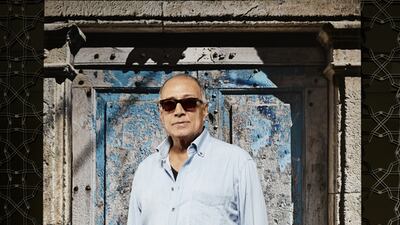

Taken over the past two decades, the photographs of Abbas Kiarostami have remained private – until now. Fifty of the prominent Iranian filmmaker's works, all featuring different doors and curated from his collection of more than 200 images, are on display at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto. Kiarostami, 75, talks to The National about his preoccupation with still life, the loss of historical heritage and the textures of venerable objects.

What took you to photography and to the still image?

I owe it to the 1979 revolution, because it was very hard to make films. I had to go on producing images, so I started taking still pictures. It became a parallel activity afterwards to filmmaking. They interact. There’s a mutual influence.

You are exhibiting still images today when much of the contemporary art world consists of moving images. Is this a coincidence?

If an image is worth seeing, it takes concentration. And contemplation. The reason why there is so much movement is probably that nothing is worth being seen in what is actually shown. This is my way of protesting against that. Look at how people relate to the pictures shown here. They choose the best position, and they stand still in front of it, and they stare at it. This is the kind of opportunity that is given less and less in contemporary art.

Why did you take pictures of doors?

I started with walls, and then walls took me to windows, and windows to doors, but I also have trees and snow. I have eleven collections of motifs. In doors, and also in walls, it’s life, ageing – these are the features that I’ve been attracted to.

These doors have a stately presence. Did they need to be dressed before you photographed them?

If you consider cleansing to be part of that, I must confess that I had to clean them to take off the dust of years. But that was all of it. (Pointing to one photograph) I went in the morning, I washed this, then went for lunch, then I came back after it dried, and was able to take the picture. At the very place where I encountered this door 20 years ago, there is now a grey tower in Tehran.

If you have 200 of these photographs of doors, there are enough for a sequel to this exhibition.

Potentially, yes. But one (exhibition) should be enough. As time went by, the quality of the doors got less interesting, but my camera was getting better. So I had this balance to find between good quality pictures and doors that were worth seeing. I am absolutely sure that none of the doors that you see here are in service. In Italy, where I went scouting locations for my film, Certified Copy, I could not find any of the doors I had seen before.

What does this tell us about our respect for history and our appreciation of objects?

Each of them is a precise image of the person who lived behind it, just as Facebook accounts tend to be now for people. All the subtleties and the details of each door give a very precise idea of the aesthetic approach of the person living there, whereas now they’re replaced by functional doors, opened by a buzzer or code. This is it (points to a door handle in one of the photographs). In Persian, we would call this the lady’s handle. Men would use a rougher one, and women would use the more delicate carved one. It was a way to say who you were, to announce the person behind the door. None of these details exist anymore.

• Abbas Kiarostami: Doors Without Keys is at the Aga Khan Museum in Toronto until March 28. Visit www.agakhanmuseum.org

artslife@thenational.ae