On October 4, 1957, a converted ballistic missile was launched from a secret test range 200 kilometres east of the Aral Sea in what was then the Soviet Socialist Republic of Kazakhstan.

The launch took place at 22:28:34 Moscow Standard Time but the engineers who witnessed the event watched the craft, nervously, for a further 98 minutes – the time it took for the rocket’s payload to complete its elliptical orbit around the Earth – before finally informing their political masters of the news.

The team, led by the 50-year-old aeronautical engineer Sergei Pavlovich Korolev, had succeeded in sending a highly-polished metal sphere the size of a beach ball into a near-Earth orbit.

They referred to the device as Elementary Satellite-1 but we now know it as the Sputnik and as the satellite sped through the heavens its simple onboard radio transmitter emitted a signal, described by the Associated Press as the “deep beep-beep”, that even amateur shortwave radio enthusiasts could hear.

Broadcasting on the night of the launch, an NBC radio journalist captured the resonance of the Sputnik’s signal with a simple instruction: “Listen now for the sound that forevermore separates the old from the new.”

Thanks to a combination of ideological antagonism, personal ambition and nationalism, a new chapter in the history of human ingenuity – the Space Age – had finally begun; the Soviet Union had claimed first honours in the race for the heavens; and the Sputnik Crisis, an unprecedented wave of international political tension and paranoia, was unleashed upon the world.

As the historian Daniel J Boorstin later explained in his Pulitzer Prize-winning book The Americans: The Democratic Experience: "Never before had so small and so harmless an object created such consternation."

For the majority of people who will visit Invisible Threads: Technology and its Discontents, the new show at the Art Gallery at New York University Abu Dhabi which opens this Thursday, the Cold War will be little more than a matter of historical record; but among those who can remember the threat of mutually assured destruction, the show's opening sculpture is likely to produce a profound and visceral response.

An exact replica of an object that no longer exists, Michael Joaquin Grey's sculpture My Sputnik (1990) not only symbolises the dawn of our current Information Age but also epitomises Invisible Threads' stance on the link between art and science, encapsulating as it does the paranoia-inducing dualities of utopianism and determinism, privacy and surveillance, emancipation and control.

“Launching Sputnik was a great technological feat that created a lot of excitement for one part of the globe and lot of anxiety for the other,” explains Bana Kattan, the show’s co-curator who is also assistant curator at the Art Gallery at NYUAD.

“And that’s really what this exhibition is about, the anxiety that we feel when we interact with technology,”

“There’s also a promise that somehow this technology will enrich our lives or expand our capacity as humans. But we’re still trying to figure out how to relate to one another through digital technologies, and we often forget to ask ‘at what cost?’” says Kattan’s co-curator and colleague, Scott Fitzgerald, a media artist who also leads NYUAD’s Interactive Media programme.

Taking its title from a quote by Friedrich Nietzsche, “invisible threads are the strongest ties”, Kattan and Fitzgerald have assembled works by 15 international artists that investigate the invisible networks and structures we do not understand and cannot see but upon which contemporary communication technologies, and life as we know it, now relies.

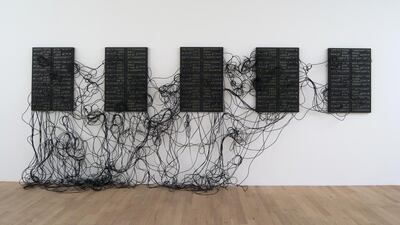

Addie Wagenknecht's XXXX.XXX (2014) consists of a series of five large custom-printed circuit board panels and monitors the network traffic passing through the NYUAD computer network, turning invisible messages into a series of flashing and blinking lights. The point, Fitzgerald explains, is to reveal the layers of abstraction that we now accept, unquestioningly, whenever we use our mobile telephones and computers, send messages via Wi-Fi or consult the internet.

“I know a little bit more than most people about what goes on inside this machine when I send an email, but the reality is that in a lot of ways I still think of the way that happens as magic,” the academic admits. “But maybe faith isn’t enough. Maybe we should try to figure out what’s going on inside of these tools and these machines.”

Other pieces, such as the giant fingerprint from Evan Roth's Multi-Touch Painting series and Heather Dewey-Hagborg's Stranger Visions (2012) set out to examine the impact of modern technology on our sense of self, and the personal data, much of it physical, that can now be collected from us, with or without our consent.

Roth’s work consists of fingerprints lifted from the touchscreens on digital devices, which record our most personal data with every mundane screen-based task we perform, while Dewey-Hagborg’s digitally-printed portrait masks are made from the very stuff of life.

