Baghdad October 23, 1918. After four gruelling, disastrous years the Allies and the Ottoman Empire are still at war in Mesopotamia and the Levant, but only just.

The exhausted Ottoman army is in tatters. A month earlier it suffered more than 25,000 casualties at a single, disastrous battle at Megiddo in Palestine – the site of the Biblical Armageddon – an action that paved the way for the subsequent capture of Baalbek and Damascus.

The ancient city of Homs had fallen to allied forces on October 16 and now, British imperial and French troops under General Sir Edmund Allenby and Arab irregulars led by Colonel T E Lawrence are preparing for the final assault on the ancient city of Aleppo, a trophy whose capture will deliver the Syrian campaign’s coup de grace.

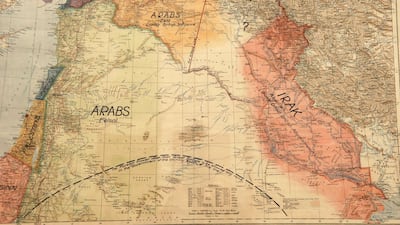

As this military endgame unfolds, time and territory are suddenly more important than ever, especially for the British who, despite earlier agreements with their allies, have their own designs on the region and the future shape of power politics throughout the Middle East. Though nominally still allies, it is now Britain and France, not the Allies and the Ottomans, who are really vying for supremacy throughout the territories that were to become Syria, Jordan, Palestine and Northern Iraq.

Conventional wisdom has it that the next century of Middle East history was set in train by the Sykes-Picot line of 1916 (the secret agreement between the Britain and France to carve up the remnants of the Ottoman Empire between them). But that ignores the vast amount of territory acquired by military force in the following, final two years of the war, which radically redrew the map again. So perhaps it is the armistice of November 11, 2018, that we really should mark as the centenary of the Middle East as we know it today.

“The kind of imperial rivalries that had led to the outbreak of war were back in play even before the war was over” says the historian James Barr. “The British were now manoeuvring for strategic best advantage.”

It is within this context that the 48-year-old commander of the third Indian Corps, lieutenant-general Sir Alexander Stanhope Cobbe VC, DSO, was ordered to leave Baghdad, which the British had occupied since 1917, and to proceed up the River Tigris at all possible speed on what was to become the most controversial operation of his long and distinguished career.

The orders from London were vague, but their infringement of the terms of the now infamous Sykes-Picot Agreement, which had been devised in 1916 as a way of dissipating potential Anglo-French tensions, was not in doubt.

"After dinner on 6 October 1918 David Lloyd George began to mull over how he would go about 'cutting up Turkey'" Barr writes in A Line in the Sand: Britain, France and the struggle that shaped the Middle East.

"This was a continuation of Anglo-French rivalry in the region that can be dated back to the moment Napoleon invaded Egypt," Barr tells me. "The Sykes-Picot agreement had provided a blueprint for the post-war settlement, but it was not one that Lloyd George liked."

As far as the British prime minister was concerned, the post-war settlement would now be decided by the facts on the ground and not by the line that Sir Mark Sykes and Francois Georges-Picot had famously drawn between the ‘E’ in Acre and the last ‘K’ in Kirkuk.

Although the British and the French had already discussed the potential terms of a forthcoming armistice with the Ottomans, nobody knew exactly when this might be concluded, so Cobbe was given until that moment to secure the removal or surrender of Ottoman troops in an area that had already promised to the French. The aim, Barr explains using the words of one of the combatants, “was to score as ‘many times as possible, before the final whistle blows’.”

A sizeable Anglo-Indian force of cavalry and infantry supported by artillery and armoured cars, Cobbe’s column left Baghdad and marched without rest to cover a remarkable 120 kilometres (75 miles) in just 39 hours before engaging in what was to become the final action in the war in Mesopotamia, the Battle of Sharqat. If Cobbe’s orders were vague there was no doubt about the strategic value of his ultimate goal, Mosul, a prize that had become something of an obsession not just for his immediate commander, lieutenant-general William Marshall, but for London as well.

