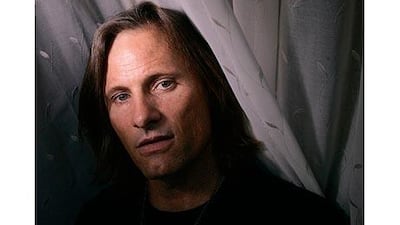

Actor, poet, painter, publisher - Viggo Mortensen has never been one to be typecast. Now, he has turned his back on Hollywood blockbusters for a haunting screen version of Cormac McCarthy's post-apocalyptic novel, The Road. He talks to Ali Jaafar about life and identity. Viggo Mortensen picks at a sandwich with one hand while flicking his shoulder-length hair with the other as a cigarette burns close by. He is in London to promote his latest film, director John Hillcoat's haunting adaptation of Cormac McCarthy's post-apocalyptic masterpiece The Road in which he plays "the man". His T-shirt, emblazoned with the words "Make Art, Not War", is a fitting summation of Mortensen, even if the 51-year-old defies easy classification. An actor, poet, painter, photographer, musician - in recent years he's even dabbled as a publisher - Mortensen has carved a unique position for himself.

Blessed with sinewy, chiselled good looks, and having starred in The Lord Of The Rings trilogy, some of the highest-grossing films in the history of cinema, Mortensen could easily have built a career playing classic Hollywood leading men. Instead, he has frequently chosen more challenging roles, often playing characters on some kind of existential journey in search of redemption. "Generally, those characters are in good stories," he says. "Those stories where there is some kind of journey, there is also a learning experience. It's the same with making movies. Every movie, whether it turns out well or not, is a journey where you make friends and learn something about yourself." The same is true of his character in The Road. McCarthy's novel, written in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks in the United States, follows a father and son - known only as "the man" and "the boy" - as they walk alone through a desolate, scorched America inhabited by gangs of cannibals. As they travel through the wasteland - filmed partly in Pennsylvania and New Orleans - towards the coast in search of an idealised promised land to escape from the horrors around them, we see the two characters gradually taking on each other's responsibilities; the son becomes father to the man and vice versa. Mortensen masterfully captures his character's disintegration from gun-toting survivalist to grief-stricken wounded soul struggling to find hope in the barren landscape. In many ways, the role is tailor-made for Mortensen's ability to veer between the muscular physical action he displayed in The Lord Of The Rings trilogy and his more insular, character studies in the likes of Sean Penn's The Indian Runner and David Cronenberg's The History of Violence.

"For some actors it might be a stretch that they're so tender and sensitive to a child and yet be able to physically do what he has to do in the film," says Hillcoat. "Viggo's very intense and wound up, and that is what the father is all about. He's so haunted by the suicide of his wife and yet he has this incredible protective relationship with his son. It's a love story and in such a challenging and extreme survival world, he has to do things that have to be credible."

Mortensen's background is as exotic as any of the characters he has portrayed on the screen. Born in New York's Lower East Side to a Danish father and an American mother, he was raised on cattle and chicken ranches in Venezuela and Argentina. After his parents divorced, Mortensen moved with his mother and two brothers to live in upstate New York. By the time he was 11, he could already speak four languages. As a young man he worked in flower markets and as a trucker in Denmark, before returning to New York where he worked as a waiter and barman. It was there that he enrolled in the Warren Robertson Theatre Workshop to try his luck as an actor.

A series of supporting roles in the mid-1990s, notably opposite Al Pacino in Carlito's Way and Denzel Washington in Crimson Tide as well as a scene-stealing performance in Sean Penn's directorial debut The Indian Runner raised his profile in Hollywood before he landed the plum role of Aragorn in Peter Jackson's epic adaptation of The Lord Of The Rings. Regardless of the size of the productions he works on, though, he makes a point of dedicating himself entirely to the role at hand. In 1995's The Passion Of Darkly Noon, for example, where his character was a mute, the actor refused to speak for the entire four-week shoot.

"Whether it's a tiny movie you shoot in a week, or a 10-minute short or a big epic adventure, it doesn't make any difference to me," he says. "Whether a film like The Lord Of The Rings or The Road, it still remains all about what's going on with the relationships of the characters. The scale of a project doesn't make a huge difference. When everything's going well with shooting you don't notice anything. When it's going badly, though, that's when you suddenly notice everything, you start feeling under pressure and it gets distracting. That's when you want to erase everything and start again."

