The euro's crossing of a psychological threshold last week, when it briefly hit parity with the US dollar for the first time in 20 years, may reverberate economically across some of its closest trading partners.

The slide in the currency came amid growing concerns about the energy crisis in Europe and soaring inflation, which could trigger a recession, as well as a bullish outlook for the US currency.

The euro has since recovered and rose briefly on Thursday after the European Central Bank raised interest rates for the first time in 11 years by 50 basis points in a move to fight inflation, which rose to a record high of 8.6 per cent in June.

It was trading at 1.018 to the dollar at 6.44 pm UAE time on Thursday, after rising to 1.025 following the ECB's announcement.

But concerns remain.

“The ECB will continue to tread a fine line between tightening monetary policy to address inflation while ensuring that countries with high debt-to-GDP [gross domestic product] ratios do not experience unsustainably high interest rates,” says Christopher Payne, chief economist at Dubai-based Peninsula Real Estate.

“This is a very tricky task for the ECB but they have no alternative. In my view, they would rather see inflation run on a bit longer and a bit higher than threaten a full-blown euro debt crisis.”

The EU is also continuing to grapple with a looming energy crisis amid gas supply concerns from Russia as it tackles an unusually hot summer and prepares for the winter months.

Unchecked inflation or a full-blown energy crisis could lead to a recession, which will add pressure on the euro.

How will the euro crisis affect the Arab region?

Arab economies have traditionally strong connections with Europe, with North African countries, in particular, heavily dependent on the EU for trade and tourism.

The EU serves as the largest trading partner of Tunisia (accounting for 57.9 per cent of its trade in 2020), Morocco (56 per cent in 2019), Algeria (46.7 per cent in 2019) and Egypt (24.5 per cent in 2020), according to data from the European Commission.

While exports to the EU from Tunisia and Morocco focus on textiles and agricultural products — Morocco is one of the Europe's biggest source markets for tomatoes — fuels and mining products lead exports from Algeria and Egypt.

Meanwhile, North African countries are mainly reliant on the bloc for machinery, transport equipment and chemicals.

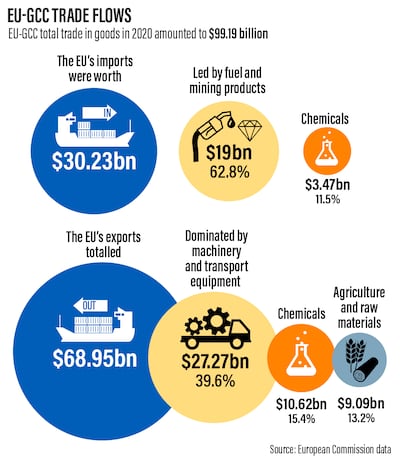

The GCC also shares close economic and geopolitical ties with the EU, its second-biggest trade partner after China.

The EU accounted for 12.3 per cent of the Gulf region's total goods trade in 2020, according to European Commission data. While 17.8 per cent of the GCC’s imports came from the EU in 2020, 6.9 per cent of the Gulf region's exports went to the union.

For the moment, the euro's fluctuation has limited effects on the Mena region, since some countries, particularly those in North Africa, have their currencies pegged to a basket of major currencies dominated by the euro, which offers them buffer from the decline to a certain extent, says Wael Makarem, senior market strategist for the Mena at currency broker Exness.

For some of these countries, the relative decline of the euro could have an impact on the competitiveness of local companies since their products would become more expensive in international markets, he says.

“For Morocco and Tunisia, agricultural and textile exports are the most exposed, although their currencies are mainly pegged to the euro, reducing risks. Algeria, on the other hand, is less exposed as it mainly exports oil and gas and could benefit from less expensive imports,” Mr Makarem says.

“However, the Arab region remains exposed to the eurozone’s economic slowdown and the secondary effects of the war in Ukraine such as agricultural and energy price increases.”

Commodity prices shot up worldwide after Russia invaded Ukraine in late February. The two nations are major international suppliers of wheat and fertilisers, and the conflict has pushed up food prices globally.

Meanwhile, western sanctions on Russia, the world's second-biggest exporter of crude, have also led to a surge in oil prices this year amid supply concerns.

The impact of the current euro crisis on the Arab region will be “mixed”, says Monica Malik, chief economist at Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank.

“A number of Mena commodity importers are already negatively impacted by the higher food and energy costs. The deteriorating outlook for the eurozone and the weakness in the euro will likely have a greater effect on areas such as travel and tourism going forward,” she says.

The EU is a key inbound and outbound tourism market for Arab countries.

The number of tourists from Europe to the GCC is expected to hit 13.3 million by 2024, increasing at a compound annual growth rate of 17.5 per cent from 2021, according to analytics company GlobalData.

Meanwhile, visitors from the Gulf also flock to European destinations such as Switzerland, France and Italy, especially during the summer months.

“Obviously, for those travelling to the eurozone from the Gulf, a weaker currency is beneficial,” says Mr Payne.

“But net-net, a weak euro caused by higher inflation is likely to signify weak demand, which will reduce demand for oil,” he says.

This, in turn, could affect energy exporters in the Arab region.

From an energy perspective, European countries are rapidly looking to diversify their supplies away from Moscow and plan to wean themselves off Russian oil imports by the end of the year as part of sanctions imposed in response to the Ukraine war.

The EU is also looking for alternate sources for gas amid concerns that Moscow could suddenly stop its supplies.

While Russian President Vladimir Putin confirmed that gas flows to Europe will be restored via the Nord Stream 1 pipeline on Thursday, after a 10-day shutdown for maintenance, he also issued a warning that supplies would be tightly curbed until the problems with the sanctioned turbine parts are resolved.

“The Mena region will be important for Europe as its look to diversify its energy sources — not only the GCC but also Egypt for gas,” says Ms Malik.

Last month, the EU signed an agreement with Egypt and Israel to boost gas exports to Europe.

In the first six months of this year, more than 72 per cent of Egypt’s liquefied natural gas exports went to Europe, compared with 29 per cent for the entire 2021 calendar year, Refinitiv LNG flows data shows.

“It will take time for the eurozone to diversify its energy imports. We see relations with the Mena region strengthening as Europe looks to reduce its dependence on Russian energy,” Ms Malik says.

What next?

There are many factors in play regarding the value of the euro.

With the ECB embracing a tighter monetary policy, this could reduce the differential with interest rates in the US, diminishing the incentives for investors to move capital to the US, Mr Makarem says.

“The ECB’s capacity to tame inflation could also play an important role along with its ability to keep economic growth stable. Ukraine remains another factor that is beyond control,” he says.

“For the Mena region, a compression of trade could take place to a certain extent as long as the eurozone remains under pressure.”

Significant economic uncertainty remains for the eurozone, mainly from the energy side, says Ms Malik.

The main risk is if there is a full-blown energy crisis. A weaker euro will add to energy price inflation in Europe and to upward inflationary pressures, she says.

“This would result in gas rationing and a fall in industrial output, which, in turn, would curtail eurozone exports and add to global supply chain disruptions,” she says.

Mr Payne says a likely scenario is a period of stagflation in the eurozone and continued weakness of the euro.

“The upshot of this is lower domestic demand, which will affect exporting countries such as Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria. Weaker demand from Europe, combined with a weaker euro, will also likely take the pressure out of the oil market, leading to lower prices. Although outside of a crisis scenario, we would still expect oil prices to remain above $80 a barrel, given the war in Ukraine.”