For Marshall, commander-in-chief of British forces in Mesopotamia, Mosul's importance was tactical as well as strategic, as Dr Rod Thornton, a senior lecturer in the Defence Studies Department of King's College London has explained in Why Islamic State is wrong: Sykes-Picot is not responsible for controversial borders in the Middle East - the British Army is.

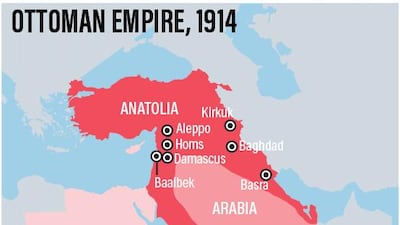

The city of Mosul and its surrounding administrative region, or vilayet, operated as the breadbasket of the larger economic region, which also contained the vilayets of Baghdad and Basra, known to the Ottomans as Al Iraq. Without Mosul under British control the less fertile Baghdad and Basra faced the very real possibility of starvation and shortages that would surely result in future civil unrest.

Similarly, if Mosul remained under Ottoman control its minority Christian population, who were largely responsible for farming the vilayet, might flood south in fear of reprisals, creating a potentially destabilising refugee crisis.

As Barr explains in A Line in the Sand, London viewed Mosul through a global rather than regional lens and its concerns were quite different.

_____________________________

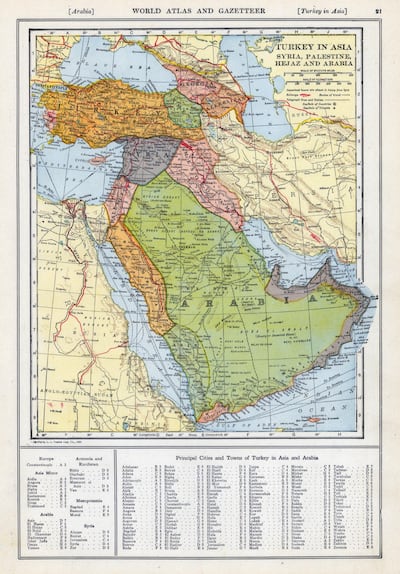

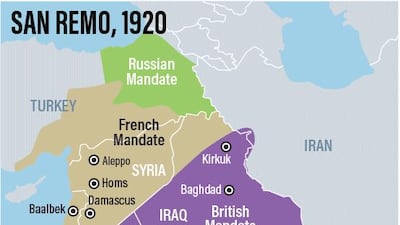

In 1914, as war broke out, the Ottoman Empire consisted of core territory and outlying areas under “nominal” control. Sykes-Picot redrew the map in 1916 into areas of British, French and Russian rule and “buffer” zones under British and French protection. The San Remo meeting of Allied Powers in 1920 changed those boundaries again, producing the colonial compromise of the mandate system.

_____________________________

Earlier that summer a senior admiral in the Royal Navy had produced a memorandum on the role that oil would play as the marine fuel of the future and of the strategic importance of securing oil reserves of the type that were believed to be found in the region north of Mosul and Kirkuk.

The memorandum was brought to Lloyd George’s attention by his cabinet secretary, Maurice Hankey, a former intelligence officer who highlighted the role that access to oil would play in maintaining Britain’s naval supremacy, not least in the face of increased hostility and competition from Britain’s future strategic rival, the United States.

The Battle of Sharqat concluded on the same day, October 30, that British and Ottoman negotiators agreed the terms of the Armistice of Mudros, ending hostilities throughout the Middle East, but unfortunately for the British, Cobbe was still 12 miles short of Mosul when the armistice was declared at 12pm on October 31.

Ignoring the terms of both the armistice and the Sykes-Picot agreement, the British pushed on in the face of vehement Ottoman protests, not just to Mosul, which they entered on November 1, but to take control of the whole wheat- and oil-rich vilayet, which was secured by November 14.

