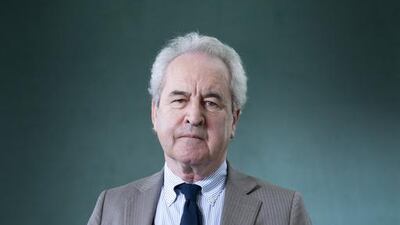

John Banville is a novelist who is magnetised by the past, haunted by memory, consumed by loss, enthralled by bereavement. He is a great chronicler of deprivation; his characters are often experts in the retrospective mode.

In his novel of 2012, Ancient Light, an actor who has recently lost his daughter takes refuge in his memories of the 1950s, and in the beginnings and the ends of first loves. And in his Man Booker winning novel of 2005, The Sea, a recent widower attempts to handle his grief by revisiting a seaside village where he once holidayed as a boy, and where he experienced a childhood trauma.

Both novels are preoccupied with origins: with the point at which a life can start to unravel, with the strange and elusive realm where love begins – and where love begins to go wrong.

Banville's latest work, The Blue Guitar, shares these preoccupations. It tells the story of Oliver Orme, a middle-aged painter who no longer paints, and who is weathering the grief engendered by the loss of his baby daughter, Olivia.

When we encounter him at the opening of the novel, his affair with Polly, the wife of his friend Marcus, has been exposed; and we discover almost immediately that he is a thief: “Call me Autolycus”, he says. “Well, no, don’t. Although I am, like that unfunny clown, a picker-up of unconsidered trifles. Which is a fancy way of saying I steal things.”

Orme does not steal for profit: “The objects, the artefacts, that I purloin – there is a nice word, prim and pursed – are of scant value for the most part. Oftentimes their owners don’t even miss them. This upsets me, puts me in a dither. I won’t say I want to be caught, but I do want the loss to be registered.”

His attitude to theft is quasi-artistic, a means of ordering the world and finding solace, and places him in the tradition of the Nabokovian artiste manqué – one thinks most readily of Humbert Humbert, who also warns us on the opening page of Lolita to beware of his fancy prose style.

And fancy Orme’s prose style is. He speaks in spare, dry, jesting sentences, full of blunt candour and seductive repetitions (“Her tone at times can deliver quite a sting, quite a sting”).

He likes to punctuate his sentences with long and often discordant words (“phantasmagoria”; “borborygmic”; “conflagration”), talk himself into dead-ends, terminate his weak puns with hollow expletives (“Once I was a painter, now I’m a painster. Ha.”), and self-mythologise (“So there you have me. Rome the master painster, who paints no more”).

Banville has always been wiling to court the high style; and readers have always been willing to criticise him for it (how often have you heard the lazy accusation that such-and-such is “just a stylist”?).

Yet what this novel shows is just how integral to Banville’s thematic and structural concerns his use of language can be. Orme speaks with such a tricksy, jaunty, linguistically brilliant voice because he recognises that language has the power to both insulate him from the world and enrapture him with its offer of artistic consolation.

As he says later in the novel: “What concerns me is not things as they are, but as they offer themselves up to being expressed. The expressing is all – and oh, such expressing”; and as he says near its beginning: “Pain compels eloquence – look at me, listen to me.”

As the book progresses (most of it takes place in Orme’s childhood home, where he retreats after the exposure of his affair), Orme tells us more about the pain with which his life is suffused. And as he does so, the high style of the early pages of the book modulates into something calm, open, honest, and often plangent.

The cumulative effect of all of this – the opening ludic exuberance, the subsequent steady softening, the sheer force of Banville’s reflections on grief and loss – is moving, entertaining, edifying and affirmative.

The Blue Guitar is a remarkable achievement: the work of a writer who knows not only about pain and eloquence, but about the consolations of learning how to think, to look and to listen.

Matthew Adams writes for The Times Literary Supplement, The Spectator and The Literary Review. He lives in London.