That notion of starting again is a recurring motif throughout Mortensen's work, most recently in The Road but also in films such as David Cronenberg's The History of Violence where he plays a cold-blooded gangster reinventing himself in small-town America. That transient theme of identity is something Mortensen has transposed to his life. As well as being an actor, he has also developed fruitful sidelines as a poet, photographer and musician. In 2002, using some of the money he earned from his roles in The Lord Of The Rings trilogy, he launched his own publishing house, Perceval Press, specialising in Latin American writers.

Mortensen's own writing also plays with the fragility of love and life. In 1993 he published his first collection of poetry Ten Last Night. That was followed with Recent Forgeries in 1998, which included examples of his photography and music. Other multimedia publications include Errant Vine, a limited-edition booklet of an exhibit of his work held at the Roger Mann Gallery, Hole In The Sun, a collection of colour and black and white photographs he had taken of someone's swimming pool, and Coincidence Of Memory, published in 2002, which collected a variety of his musings over two decades dating back to 1978.

One poem from Recent Forgeries collection sees the peripatetic traveller in a particularly wistful mood. She told me she was in love, and that she just wanted to enjoy it for as long as it lasted. That she didn't want to judge the feeling, compare it to other times with other partners. There was nothing gained from analysing, she said - all it did was rob you of time better spent in those new arms. There wasn't anything for me to say.

"He's a lovely guy and is more of an artist than simply an actor. He could almost be a yogi," says Omar Sharif, who co-starred with Mortensen in Hidalgo in 2003. "He was doing all these interviews for The Two Towers while we were shooting together wearing a T-shirt which read 'No Blood for Oil.' It was around the time that the war in Iraq was about to start and the producers were worried it might cause resentment in America. He's just a very simple guy with simple tastes. I would try to get him to have a decent meal and he would just sit there nibbling on a piece of lettuce, which upset me no end."

While Mortensen has never shied away from voicing his political opinions, his anti-establishment streak has never got in the way of his primary interest, namely artistic exploration. He reportedly refused to wear an academic gown at his commencement from St Lawrence University in New York, where he had studied Spanish, because they had been produced in a sweatshop. In person, Mortensen is a similarly curious mix of reticence and openness. His personal life, though obviously a substantial influence on his career and choice of rules, remains largely off limits. He has been married before, to Exene Cervanka, a singer with the punk group X. Although now divorced, Mortensen remains close to her. The couple have a 22-year-old son, Henry Blake Mortensen, who has worked with his father on his various cultural endeavours, including performing poetry recitals with him. But along with this serious side, Mortensen is prone to amusing digressions and flashes of humour. When asked about his next project, he quips, "We're doing The Road Part 2: The Resurrection."

He is also consciously attentive to those around him. Throughout our interview, he makes a concerted effort to check on the welfare of Kodi Smit-McPhee, his young co-star in The Road. The film stands or falls on the chemistry between their two characters, and Mortensen developed a close relationship with 13-year-old Smit-McPhee. In one particularly affecting scene, the pair bathe in an icy lake.

In reality, the jarring coldness of the water left Smit-McPhee in tears of pain. Rather than ending the scene, however, Mortensen cradled the young boy in his arms as the two wept together. "It's our job to look that tired and hungry but looking that cold wasn't too difficult," says Mortensen. "It was one of those moments that actually could have gone different ways, but when I pulled Kodi's head out of the water on the second take he was almost in shock. I didn't realise how much it had upset him until I looked right into his eyes, right in the middle of the take. He called me Papa and he's crying for real but he played the scene. That day, it was almost like something broke and expanded inside him as an actor. It really cemented our relationship."

And with that, Mortensen is off to another set of interviews. He has repeatedly threatened to give up making films so he can concentrate on his stage work and publishing. He had been set to perform in the Ariel Dorfman play Purgotario in Madrid, but pulled out two weeks ago because of his mother's ill health. He is also due to release a new book of poems. In the meantime, he has to do the awards season publicity circuit for The Road.

Despite an Academy Award nomination for Cronenberg's Eastern Promises, in which he famously bared all during a vicious, nude fight scene, the actor's mantelpiece is still relatively bare of awards. There has been awards buzz over his performance in The Road, though Mortensen is a deft hand at playing down the hype. "I used to be much more nervous about all this stuff but I've had some practice at it now," he says. "The key is just to be honest and be yourself."