To make them, Dewey-Hagborg collected genetic material – from human hair, chewing gum and even cigarette butts – that she found on the pavements and subways of New York and then, having extracted information from the samples relating to identity traits such as gender, eye colour, facial structures and ancestry, used facial recognition software and a 3-D printer to generate each sculpture.

Dewey-Hagborg’s aim, in creating portraits that are simultaneously highly personal and anonymous, is to draw attention to just how much can be found out about us from the material we accidentally leave behind, and to raise questions about how our own DNA might be used, potentially against us, in an emerging and increasing culture of biological surveillance.

"This is probably one of the most paranoia-inducing pieces in the show. It raises questions about ownership, not just of our image rights but of our fingerprints and our DNA," says Kattan, who insists that the aim of Invisible Threads is not to accentuate the dystopian potential of contemporary technologies.

“Even though there are parts of the show that point in that direction we definitely don’t want to be too negative or too paranoid,” the curator says. But this is such a global topic, we are geographically so central here [in the UAE] and the population is so connected, we feel that this is a really good place to examine these issues and to talk about them.

“You can unlock your iPhone now with your fingerprint. Well guess what, Apple now have all of our fingerprints and what are they going to do with that information?”

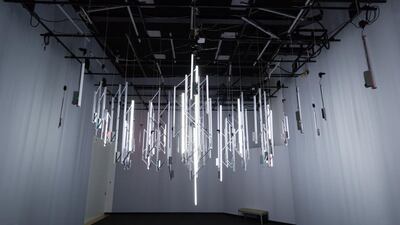

The desire to make the intangible tangible and not to take anything for granted lies at the heart of the show's largest installation, Phillip Stearns's room-sized A Chandelier for One of Many Possible Ends (2014).

Inspired by the Fukushima disaster in March 2011, the largest nuclear catastrophe since Chernobyl in 1986, Stearns’s chandelier is composed of 92 Geiger counters, the same amount as the number of protons in the nucleus of a uranium atom, each of which is connected to a LED light fixture.

The result is a haunting meditation on the processes of life and death, rendered in light, that also provides an audio-visual rendering of the background radioactivity that’s present in the exhibition space.

Each click and flash of a bulb represents the detection of ionising radiation, some of which occurs naturally, but some of which is anthropogenic. A source of contamination great enough to light the entire chandelier would prove fatal, but smaller amounts of ionising radiation contribute to the mutation of DNA, which plays a role in both the formation of cancers and the process of evolution.

Despite its deadly potential, Fitzgerald insists that the chandelier alludes to the use of technology by activists following the Fukushima disaster who refused to accept the Japanese government’s statements about the extent of radioactive contamination.

“They built their own radiation monitors, posted instructions online so that other people could build them and then began to place them throughout the country,” Fitzgerald explains.

“They got an incredibly large number of people to actively engage in an incredibly positive way and they were able to show that things were actually worse than they had been told and so people were able to look after themselves in a responsible fashion.”

Fittingly for a show that starts, chronologically, with its oldest, space-related exhibit, Invisible Threads effectively ends with a brand new work, specially commissioned for the exhibition, that involves an improbable back-to-the-future approach to space exploration.

With his gilded, larger than life-sized Saddam Hussein sculpture Canto III, the Iraqi-born artist Wafaa Bilal created one of the most memorable and improbable images to emerge from both New York's Armory Show and the Venice Biennale in 2015.

The piece is on display in Invisible Threads but it is also accompanied by a smaller version of the sculpture, mounted on a satellite, that will be sent into the upper atmosphere by balloon soon after the NYUAD show has finished. Bilal's idea takes its inspiration from the nascent Iraqi space programme of the 1980s, which got as far as developing its own test satellite, and from a plan, dreamt up by members of the Ba'ath Party, to put a statue of Saddam Hussein into Earth orbit.

That plan was never realised, in part because the Iraqi space programme was hampered by UN sanctions before finally being terminated by the United States invasion of Iraq in 2003, but Bilal aims to make good on the idea and to observe the whole operation using a small camera that he has mounted on the satellite.

As improbable as it sounds, the sculpture embodies the kind of democratisation of technology and access to tools that defines contemporary life.

In the space of a generation, an operation that was previously the province of governments and their military industrial complexes can now be executed by academics and artists, hackers and activists, and as with the invention of the hand axe, of Gutenberg’s printing press or the analysis of an individual’s DNA, that’s a dissemination of technology that represents a cultural revolution in its own right.

• Invisible Threads: Technology and its Discontents is on show at the Art Gallery at NYUAD from September 22 until December 31 (www.nyuad-artgallery.org).

Nick Leech is a feature writer at The National.