In 1957, the Christian Maronite president of Lebanon, Camille Chamoun, unveiled a statue of a Muslim figure whose life spanned several eras and whose politics helped shape the nation. The sculpture was of Lebanon's first post-independence prime minister, Riad Al Solh, a great political pragmatist who made his name as an uncompromising Arab nationalist. At the time of its unveiling, six years had passed since Al Solh's assassination in Amman. In the intervening period, Al Solh's vision for the country had hit uncertain times – and in 1958, the fledgling Lebanese state would be plunged into months of civil war. Another conflict, which lasted from 1975 until 1990, would almost finish the country for good.

Despite that, Al Solh, who was born 125 years ago today, remains part of Lebanon's national fabric, as does his statue, which today stands proudly in Beirut in the square that bears his name. But as Lebanon grapples with its place in a restive Arab region, the question must be asked: how should history judge the legacy and motivations of a man who made a vibrant, but ultra-sectarian, nation state on the Mediterranean possible?

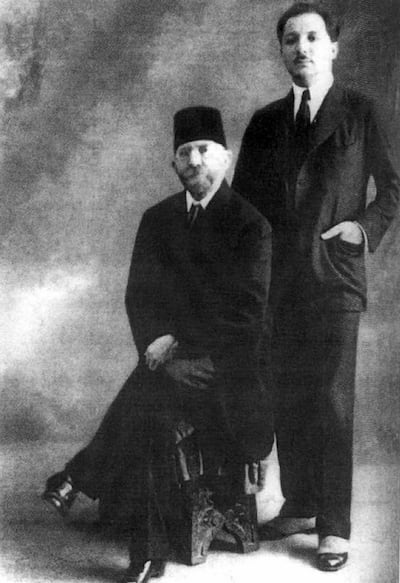

Al Solh grew up surrounded by politics

"Al Solh represents a Sunni politician who, in a post-Ottoman Middle East, manoeuvred from pan-Arabism and initial rejection of a Lebanese state to eventual acceptance of that state, with a central role for Sunnis in it," says Michael Young, author of 2014 book The Ghosts of Martyrs Square: An Eyewitness Account of Lebanon's Life Struggle.

Al Solh was born a citizen of the Ottoman Empire in Sidon on August 17, 1894, and died on July 17, 1951 a fully fledged Lebanese citizen. The years in between were pivotal to the creation of the nation, and Al Solh, after a political about-face, had an important role in making it happen. He grew up surrounded by politics. He spent his formative years living in Istanbul with his family, on account of his father's work in the Ottoman Parliament. At the time, much of the land that would become Lebanon was confined to the autonomous Ottoman province of Mount Lebanon, while Beirut was an Ottoman coastal town.

In October 1918, with the First World War nearing its end, Faisal bin Hussein, son of the Sharif of Makkah and commander of the forces that defeated the Ottomans in the Arab Revolt, swept into Damascus and bestowed a cabinet position on Al Solh's father, Rida, who had severed his Ottoman loyalties.

Through his father, Riad Al Solh found himself at the centre of the fight for Arab independence. But this experience was short-lived, and two years after the revolt, Faisal's dreams of glorious Arab unity were shattered by the Anglo-French Sykes-Picot Agreement, which carved up the Middle East into colonial spheres of influence.

Al Solh became a hunted man, sentenced to death

After the collapse of Faisal's grand plan and the allocation of Lebanon (and Syria) to the French, Riad Al Solh was a hunted man. France sentenced him to death in absentia in August 1920 – a punishment that was later commuted to exile – after he rejected France's creation of Greater Lebanon and its separation from Syria as distinct political entities.

In 1924, Al Solh returned to Greater Lebanon, the French-established mandate within the larger borders of the modern state. He was exiled again for his participation in the unsuccessful Great Syrian Revolt from 1925 until 1927 – when Arab nationalists across Mandatory Lebanon and Syria sought to rid themselves of French rule.

By the 1930s, the great pan-Arabist was beginning to cool his nationalist fervour and embrace the political realities of the mandate. "Even though he was very much an Arab nationalist, he realised the French-drawn borders had made [Lebanon] a fait accompli," says Caroline Attie, author of 2003's Struggle in the Levant: Lebanon in the 1950s. "And he reconciled himself to that."

'On pragmatic grounds, he ended up promoting France’s ‘Grand Liban’

William Harris, author of 2012 book Lebanon: A History, 600 – 2011, says he agrees with that assessment. He argues that "in theory, Al Solh never abandoned the ultimate goal of a big Arab state, but … on pragmatic grounds, he ended up promoting France's 'Grand Liban'".

It is crucial to note that "Riad Al Solh belonged to the first wave of Arab nationalist notables straddling Ottoman and post-Ottoman worlds," says Hicham Safieddine, a lecturer in Modern Arab history at King's College London. "They often held conservative notions of independence that sought a modus vivendi [way of life] with colonial powers without total subjugation. We have to understand Al Solh's Arab nationalism and its transformation … in that context."

