London-based journalist Tony Barrell has often been drawn to some rather recherché topics. Having previously written about The Roswell UFO incident, the celebrity look-alike industry, urban myths and lucid dreamers and battle re-enactors, he now turns his attention to that most marginalised and misunderstood of species, the drummer.

Barrell isn’t a drummer himself, but he has great affection and respect for those who wield the sticks. He portrays them – not unreasonably – as unsung heroes with more responsibility on stage than is generally acknowledged: “The sweat pouring down your face is partly the result of physical exertion required to play your instrument”, he writes, “and partly the result of a profound terror that you are going to screw up.”

Barrell reminds us that the tricky business of solid drumming is central to the efficacy of any band, and yet, the author notes, drummers are often fall guys; a breed subject to digs about their intelligence and/or social skills. It’s a point that’s disarmingly underlined by the book’s healthy quotient of drummer jokes, many of which Barrell gets directly from drummers themselves. Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason, for example, tells the author this two-liner:

Child: “Mummy, when I grow up I want to be a drummer.”

Mother: “Don’t be ridiculous, darling – you can’t do both.”

Mason is one of 40 or so drummers Barrell interviews for his book. Other notable players he talks to include Phil Collins, who tells of how he made his peace with drum machines, Clem Burke of Blondie, and Prince’s former drummer Sheila E, a musician of whom, with tongue firmly in cheek, The Purple One liked to remark “Not bad – for a girl!”

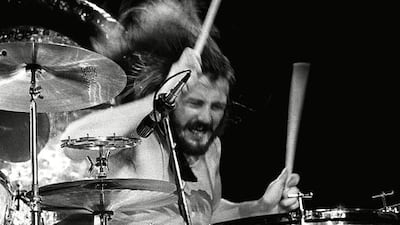

The book’s opening chapter, Into the Asylum, is largely an exploration – and thankfully ultimately a refutation – of the commonly-held notion that all drummers are in some way deranged. Consequently, it also gives Barrell the chance to trot out certain fairly well-worn anecdotes documenting the hell-raising behaviour of drummers such as The Who’s Keith Moon, Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham and Dennis Wilson of The Beach Boys.

It's a section that feels just a little misjudged, Barrell moving too quickly between fairly comic social transgressions and appalling incidents such as that in which an inebriated John Bonham punched a female record-company employee because she looked at him the "wrong" way. Similarly, while it's clearly not wrong, per se, to mention Animal, the wild-man puppet drummer from The Muppets in the same chapter as you tell the story of Jim Gordon, the famed session drummer and paranoid schizophrenic who committed matricide after hearing voices, you should perhaps handle the transitions and scattershot feed of information just a little more carefully than Barrell does here.

He is better on the drummer as de facto court jester (Ringo Starr; Micky Dolenz), and I am indebted to Barrell for alerting me to US comedian Fred Armisen's funny spoof series Complicated Drum Technique, wherein Armisen plays Jens Hannemann, "a supposed virtuoso who gives earnest and utterly ridiculous video drum tutorials that smartly parody the educational clips of drum teachers that proliferate on the Internet".

Still, just when you are warming to Barrell, he disappoints again by reporting upon, but not condemning, Iron Maiden drummer Nico McBrain’s racist jokes. Perhaps in saying nothing he is simply letting McBrain hoist himself on his own petard.

Further in, Barrell feels he must debunk the notion that drummers are a uniformly working-class breed. Stuart Copeland of The Police and Max Weinberg, timekeeper with Bruce Springsteen’s E Street Band, both from decidedly non-blue-collar stock, are cited as contradictory examples, but the point feels moot; one that didn’t need proving.

There’s some fun digression on how various drummers got their nicknames (tired of his endless fills, Rod Stewart dubbed Carmine Appice “The Dentist”). The much-loved – and much-derided – art of the drum solo is explored, too, with Barrell blaming its “image problem” on the kind of gig reviewer who portrays any drum solo as the juncture for discerning punters to repair to the bar.

Whether it be the solo spot of Mötley Crüe’s Tommy Lee (actually more hydraulics and pyrotechnics than anything else), or the dazzlingly purist drum battles contested by jazz greats Gene Krupa and Buddy Rich in the mid-1960s, however, Barrell makes a strong case for the drummer as loveably flamboyant showman; the person who works hardest for the audience’s applause. They are “the panel-beaters of rock ’n’ roll”, he remarks.

While Born to Drum has an annoying habit of stating the crushingly obvious – "There is no law that says you have to be male to be a drummer", says Barrell in a chapter about female players, it undoubtedly improves as it progresses. Barrell takes the rather dry topic of recording drums and makes it entertaining, recounting how, mindful that David Bowie drummer Woody Woodmansey had complained of his drums sounding "boxy" on Hunky Dory, the album's producer Ken Scott jokingly assembled Woody a kit comprised of Corn Flakes packets when they reconvened to begin work on Bowie's next album.

Elsewhere, a chapter titled The Worst Job in the World reads like a roll call of drumming injuries, detailing everything from the blisters Starr audibly complains of on The Beatles' Helter Skelter, to the "nice little spray of blood" that Elbow's drummer Richard Jupp produces each time he catches his knuckles on the edge of a cymbal.

We slowly become aware that Barrell is increasing our respect for drummers – never more so than when telling the story of how Def Leppard’s Rick Allen managed to overcome the loss of his left arm in a car accident, using a custom-built electronic kit and performing live again just 20 months later.

The potted history of drumming Barrell provides in his chapter The Beginning of Time, is well researched and informative. He explores the role of drummers who played at the 1793 execution of Louis XVI during the French Revolution, ponders the origins of the drum kit, and muses upon the relationship between drumming and tap dancing.

There’s a slight novelty aspect to the book’s next two chapters.

From Iggy Pop to Vogue cover star Cara Delevingne to celebrity chef Jamie Oliver, Secret Drummers flushes out those who started out behind the kit and ended up doing something else, while in a chapter exploring the sex appeal of drummers, Barrell quotes one dating agency rep thus: "Ladies stereotypically fancy the [group's] front man, but they [are] often more interested in themselves. Drummers are used to being pushed aside and are therefore way more interested [in their date] without a need to boost their ego."

Like a good but not particularly great drummer, Barrell occasionally loses his groove, and is sometimes more gratuitous fill-in than solid beat. When, in crushingly obvious mode again, he begins his final chapter, “Drummers are everywhere. There are certainly thousands and possibly millions of these people…”, you want to hit him over the head with a gong.

That said, Born to Drum is thoroughly entertaining; the kind of book that's great fun to dip into. And if its chief aim is to make us think differently about those who hit things with sticks, job done.

James McNair writes for Mojo magazine and The Independent.

thereview@thenational.ae