British and French colonialists drew the borders of the modern Middle East. It is this dispensation that is collapsing today in Iraq and Syria. But history could have taken a different course.

When the Ottoman Empire collapsed, a group of Arab soldiers fought to establish an Arab state in the area that was to become Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Lebanon and Israel/Palestine. The story of their resistance to European imperialism is barely known in the West. And their defeat by colonial armies helps explain the tragedy that is now playing out in Syria and Iraq.

Last year marked the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Sykes-Picot agreement, the secret territorial blueprint that Britain and France would impose on the Arab Middle East following the Ottoman Empire’s defeat in 1918.

Few in Europe and North America are familiar with Mark Sykes or Georges Picot, but the pact the two men signed is infamous throughout the Eastern Arab world.

Recently, ISIL has invoked Sykes-Picot as a symbol of western interference in Arab and Muslim affairs. When ISIL fighters tore down a border post between Iraq and Syria, they proclaimed that they were destroying the “Sykes-Picot fence”.

There is much talk today about the long-term effects of these cartographic incisions. If the mapmakers’ surgery had been more precise, would the region have suffered so much turmoil? Would Syria have collapsed into civil war, if a separate Alavi enclave had been created alongside a Sunni one? Was Iraq doomed from the start, since it should have been divided into three individual states, one Sunni, one Shiite, and one Kurdish?

Questions like these ignore the alternative future that many Arabs struggled for in the 1920s and 1930s: a single Arab state that would encompass the lands that became today's Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Israel/Palestine, and Lebanon. In the West, what most people know about the Arabs in the First World War is that a charismatic British officer T E Lawrence persuaded them to join the British campaign against the Ottomans, an account made famous by David Lean's 1962 movie Lawrence of Arabia. But the more important story about the Arabs in the First World War – the story that is not retold in a Hollywood blockbuster – is that the majority of Arab soldiers and officers stayed loyal to the Ottoman army and fought hard to defend the Ottoman state against British and French occupation.

After the Ottoman army disbanded in late 1918, Turkish soldiers and officers used what was left of the Ottoman army’s equipment to battle against the European occupation of parts of Anatolia for four more years. This four-year war – the Turkish War of Independence – was in fact the continuation of the First World War in Anatolia. The Turks’ ultimate victory against the Europeans resulted in the establishment of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 under the presidency of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk.

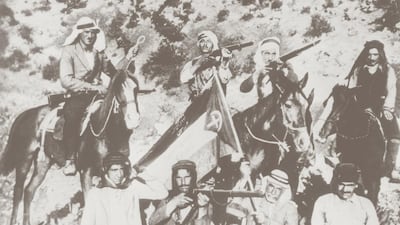

Inspired by these events, ex-Ottoman Arab officers led a series of rebellions against European occupation of the Arab lands south of Anatolia, in Greater Syria (today Syria, Jordan, Lebanon, and Israel/Palestine) and Iraq. Like the Turkish officers to the north, these Arab officers also continued the struggle of World War One, trying to wrest control of their land from the occupying armies of Britain and France. They rejected the new borders imposed on the Middle East in the post-war settlement, and they battled against British and French troops by moving from place to place as if the borders did not exist: in Iraq in 1920, in Syria from 1920-1927, and in Palestine in 1936 and 1948. Their aim was to establish a unified, independent Arab state in the Arab provinces of the former Ottoman Empire.

Seeking help in the fight against the British and French, these Arab officers appealed to their former Turkish comrades, who by then were serving as officers in the newly created Turkish Army. But the Turks were exhausted by their own struggle to wrest parts of Anatolia from British and French control, and they turned inwards, focusing now on building their new republic and defending its borders.

Left on their own, without the military infrastructure of the once mighty Ottoman army, the Arab fighters struggled but ultimately failed to expel colonial troops from Arab lands. If they had succeeded in their efforts, the Middle East would look very different today.

Fawzi al-Qawuqji was one former Ottoman Arab officer who devoted his life to fighting against colonial occupation.

His life story reflects the larger story of Arab resistance against colonialism between 1918 and 1948. He was born in 1894 in Tripoli, then under the rule of the Ottoman Empire, and he enrolled as a cadet in the Military College in Istanbul. He fought as a young officer on the Ottoman side during the First World War, and never joined the Arab revolt in the Hijaz.

When the Ottoman Empire collapsed in 1918, al-Qawuqji faced an uncertain future. He could go north and fight with Mustafa Kemal’s forces in Anatolia, or he could join the Arab army established by King Faysal in Syria in 1920. He chose to join Faysal’s army and to fight for an independent Arab state in Syria.

When the French defeated King Faysal’s forces at the Battle of Maysalun in July 1920, Faysal was expelled from Syria by its new European occupiers, and al-Qawuqji was once again left without a professional future.

As French rule over Syria deepened and solidified, al-Qawuqji decided to join the French army, eventually serving as an officer in a garrison in Hama.

But serving in the army of Syria’s foreign occupiers weighed heavily on him. In the autumn of 1925, in the middle of the Great Syrian revolt, al-Qawuqji mutinied against his French commanding officer and led an uprising against the French in Hama.

One of his fellow rebels and close confidantes explained al-Qawuqji’s choice to leave his comfortable life as an officer in the French army and join the Syrian rebels: al-Qawuqji “wanted freedom from the life he was living by replacing it with a life of honour and dignity”.

For al-Qawuqji there was no turning back. The French government condemned him as a traitor and deserter, and put out a warrant for his arrest. From that moment on, al-Qawuqji lived the life of a rebel soldier.

