glad to see him. We actually saw quite a bit of him in that time, up until when my father died," adds Mr Dixon, who has stayed in touch with his half-brother.

Perhaps one day he might introduce him to his "paterfamilias" client in Dubai.

"It's a complicated family," he says.