The First World War in the Middle East, a conflict that has been described as the most catastrophic event to befall the region since the Mongol invasions of the 13th century and the arrival of the Black Death, had finally come to an end, two weeks late and three days after the armistice on the Western Front.

For the University of Oxford’s Professor Eugene Rogan, the Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 and the end of the war in 1918 may be hugely symbolic moments for the people of the region, but historically they have to be understood as part of a broader series of events that resulted in its fateful partition.

For the historian, 1918 remains an important milestone because the Armistice represents the end of the First World War in the Middle East and the moment when the Arab world fell out of the control of the Ottoman empire and came under the control of the victorious European powers.

"But it wasn't until the 1920s that the terms of the peace had been drafted and where the final disposition of Ottoman lands was agreed by the victorious powers," says the author of The Fall of the Ottomans: the Great War in the Middle East 1914-1920.

Rogan is keen to point out that other, now largely forgotten events, were just as important in determining the region’s future, such as the 1915 Constantinople Agreement between Czarist Russia, France and Great Britain, agreed on the eve of the Gallipoli campaign, which kickstarted European plans for the Ottoman Empire’s dismemberment and the meeting of the Allied Powers at San Remo in 1920.

“That’s where they actually iron out boundaries that more or less look like the map of the Middle East as it looks today,” Rogan insists. “It’s San Remo that really gives us the map of the Middle East, not Sykes-Picot.”

For Rogan, however, what makes the First World War such an important turning point is because, for more than any other part of the world, the Middle East still lives with the legacy of that post-war settlement and the partition that was imposed upon it, a settlement that saw the region as little more than Asian territory to be managed by European empires.

“They never consulted with the people of the region to gain their consent to the national solutions that were imposed and this left very enduring boundaries, but it also left very enduring conflicts that were a product of the way the boundaries were drawn.”

A litany of double-dealing, cynical manipulation, broken promises and often ruthless violence, those wartime decisions contributed directly to the diplomatic crises that continue to define the region to this day.

If the fateful Balfour Declaration of 1917 contributed to the ongoing tragedy of the Arab-Israeli crisis, then in Rogan’s estimation the French attempt to create a Christian nation state in Lebanon not only contributed to the country’s intractable internal sectarian divisions but to conflict with Syria, which has never been reconciled to its borders or its division.

Similar issues have arisen several times as a result of the boundary that was drawn between Iraq and Kuwait while the Kurds, whose national aspirations were ignored completely, have been engaged in struggles with each of their host nations – Turkey, Iran and Iraq – in their own thwarted quest for self-determination.

Rogan’s assessment chimes with the conclusions drawn by the Jordanian historian Dr Mahjoob Zweiri, associate professor in Contemporary History and Politics of the Middle East and the Head of Humanities Department at Qatar University.

“The whole debate about sectarianism, the whole debate about Arab Nationalism, the whole debate about the role of the state, the whole debate about corruption, about the elite, all of those elements the Arabs and others are now engaged in were rooted then,” Dr Zweiri said at the time of the war’s previous centenary, in 2014.

“I think, in addition to all that, the finger prints of outsiders – at that time Britain and France – in 2014-15 the Americans, it’s the same but with different players, the same scenarios, the same ideas, the same slogans, the same debates.”

_________________

Read more:

The forgotten Muslim heroes of WWI

Sykes-Picot is history ... it should stay that way

A century of fatal and conspiratorial games

Book review: The Vanquished exposes the bloody aftershocks of the First World War

_________________

For Rogan, the tragedy of the region’s history is the all too tangible way that it refuses to recede, whereas in Europe and North America these are issues that have largely been consigned to the archives, regardless of the current wave of commemoration. “I don’t think the region can put the First Word War behind it or have the same closure that Britain and Europe enjoys as something that is done and dusted,” he laments.

“I think there remain outstanding conflicts that reflect the way that the state system was applied to the region, that will continue to be living legacies for some time to come.”