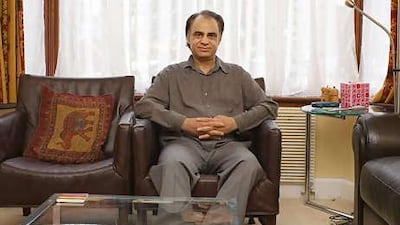

As Ramadan approaches, M talks to the writer and broadcaster Ziauddin Sardar about the five books he feels most accurately reflect the future of Islam. A British Muslim of Pakistani origin, Sardar has written more than 45 books, including his widely acclaimed autobiographies, Desperately Seeking Paradise and Balti Britain. He is the editor of Futures, a monthly journal of policy, planning and futures studies.

It should not come as a surprise to discover that the first book on the future of Islam was written by an Englishman: Wilfrid Scawen Blunt. As a supporter of Arabs, Blunt was aggressively anti-Ottoman and thought the Ottoman Empire was an impediment to the emergence of "progressive thought in Islam". Considering the period in which the essays were written, The Future Of Islam is a very perceptive book, with a genuine, futuristic understanding of the political and intellectual trends of the time.

Blunt made many predictions and quite a few turned out to be true. He predicted the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the transfer of Islam's "metropolis" from Constantinople to Mecca, the emergence of independent Muslim states, and a movement of liberal Islam in Egypt, even the arrival of "a Mahdi" in the Sudan. I think Blunt was spot on when he argued that the future survival of Islam depends on an internal reform of law and ethics. But he was sensible enough to suggest that such reforms are best undertaken by Muslims themselves.The Future Of Islam has its biases and prejudices, but it is worth reading, even almost 130 years after its publication, for Blunt's perceptive insight into Muslim politics and his awareness of the general direction Islam has been moving during the past century.

Most people think that this book is a religious text focused on theological issues. But in my opinion, Muhammad Iqbal (1877-1938), who is renowned in the Indian subcontinent as a poet and philosopher, was the first Muslim futurist. This is a powerful and challenging book, packed with deep insights. Like me, Iqbal was concerned with shaping rather than predicting the future. He was totally disillusioned by religious scholars whom he described as "ignorant" and "absolutely incapable of receiving any fresh inspiration from modern thought and experience". He wanted to develop a modern epistemology of Islam as the basis for the reconstruction of a future Muslim civilisation. He saw the future as an open possibility, not closed and predetermined, and life as an organic unity where everything was connected to everything else. He wanted to change everything, particularly Sharia law, which he saw as arcane and outdated. He argued that every generation has to rethink Islamic law. I think the full impact of Iqbal's futuristic thinking has yet to be appreciated by contemporary Muslims.

Iqbal was certainly one of those who inspired me to write my book, The Future Of Muslim Civilisation.Given that Islam is perforce a future-oriented world view, why is the future so conspicuously absent from contemporary Muslim thought and discourses? Single-handedly for almost a decade I tried to shape a discourse on Islamic futures. When The Future Of Muslim Civilisation was first published in 1979, most Muslim scholars found it difficult to comprehend. Part of the difficulty was due to the fact that there was no internal language for discussing the future of Islam; I had to invent my own language. But there was another problem: the inertia associated with thinking about the future.

This book looks at the future of Islamic fundamentalism in Egypt, Algeria and Saudi Arabia and concludes that it has no future. Faksh offers a refreshing and powerful analysis of the vacuous nature of Islamic fundamentalism; he is very far-sighted but his book is largely neglected. He argues that the threat of Islamic fundamentalism is overstated, and the deep cultural and moral principles of Islam, and its overarching emphasis on diversity and pluralism, will eventually sweep it aside.

Futures of Islam, like futures of most cultures, is open to numerous pluralistic and democratic possibilities. The emphasis of my own work has been on shaping pluralistic and sustainable futures for Muslim societies. But I have to admit that Muslims, as a whole, are not very good at looking towards the future or exploring alternative future paths. We tend to be nostalgic about the glories of our history and fatalistic about our problems.

I think the future of all three monotheistic faiths is intertwined and interconnected. This point is strongly made by Hans Kung in Islam: Past, Present and Future. Kung is undoubtedly the most enlightened Catholic philosopher of our time. Islam is a monumental work: it covers the evolution and development of Islam, the present crisis of Muslim civilisation, and looks at what Kung calls "possibilities for the future". Islam is the last in a trilogy which covered Judaism and Christianity. And Kung is simply brilliant in making connections between the three faiths and highlighting the areas of convergence.

He thinks that Islamic law should and will change in the future to meet the challenge of human rights, gender equality, and the rights of minorities by developing a new ethical framework of rights and responsibilities. He predicts that Muslim politics will acquire "secularity" without totally embracing secularism, and that Islamic economics, including the banking system, will evolve further as a major system of commerce based on ethical principles.

What I really like about the book is Kung's passionate belief that the differences between Islam and the West are more apparent than real and that the religious divide between Islam and the other two Abrahamic faiths can be readily bridged. The deadly threats that humanity faces, he argues, require us to demolish the walls of prejudice, stone by stone. He would argue that it is a necessary requirement for our future survival.

The most urgent task facing Muslim society, I think, is the reformulation of the Sharia. Here, the human rights lawyer, Abdullahi Ahmed An-Naim, has provided an invaluable lead. He argues that Islam cannot have a viable future without rethinking Islamic law and the relationship between religion and the secular state in all Muslim societies. The Sharia needs to be free from state control, he suggests, just as the state should not be allowed to misuse religious authority. I couldn't agree more with his assertion that the idea of human rights and citizenship is totally consistent with Islamic values and norms.

I am always hopeful about the future. After all, a major function of faith is to give us cautious hope. This is why Kung also concludes his book by expressing "unshakeable hope" about the future. But hope is intrinsic in the very idea of future. An awareness of the future can empower people and open up possibilities where none existed before. The future is a frontier where all things are possible, including the possibility of breaking the power and the hold of the present over our future. But for that to happen we should see the future not as a commodity but as a domain of alternative potentials and promises.

This interview first appeared on www.thebrowser.com