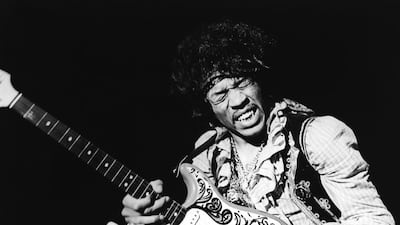

There's a scene in Jimi: All Is By My Side, a new feature film about the electrified life of Jimi Hendrix, in which the young, still-developing guitarist tears off on a solo and the sound, slowly and ever so mesmerisingly, fades away. There he is: one of rock music's most enduring legends, maybe the greatest guitarist of all time, and as all the noise and clamour quiets down, he stands as just a lone guy writhing on stage and wiggling his fingers around. Lots of people did it before him and many more have done it since, so what made his wiggling – the same as most, with just a few fingers, some strings and a long, expectant fret board – so different and distinct?

The movie does little to help answer the question. As played by André Benjamin, better-known as André 3000 from the hip-hop group Outkast, the Hendrix of the film is a bit of a cipher, a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. His motivations are less than clear, and his behaviour, all of it during the early years of his career, is perplexing when it makes any sense at all.

None of that is a condition for an unsatisfying film, of course, but in the case of this one, the fates are unkind. Though the pedigree is strong – it was written and directed by John Ridley, who wrote the screenplay for the celebrated 12 Years a Slave – the film proves most effective at somehow presenting Jimi Hendrix, of all people, as a dithering, directionless bore. If not for the hard and ardent work of two Englishwomen who took a liking to him – the first was a curious girlfriend of Rolling Stone Keith Richards (Linda Keith, played by Imogen Poots) and the second a Swinging London hipster on the make (Kathy Etchingham, played by Hayley Atwell) – Hendrix might well have been nothing. He had no real vision, the movie seems to suggest, and even if he did, he probably would have squandered it on his own.

Benjamin is transcendent in his starring role (with his quietness and sensitivity, he alone makes the film worth seeing, and not just solely for Outkast fans), but the rest of it is a missed opportunity to tell a story much more fascinating and multivalent than the movie implies. Better instead to turn to Jimi Hendrix – Hear My Train A Comin' [official website], a documentary produced for the American Masters series on public television and offered up on DVD for the onset of Hendrix-mania expected to surround the fictional film. (Jimi: All Is By My Side comes out in American cinemas on September 26.)

The documentary tells the whole wondrous tale, from Hendrix's start as a guitar-slinging sideman in workaday R&B bands and his early gigs in New York to his name-making stay in London and his journey back to the American homeland to fashion himself as both momentous and huge. Nobody played quite like him, but it took a while, in the years before rock got expressly psychedelic and weird, for his wild style to catch on. Though he found insider fans in London – including The Beatles, whose song Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band he famously covered at a concert just three days after its release, with two Beatles in the audience – Hendrix's major breakout happened at a notorious showing at the Monterey Pop Festival in California. There, he summoned the demons of feedback and noise, showering the crowd in unheard aural emissions and ending it all by getting on his knees and literally setting his guitar on fire.

“People take it for granted now because they’ve seen it,” says the musician Dweezil Zappa in the documentary. “But before that day, there was nothing like that that ever happened in the world.”

After that incendiary appearance, concert promoters started chasing Hendrix down, and he even went on tour with the smiley TV pop band The Monkees. “It’s a huge audience – The Monkees are super-popular,” says an industry voice in the film. “But the reality is that audience is not predisposed to liking anything as jarring and as groundbreaking as that.”

So Hendrix was out on his own, exploring notions of sound that in a very practical way had not existed before his conception of them. His sounds were gnarled, raw, woolly, untamed – zigs and zags of pure unmediated electricity sawing through the ether.

"He connected with people," says the Rolling Stone magazine writer David Fricke. "He connected in his faith that the guitar could take you some place you've never been before. And he made you believe it."

As drama more than documentary, All Is By My Side casts Hendrix as a lone wolf, but Hear My Train A Comin' presents him as a character much more rounded and robust. "I don't think he was really bitten by the serpent of fame," says musician Paul Caruso. "His ego was the right size."

Chas Chandler, who played bass in The Animals before moving to the business side to manage Hendrix early on, adds: “People always made out Jimi to be some sort of tragic character; sort of gloomy, mystical and all the rest of it. He was anything but that. If I think of Jimi, I think of him with a smile on his face.”

It's hard to imagine his demeanour as smile-free when considering another rich new Hendrix release: Miami Pop Festival [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk], a live recording from a concert in 1968. Never officially released before a recent archival offering on CD and vinyl, the set starts off with some routine tuning and instrument checks before a charged zing of feedback clears the air by confusing it. Indeed, it's easy to imagine the very molecules in the atmosphere pausing for an instant to stop and wonder what exactly is going on in a sound so monstrous and strong.

From there, Hendrix launches into Hey Joe, first as a pounding, plodding dirge and, as it carries on, a heavy monumental structure that somehow manages to elude gravity. Hendrix's solos are extraordinary, especially considering their positioning in just the first few minutes of a long set, and the band behind him – Noel Redding on bass and Mitch Mitchell on drums – is savage in its attack.

The sound diverges throughout the set, with guitar theatrics that range from molten drippings in Tax Free to desperate howls of pleasure or pain (or both) in Purple Haze. It's remarkable, and really only part of a story that expanded greatly by just the next year. A pair of new Hendrix reissues – The Cry of Love [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk] and Rainbow Bridge [Amazon.com; Amazon.co.uk]– feature material written for what was to be an ambitious double-album titled First Rays of the New Rising Sun. That album never happened, however, due to Hendrix's early death in 1970, at the age of 27. (The cause was thought to be an accident with sleeping pills.)

But recordings remain and they were doled out on posthumous releases that expanded Hendrix's legacy even further. Rainbow Bridge, available now for the first time on CD (it's coming out as a vinyl reissue, too), is stretchy and discursive, with spots of soul that sound like Sly and the Family Stone and long, groovy blues runs that, dizzyingly, unspool at the same time as they wind tighter and tighter. Hendrix's formidable studio craft is on full aural display, with multi-track effects that he pioneered at hideouts including his state-of-the-art Electric Lady Studios in New York.

You can hear it in a delirious rendition of Star-Spangled Banner, also known across the world as the American national anthem. As it waves here (in a version actually recorded at a different studio, Record Plant), the song is an otherworldly blast, full of high-pitched guitar squeals layered together in a clean, gleaming form much different from the startling version he famously played live at Woodstock.

In the Hear My Train A Comin' documentary, Hendrix himself says: "We don't play it to take away all this greatness that America is supposed to have, but we play it the way the air is in America today. The air is slightly static."

It feels true now even still, decades down the line, with Hendrix’s influence widely felt but still not yet fully assimilated. That he managed to take that static state and turn it into static electricity seems fated to forever fall somewhere beyond the bounds of comprehension – and, with time, all the more intriguingly so.

Andy Battaglia is a New York-based writer whose work appears in The Wall Street Journal, The Wire, Spin and more.