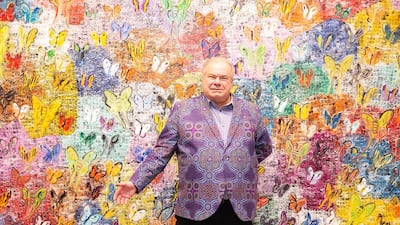

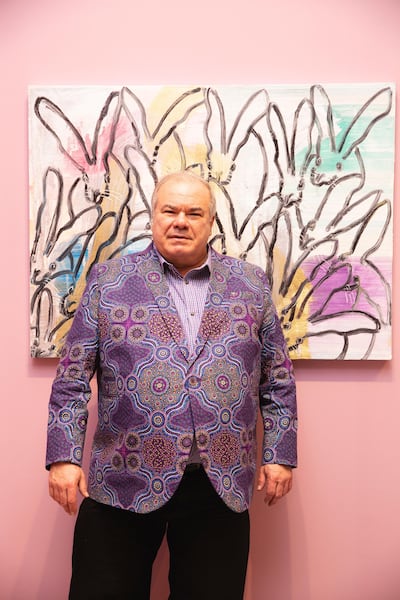

"I have painted hundreds of rabbits but each one is different, each has its own personality, and it just comes through me," explains Hunt Slonem. The American artist is probably best known for his charming paintings of birds, butterflies and rabbits, urgently captured as if the creatures might lope out of sight at any moment, and it is a theme he has been loyal to for many years.

"It's not like I decide I will now paint a rabbit with a smile or a scowl, or ears pointed this way or that, they just flow. It's like a snowstorm, where each snowflake is different; this is a blizzard of bunny-flakes," he says with a laugh.

Like many artists before him, Slonem has made the conscious choice to revisit the same subject again and again, forcing himself to see it afresh each time.

"Repetition is like saying rosary or a prayer," he says. "I used to stay in an ashram in India and we used to take walks and look at nature and recite mantras. If you think about a tree, it is made up of millions of leaves that are all very slightly different, just like flowers or grass.

"So I put two and two together in my head and realised that repetition is a divine message, rather than a stupid lack of intelligence."

Restoring neglected buildings in the US

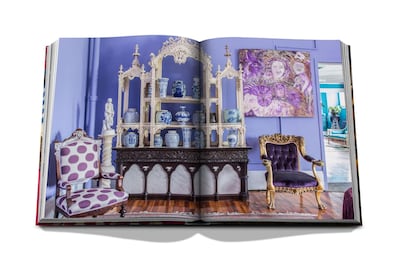

The artist was in the UAE recently to launch his latest book, Gatekeeper: World Of Folly, a visual feast that takes the reader through the recently restored Armoury Building in Pennsylvania, page by lavish page.

Built in the late 1890s, the building was home to the National Guard, and was known as the Colonel Louis Watres Armoury Building. During its life, five US presidents gave speeches in its halls, but it was deemed surplus to requirements recently and decommissioned.

Coincidentally, Slonem was also being ousted from his New York studio due to redevelopment work, and needed somewhere large enough to absorb his collection of furniture and old artwork. At 9,476 square metres, he realised the Armoury was exactly what he was looking for. "I worked on it for four years," Slonem says. "It's a whole city block, and some of the rooms are 4,645 square metres. I was changing studios and I needed a place to put my things."

Each room has now been reinvented, in luscious jewel tones, and filled with brightly coloured, artfully curated objects from Slonem's personal collection. He gathers pieces wherever he travels, setting aside treasures he feels would best complement a space.

"I find [pieces] in auction houses and flea markets. I collect wherever I go," he says. "I took on the Armoury as a project, and I designed everything and placed my collections of antiques and my early works, which have been in storage for 30 years. So it has been quite an asset to review what I have done and see it for the first time in years."

As well as the Armoury, Slonem is restoring other neglected buildings around the US, including the Madewood Plantation House in Louisiana, which is regarded as the finest Greek Revivalist mansion in the South, and the Woolworth Mansion in New York, constructed by tycoon Charles Sumner Woolworth. In each case, Slonem has poured time and money into painstakingly bringing the buildings back to life.