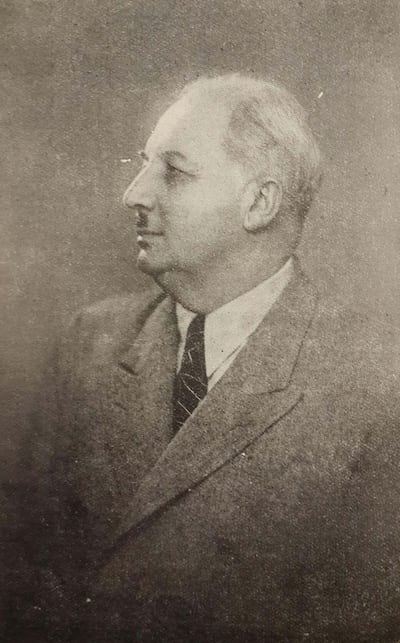

By 1940, Al Solh was the leading figure among Lebanon's Sunnis and, according to Patrick Seale, whose biography of Al Solh – The Struggle for Arab Independence: Riad Al Solh and the Makers of the Modern Middle East – was published in 2010, a man whose "great qualities of charm, wit and shrewdness" marked him out from the crowd.

How Al Solh became prime minister

As the Second World War raged, Lebanon was ostensibly given independence by the French in 1941. But real sovereignty remained elusive and, two years later, Al Solh and Christian Maronite Bishara El Khoury assumed the roles of prime minister and president respectively and jointly agreed the National Pact, which forms the basis of today's Lebanese republic.

This arrangement aligned power along sectarian lines, stipulating that the presidency must go to a Maronite Christian, the role of prime minister to a Sunni Muslim, while the speaker of parliament must be a Shiite Muslim. With confessional politics established in Mount Lebanon in the mid-19th century – and continued under the French mandate – Al Solh was "a pragmatist, who was just working within the system", says Attie.

Safieddine, however, has some misgivings. The author of Banking on the State: The Financial Foundations of Lebanon, published last month, says the volatile confessional nature of modern Lebanon can, to some extent, be laid at Al Solh's door. "He was partly responsible for reproducing sectarianism," he says. "By choosing to support the Lebanese sectarian arrangement despite his Arab nationalist standing, he legitimised sectarianism and gave it a lease of life after the French had set it up."

Al Solh's release from jail is today celebrated as Lebanon’s independence day

The French eventually gave up their colonial claims on Lebanon, but not before putting people such as Al Solh and El Khoury in jail in a final desperate bid to retain power. Their release on November 22, 1943, is today celebrated as Lebanon's independence day.

Al Solh went on to serve as newly independent Lebanon's prime minister twice. But he was killed on a lonely stretch of road in Amman in 1951, when he was gunned down after a meeting with Jordanian officials only months after leaving office. Antoun Saadeh, founder of the Syrian Social Nationalist Party, was executed in 1949 on the orders of the Al Solh administration after a botched coup attempt in Lebanon. SSNP assassins are thought to have killed Al Solh in revenge. With his death, the country's Sunni Muslims lost their greatest advocate.

Al Solh's legacy lives on through his family

Years after his death, however, Al Solh's familial legacy thrives thanks to the prominence of his daughters. They include Leila Al Solh, who made Lebanese history when she and Wafaa Hamze became the first women to hold cabinet positions in 2004. Today, Leila Al Solh is vice president of Lebanese philanthropic body Alwaleed bin Talal Humanitarian Foundation, and is widely regarded as one of the most powerful women in the Middle East.

The National Pact and the continuation of its power-sharing arrangement remains Al Solh's political legacy. His confessional framework has resulted in a functionally volatile Arab republic, but only 15 years after independence, Chamoun upset the delicate balance of the agreement by embracing the American anti-Soviet Eisenhower Doctrine, prompting the brief 1958 civil war.

Attie explains that after Al Solh's time in office, "there was no person of stature to counterbalance the president", demonstrating how easily the National Pact could be violated. The 1989 Taif Agreement, which negotiated an end to the country's 1975-1990 civil war, gave more power to the Lebanese prime minister.

Yet many observers agree that Al Solh's conduct in office is more worthy of praise than that of the country's current leaders. Young says Al Solh now brings a sort of nostalgia for "the kind of politician the Lebanese have come to idealise, or mythologise, from their past, in stark contrast to the lamentable crew in place today".

Abdelmawla Al Solh, a distant relation of the former prime minister and a one-time political adviser to former Lebanese prime minister Takieddin Al Solh during the 1970s, agrees. "He was a true statesman – he and his colleagues built Lebanon," he says. "If he saw the country today, he would be shocked at the corruption. He was clean by comparison."

As his statue stands tall in downtown Beirut, Al Solh will forever be watching his country.