In cooler months, people gather at the weekend to fish along the shoreline under Al Maqta Bridge in Abu Dhabi. They sit on foldable chairs, watching the streetlights splay in the still waters of the inlet to the creek. They chat, smoke shisha and wait for their fishing rods to twitch.

On Friday afternoons, yoga mats unfurl on the grass at Umm Al Emarat Park for a class that is dozens strong. A stone’s throw away, a group of teenagers jeer and cheer as a football rolls between the two backpacks they’ve designated as goal posts.

From 5pm onwards, some car parks across Abu Dhabi double up as cricket stadiums. Matches are held across age groups and friendships are soldered and tested. As one game becomes heated and a child threatens to take his cricket ball and go home, a man sits down on one of the polished boulders behind the Crowne Plaza, uncaps a plastic bowl and eats his dinner.

Every city has its unique way of being affected by its population; of being transformed by it. The most conspicuous markers of these effects can probably be found in a city’s public spaces, and not only its formal ones, such as parks, but its informal ones, such as car parks.

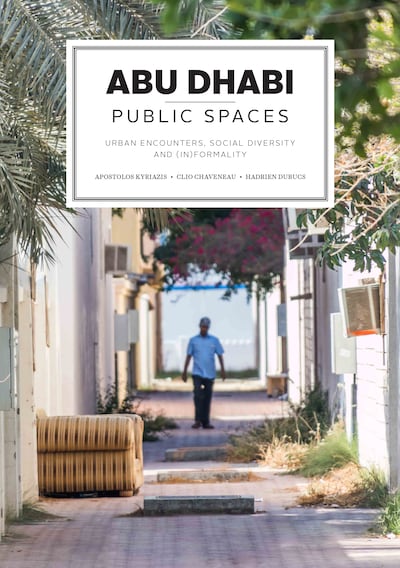

Abu Dhabi Public Spaces examines this, providing an insight into urban life in the capital in a way you’re not likely to find in any travel book dedicated to the emirate. The book was written by a multidisciplinary team of academics, including sociologist Clio Chaveneau, geographer Hadrien Dubucs and architect Apostolos Kyriazis, and was published this year by Motivate Media Group, with the support of Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi.

The book is a must-read not only for visitors who want to discover Abu Dhabi beyond its tourist attractions, but also for those who have lived in the city for years and who are familiar with the spaces written about. It is comprehensive, with photographs as well as maps of pedestrian networks and building heights, and it features 14 locations around the city, including the undeveloped Shabiya plot, where cricket and volleyball games are often played, Al Maqta Bridge and Family Park on the Corniche.

“We were living in the city for several years when we started the project [in 2018],” says Kyriazis, an assistant professor at Abu Dhabi University.

“Abu Dhabi, the way it was designed and constructed in the past 50 years, has specific layers easy to read for academics. We categorised areas into groups that are distinguishable with specific building types, timing of development and demographic.”

This categorisation was how the authors segmented the city into seven regions. In each, they aimed to find a formal public space and an informal one.

For instance, the section dedicated to the suburbs of Al Shamkha lists Al Shamkha Park 4 as the area’s most noteworthy public space, mostly for its football pitch. For its informal spot, the authors chose Al Khayr Street, where local vendors sell hay and firewood. The area is now also bustling with fast-food trucks.

“It is a trend that takes advantage of the high degree of mobility of the business unit [the truck] and the prevailing automobile culture,” the book states. “Within those ad-hoc generated drive-through areas, other informal activities – related to the youth’s socialising behaviour takes place.”

For Khalifa City, the authors picked Khalifa Park 3 as the area's formal space, noting its basketball court and open area, and the pink shops, named for the colour of the buildings, as its informal spot. The shops lay in front of a large undeveloped plot, which thrives with activity. The writers say, in the book, “The undeveloped lot temporarily hosts a mosque and a small kiosk of the Red Crescent, but it is also converted into a vast public space for pick-up trucks, food deliverers and even municipality garbage trucks.”

With the help of a team of research assistants, the authors carried out observations from January 2018 to December 2019, studying the urban morphology of selected areas, taking photographs and identifying the public spaces they wanted to include in the book.

Formal public spaces in Abu Dhabi are easy to spot, as they are clearly mapped out and are specifically designed to fulfil that function. With informal ones, however, it gets a little more challenging.

“They are never the same,” Kyriazis says. “They are changing throughout the day, throughout the seasons and the years. Some disappear, some come back up again, some show up randomly, sometimes you stumble on one by chance. Working on the formal spaces was easy, with the informal ones we have to continuously adapt and keep changing decisions.”

Chaveneau, an assistant professor at Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi, says readers should keep the mercurial nature of public spaces in mind when going through the book.

“It’s interesting to take this book and research as a kind of specific moment of Abu Dhabi, a snapshot,” she says. She goes on to say that a city’s public spaces are continuously shifting. When the team began the project, they struggled to find spaces to include from Reem Island. Today, the area has plenty.

“When we first started this project, we just found this playground next to Boutik Mall. Families living around the area were either going to the Corniche, to Umm Al Emarat or to this tiny place. Even for informal spaces, we struggled. We'd pick one and then it closes down and becomes inaccessible to the public. When we look at Reem Island now, you have Reem Central Park, which is huge. You have the waterfront walk, canals and I think more is going to develop in this area.”

Dubucs, also an associate professor at Sorbonne University Abu Dhabi, says given how the book reflects upon the city’s urban fabric as it exists in the present, he considers how it will be reflected on several years from now. “Kind of like the way we reflect on public spaces of the 1970s and 1980s today,” he says.

Umm Al Emarat Park, he says, is one barometer of change in the way public spaces are perceived in the emirate. The park, which opened in 1982, first served as a family and female-only space, before a series of developments dramatically changed it into what it is today, with a 1,200-metre-long running track, an amphitheatre and an outdoor space for movie and sports screenings.

With its clear, accessible prose and small form, Abu Dhabi Public Spaces is the perfect companion to help you familiarise yourself with the city, whether you’ve just flown in or are a long-time resident.

“When we were discussing the book with publishers we noted that this was not strictly an academic title,” Kyriazis says. “It’s also designed for travellers, tourists and people who live here who have not been lucky enough to learn the city; to walk around the city. It is a little push for exploration and discovery.”