The distinctive red livery of the Monzo debit card, usually in the hands of twentysomething consumers, became the hallmark of a rapidly changing banking scene in the UK.

That excitement is now set to ripple around the UAE with the announcement of its first independent digital bank last week.

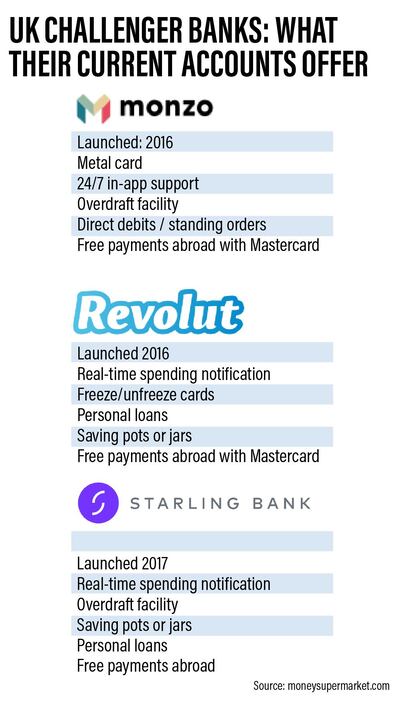

The entry of Monzo and Revolut into Britain’s consumer banking landscape in 2016 marked a step change from the offer of traditional banks reliant on customers using high street branches. The challengers relied on app platforms with customer support delivered through in-app chat.

Starling, another digital player, entered the marketplace a year later, with the challengers wowing customers with innovations, such as up-to-the minute spending notifications, commission-free spending abroad and the ability to instantly freeze and unfreeze cards.

Other features included bill splitting, saving pots or jars to help customers hit different savings targets, as well as instant PIN changes and even the ability to trade cryptocurrency.

For traditional banks, it was a wake-up call.

While banks had always relied on their ability to offer customers one-to-one support in their physical branches, the digital competition helped customers stay on top of their finances while also being able to adapt quickly to changing consumer needs.

"Every time established banks try to make innovations, it's got to fit in with this huge legacy of systems going back decades and decades," Andy Webb, founder of UK personal finance site Be Clever With Your Cash, told The National.

“But the new banks were starting from scratch. They could easily add new features on something that was designed for use on a phone, rather than adapted from older systems.”

Emirates NBD, Dubai's largest bank, was the first to enter the digital banking arena in the UAE with Liv. in February 2017.

The app allowed customers to open an instant account, track expenses, split bills with friends, share money using social media and benefit from discounts on eating out.

However, Zand, headed by Emaar Properties founder and former chairman Mohamed Alabbar, takes the concept one step further as it will operate independently of existing lenders.

With the bank set to cater for both retail and corporate clients, what can it learn from the rise of challenger banks in Britain?

Pandemic dents profits at UK's challenger banks

While the digital banks started out as the shining stars of Britain's financial technology industry, with customers even signing up for waiting lists to get their hands on Monzo's iconic metal card, the pandemic has changed that picture.

After years of investor enthusiasm that allowed them to focus on winning customers over profits, Covid forced the UK's three largest digital banks – Monzo, Starling and Revolut – to cut costs and hunt for new income streams.

Last year, Monzo’s losses rose to £113.8 million ($156.73) in the 12-month period ending February 2020, up from the £47.1m it lost in the previous period.

The business said slowing customer growth during the pandemic led to “material uncertainties”.

“With this unexpected change in landscape, we’ve seen organic customer growth slow as word of mouth drops, and we’ll see reductions in revenue and higher credit losses,” Tom Blomfield, president of Monzo, wrote in the company’s annual report.

While rising losses are expected in the start-up scene, as that is often how a new company grows, the issue for digital banks during the pandemic has been slowing day-to-day banking, after card transaction fees, particularly from foreign travel, dried up.

Revolut reported a drop in revenue of 40 per cent in April last year, with the company’s chief executive quickly focusing on cutting costs and improving the product.

“The result was, six or seven months in, we started to break even as a business,” Nikolay Storonsky, Revolut’s founder and chief executive said. “We cut costs, risk management improved significantly and we continued growing.”

It also launched its regulated banking service in 10 new countries and applied for another banking licence in the US, while Monzo and Starling raised fresh cash earlier this year to fund expansion.

Challenger banks fight back against Covid

While they are now fighting back from pandemic-induced losses, challenger banks need to prove to investors and customers that they are a viable, long-term banking solution.