"It is such a thrill saving these old homes and it is part of my art – designing them and the placement of things," he says. "I wake up in the middle of the night and get colour ideas. I do wallpaper and fabrics with a company called Lee Jofa and that has been a wonderful resource for all the furniture we have reupholstered, which is in the thousands of pieces now."

Finding inspiration

Entirely self-funded, Slonem is using the money made through his art to help preserve American heritage. "It's only through my work – it's not a gift from anyone – so it is a nice extension of my art," he says. "Let's see how far I go, we are up to seven houses so far.

"I like the idea of time travel and going through the veil, and there are a lot of metaphysical references in my work, which you can feel in these three-dimensional homes, a combination of all these different elements – the salvations of these lost articles, reclaimed and repurposed, but with my stamp on them, in fabric or colour. I like creative environments. I have recently acquired another plantation and we are full blown into restoring that, bringing it back to a safe place structurally, so it can survive another hundred years."

Aside from a need to be altruistic, Slonem is following a long artistic tradition of creating, and leaving, buildings as large-scale artworks. "I don't consider myself an interior designer by any means, I have never done anything for anyone else, this is just my passion as an artist," he says. "And I think this is one of the most interesting things an artist can leave. Gustave Moreau's house in Paris is fascinating and there have been many books on artists' homes, which have been an inspiration, so I hope to leave a foundation where people can come and visit them.

"I have always been inspired by artists' collections, like Picasso, who had all of these chateaux, and filled them up, locked the door and moved on to the next one. I found that very inspiring as a child and the great studios of the 19th century, where the studios were as much a work of art as what came out of them. And it gets me away from the easel for a few minutes."

The easel in question came out of the New York Neo-expressionist school of the 1970s, alongside the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Norris Embry. While using the same urgency of line to depict an image, unlike his peers, Slonem took a softer, less confrontational tone in his work, making him hesitant at being tied to one moniker.

"I like non-categories," Slonem says. "I prefer [to be called] an installation artist. I also do all kinds of things, I do monumental sculpture – like a [8.5 metre] butterfly sculpture for a butterfly park in Louisiana. So, it is hard to be pigeonholed."

As a self-confessed workaholic, Slonem paints every day and is rumoured to start each day by producing five of his famous "bunny" paintings, dashed off at furious speed. "It's true," he says with a laugh. "Not first thing, but usually every day. I was inspired by Hans Hofmann, the painter, and his warm-up paintings. He used to do little studies every day and I like hanging them in groups of a hundred or so in antique frames, salon style, so the little thing becomes part of a bigger unit."

Following his calling

A keen observer of nature, Slonem has his own aviary, from which he creates his bird paintings from life, leading to the inevitable question: does he also have a room filled with rabbits-turned-artist's muses?

"Metaphysically, not actually. I had them as a child," he says. "I was even given one that was about to be fed to an anaconda. That was my last one. In the new movie about Queen Anne, The Favourite, she had something like 13 rabbits, and I was practically painting them as I watched it, I loved that."

With his artworks now sitting in the permanent collections of The Guggenheim, The Metropolitan Museum of Art and The Whitney Museum of American Art, Slonem could be forgiven for taking some time off. However, there is little sign of him slowing down.

"I have lots of new book projects and hopefully a movie will come into it at some point," he says. "Albert Maysles had started to do a documentary on me before he died. My work has been in movies. We had Beautiful Creatures, with Jeremy Irons, shot at Lakeside Plantation, and Jude Law, Sean Penn and Kate Winslet with All The King's Men in another, and we just had The Beguiled with Nicole Kidman, and Beyonce's music video for Lemonade at my other houses. I love it when the work jumps out into the world in other ways, through books and fabrics and things like that."

Although his schedule is now full, divided between creating books, wallpaper and full-scale restoration work, art remains his only calling. "It was all I ever wanted to do," he says. "My grandfather painted a bit and I was surrounded by artworks growing up, as he used to send them to us.

"My father was in the military so we had models of missiles and submarines on the coffee tables, and then the wonderful fresh wet paint of my grandfather's paintings. So I went for the paintings."

Thankfully for us, it seems he made the right choice.