After the collapse of the Great Syrian revolt, al-Qawuqji went into exile. He spent several years in the Hijaz working for Ibn Saud and helping to train the new Saudi army.

When al-Qawuqji left the Hijaz – following a dispute with Prince Faysal, one of Ibn Saud’s sons – he moved to Baghdad. From Baghdad, al-Qawuqji organised a small company of irregular soldiers and in the late summer of 1936, he led them into Palestine, where they joined the Palestinian revolt against the British.

Al-Qawuqji’s role in the Palestinian revolt made him famous throughout Palestine. He was celebrated in poems and songs, including one by the Palestinian poet Fadwa Tuqan, who described him as a “hero of heroes” and “the flower of all young men”. Palestinian fighters hung framed photographs of him on their walls, and postcards depicting his exploits were handed out at religious festivals. When al-Qawuqji left Palestine and returned to Baghdad, the pro-British Iraqi government sent him into exile in Kirkuk as a way of keeping him from making trouble. A pro-German revolt against the pro-British Iraqi government broke out in 1941, and al-Qawuqji joined the Iraqi fighters. He carried on leading a small band of loyal troops long after the Iraqi rebel leadership had been defeated by the British. German officers and diplomats stationed in what was then Vichy-controlled Syria supported al-Qawuqji in his continued attempts to attack British army installations and disrupt the flow of the oil that was so crucial to the Allied war effort.

In the summer of 1941, al-Qawuqji was severely wounded when two British airplanes attacked him and his men as they travelled in the desert near Palmyra. His German contacts arranged for him to be flown to Berlin, where he underwent extensive surgery.

During the surgery 19 bullets and pieces of car metal were removed from his body. But the surgeon left one bullet still lodged in his head, afraid that attempting to remove it would cause brain damage. Al-Qawuqji suffered from headaches for the rest of his life as a result.

Al-Qawuqji remained in Germany throughout World War Two. He was one of many Arab nationalists who believed that a German victory in the Middle East would finally bring independence from British and French colonial rule. Other anti-colonial activists – such as the Indian nationalist Subhas Chandra Bose and the Irish nationalist Sean Russell – also spent the war years in Berlin lobbying the Germans to support their fight for independence.

Al-Qawuqji’s time in Berlin was marred by his growing rivalry with Hajj Amin Al Husayni, the de-facto leader of the Palestinians and also an Arab exile in Berlin. Hajj Amin did everything he could to undermine al-Qawuqji’s credibility with his German interlocutors, including accusing him of being a British spy.

When the Russians occupied Berlin in the summer of 1945, al-Qawuqji found himself in a Russian prison camp. It was not until 1947 that he managed to escape from the Russians, finding his way eventually to Paris, where he was welcomed by the Lebanese Legation in Paris as a long-lost hero.

Al-Qawuqji returned to the Middle East in March 1947. A lot had changed since his dramatic departure in 1941. Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan had all gained independence. The Jewish community in Palestine had increased in number to about 600,000 souls, many of them refugees from Nazi-occupied lands.

It became clear that the British, who had ruled Palestine since 1917, were preparing to pack up and go home. A war between the Palestinian Arabs and the Jewish community in Palestine was on the horizon. The Arab League, created just two years previously, started to plan for it. As part of these preparations, the League established a volunteer army that drew its troops from all across the Arab lands.

In late December 1947, the Arab League appointed al-Qawuqji as field commander of this army, which became known as the Arab Liberation Army (Jaysh Al Inqadh). By January 1948, the British had formally declared their intention to leave Palestine and were already starting to withdraw their troops. Al-Qawuqji had only a few weeks to find officers, to recruit and train ordinary ranks, and to procure supplies, weapons and ammunition.

For al-Qawuqji, fighting against the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine was just another war against European colonial control of Arab lands. But in contrast to 1936, when he led a small irregular band of rebels into Palestine, al-Qawuqji now found himself commanding a modern army of about 4,000 men. The Arab Liberation Army entered Palestine in January 1948 and engaged Jewish forces in several battles over the following months.

Most ALA officers and soldiers fought bravely, but al-Qawuqji was plagued by logistical and command-and-control problems throughout the war. He never had a large enough number of experienced officers at his command. Wireless communications constantly broke down, and even when he did manage to get through to his own superiors in Damascus, the League responded slowly and haphazardly to his requests for the supplies and ammunition that he and his troops so desperately needed.

The war ended well for the Jewish community: a resounding military victory and the establishment of the state of Israel over a far greater proportion of Palestine than the Yishuv had been promised in the UN’s Partition Resolution of December 1947. Seven hundred and fifty thousand Palestinians were expelled or fled from their towns and villages, creating the Palestinian refugee crisis that is still ongoing today, and Palestine was erased from the map.

Al-Qawuqji retired from public life after the war. He left a complex legacy. Some still think of him as a great hero of the post-World War One struggle for Arab independence. For others, he is irredeemably implicated in the Arab defeat in 1948.

Many regard him and his generation as representatives of an era of hopeless and costly military adventures, stretching from 1948 to today.

Because of the stain of 1948, there is very little written – either in English or Arabic – about al-Qawuqji and his fellow ex-Ottoman officers. But these men fought hard against the colonial occupation of Arab lands from 1918-1948. They never accepted colonial borders and struggled instead for a different vision of the future.

Their story deserves be told.

Laila Parsons teaches modern Middle East history at McGill University and is the author of The Commander: Fawzi al-Qawuqji and Fight for Arab Liberation, 1914-1948