“They are still trying to find that model that works for them. Monzo in particular has introduced different paid features, with the first one a complete failure that they scrapped quite soon afterwards,” Mr Webb said.

“Because we have this culture of free banking in the UK, it takes a lot for someone to pay money to get something else in exchange.”

Another challenge is that many customers in the UK do not use the digital banks for their main account.

“So they don't necessarily have all their money sitting in there,” Mr Webb said.

“A normal bank has a lot of customers with a lot of money being saved and they are used far more regularly as a main bank account, so the money is sitting there and they can use that to lend out or invest. While Monzo and Starling do that too, they don't have that same scale.”

Traditional lenders have also upped their game

Traditional lenders welcomed the glitches the challengers faced during the pandemic, giving them the opportunity to promote the security and human interaction that high street banks offer when customers face complicated issues or need specific financial guidance.

They fought hard to catch up with their innovative rivals, upgrading their online channels and offering apps with all the bells and whistles expected from their digital-only rivals.

“They are absolutely trying to up their game, some with more success than others,” Mr Webb said. “A lot of the features that we saw first on the likes of Monzo and Starling, such as separate savings spaces and pots, the other banks are offering that too and they need to,” said Mr Webb.

“For the challenger banks, however, the question is – what do they do next when the other banks catch up?”

What's next for the challenger banks?

Alex Nicolaus, the head of people and culture at global FinTech company Paysend – the first of its kind to offer card-to-card transactions – said digital banks needed to diversify their service to offer more than just pure banking.

He highlighted the example of Grab, a Singapore-based technology company that offers ride-hailing transport services, food delivery and payments in one place.

"Their success is very much around the super app, where you combine everything from banking, to food delivery, to ride hailing – any touchpoint someone has from their day to day," Mr Nicolaus told The National.

“Everybody has a bank account, and everybody needs money transfers or savings but you need to diversify into other areas, so you want one app that allows you to do multiple things, aside from just banking and transfers … such as payments for other services in terms of transport, holiday bookings or food delivery.”

While digital banks in the UK have struggled financially during the pandemic, they are on the rise worldwide.

"The pandemic has forced consumers, by not being able to use the normal banking services as they would, to adopt what was already there," said Mr Nicolaus, who is also the author of Startup Culture: Your Superpower for Sustainable Growth, published this month.

“What you've seen in Europe, specifically, as well as south-east Asia, is that being at home, the trust level really increased. Consumers have the confidence and the agility to start using those services now.”

UK lenders close branches amid falling demand

Covid-19 has certainly not been kind to traditional lenders, with many choosing to close high street branches amid dwindling demand during the pandemic.

Last month, Santander said it would close 111 branches across the UK – a fifth of its network – in response to the shift to digital banking, accelerated by the pandemic, with HSBC also shutting another 82 branches this year.

Meanwhile, state-backed UK bank NatWest said it would overhaul its retail banking business to fight back against FinTech rivals and increase revenue.

The bank, which operates about 16 per cent of UK personal current accounts and struggled to sell off its retail business in Ireland, will make staff available for longer hours so that customers can talk to human bankers – a move designed to rival digital banks’ app chat option.

Other conventional lenders looking to take on the challengers include American bank JP Morgan, which plans to launch its own digital bank in the UK, based in Canary Wharf, London.

It is the second major US lender to enter the UK retail banking market, with Goldman Sachs unveiling its Marcus-branded digital savings accounts in 2018.

“With enough time and money most companies can copy what the challenger banks do, so the big commercial and retail banks will catch up,” Mr Nicolaus said.

“My advice for digital banks is to try to be one step ahead and understand what the next consumer integration or trend would be in order to solve those problems.”

Looking ahead, he believes the opportunities lie in banking for small-to-medium enterprises, an area into which Starling has already moved.

While it started out as an app-based current account for consumers, it pivoted towards a service for small businesses, lending more than £2bn to date.

“That is still an area where a lot of the challenger banks are going to go next. The business-to-consumer segment has been commoditised and everybody is pretty much offering the same,” Mr Nicolaus.

“With the pandemic, a lot of individuals have lost their jobs or been furloughed and started businesses online. And because there's less mobility as well, there's going to be a rise in transactions. There will be a real race to try to be ahead on the business-to-business banking side.”

More on digital banking

Central Bank of the UAE grants licence to new digital bank

FinTech matchmaker: TISAtech recruits UAE start-ups looking to expand to Britain

Now Money: a fintech start-up servicing the UAE's low-income migrant population