Investors poured money into artificial intelligence-focused companies at a historic rate during the pandemic and technology rivals the US and China have reached “peer” status in AI development, according to a new study from Stanford University.

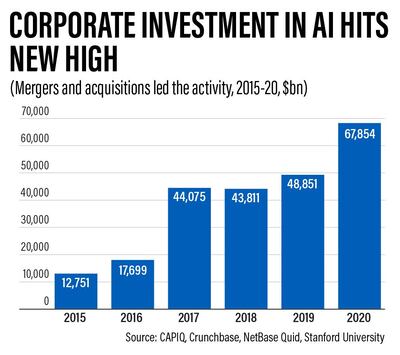

Total global AI investment, including private investment, public offerings, mergers and acquisitions and minority stakes, increased by 40 per cent in 2020 for a total of $67.9 billion, compared with a 12 per cent jump from 2018 to 2019.

“It’s clear from the data that, in 2020, AI started to have a more significant impact on the world, while the technology continued to evolve very rapidly,” said Jack Clark, a co-chair of the university’s AI Index.

“[Our] analysis shows that the US and China have become peer nations with one another on AI development.”

The 2021 AI Index is the fourth annual study of the impact and progress AI is making globally and is developed by an interdisciplinary team at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence in partnership with organisations from industry, academia and government.

Big pharma

The biggest area of activity for investors was in M&As. The sector that received the most funding in 2020 was, not surprisingly, in drug discovery and molecular biology, with more than $13.8bn, according to the index.

“The biggest increases were in health care and pharma, where four times as many people increased their investments as decreased them,” said Erik Brynjolfsson, a senior fellow at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI) and director of the Stanford Digital Economy Lab.

He noted that some of those applications led to breakthroughs in addressing the pandemic.

“One of the reasons we had a vaccine in record time was these technologies allowed us to analyse protein structures much more rapidly. We'll be seeing a lot more of that.”

China vs US

In 2020, China surpassed the US in significant scholarly work.

Chinese-affiliated scholars were cited in more peer-reviewed journals than any other country’s scholars, indicating China’s AI research has increased in quality and quantity, according to the index.

However, the US has more cited AI conference papers than China over the past decade.

The US also for the first time recorded a decline in hiring in the field of AI.

The index attributed this to two possibilities: slowing growth due to the pandemic or a sign of maturity in the AI labour market.

Diversity doldrums

Diversity remains a pressing issue in the field worldwide. AI is still predominantly male and lacking in diversity when it comes to race and ethnicity.

Women made up less than 1 in 5 of all AI and computer science PhD graduates in North America over the past 10 years. In 2019, 45 per cent of new US-resident AI PhD graduates were white, while 2.4 per cent were African American and 3.2 per cent were Hispanic.

“It’s not necessarily surprising that the needle hasn’t moved, unfortunately, because that’s been the case for several years,” said Terah Lyons, a 2021 AI Index steering committee member and executive director of the non-profit Partnership on AI. “It’s clear that more attention needs to be paid, and things need to be done differently.”

However, there were signs of progress on gender parity in several countries: women overtook men in gaining AI skills in India, South Korea, Singapore and Australia in 2020.

Deepfakes – and ethics – on the rise

Stanford found that deepfakes (the industry term is synthetic media) are on the rise, with synthetic text, imagery and video “demonstrating the progress of AI but also highlighting the potential for unethical or dangerous use”.

To that end, AI researchers are increasingly grappling with the ethical challenges arising in this nascent field. The index recorded a significant increase in papers mentioning ethics and related keywords between 2001 and 2020, from fewer than 20 at the start of the century to nearly 70 last year.

Looking ahead

AI is expected to expand across industries and beyond immediate needs related to the pandemic. While investors in fields such as car manufacturers and financial services were quick to adopt AI, Stanford researchers said 2020 was a pivotal year for less tech-focused industries, functions and geographies to begin using AI.

“It’s not that you just buy the technology and slap it in,” Mr Brynjolfsson said. “You need to do business process changes. That's been a hindrance to rapid adoption of AI, even though Covid has pushed companies to be more aggressive about it.”