The infamous Abu Salim prison in Tripoli, nerve centre of Muammar Qaddafi's gulag archipelago, hovers menacingly over Hisham Matar's memoir, The Return. Those who trod its bloodied corridors in the immediate aftermath of the regime's fall in 2011 will not forget the experience.

Of the many images that remain from that day, two in particular persist. First, the extraordinary quantity of medication scattered pell-mell across the hastily liberated blocks. Second, the pitiful sight of chipped out holes in the walls between the cells, allowing the prisoners to communicate with each other and pass on books, medicine and any other possible solace. It was a hollowing, dizzying visit, each cell a macabre installation of despair and survival. For anyone who lost a relative here, it would have been completely eviscerating.

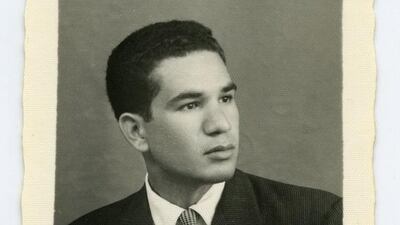

It is no surprise, then, that the prison was not part of Hisham Matar’s return to Libya in 2012, after an exile of 33 years. Ever since his dissident father Jaballa was taken from the family’s apartment in Cairo by Egyptian intelligence in the 1990s and handed over to the Qaddafi regime, Matar, his mother and brother had lived in a suspense of unknowing.

“I worried that if I found myself in those cells I had heard about, imagined, dreamt about for years… that if I found myself in that place where his smell, and times, and spirit lingered (for they must linger), I might be forever undone.”

In the 1990s, the family received a trio of letters from the imprisoned head of the family. “The cruelty of this place far exceeds all of what we have read of the fortress prison of Bastille. The cruelty is in everything but I remain stronger than their tactics of oppression... My forehead does not know how to bow.” And then silence.

The theft of his father, together with uncles and cousins, sends forth torrents of rage which course through him like “a poisoned river”. But there is much more quiet, impotent grief here, accompanied by harrowing meditations on loss and suffering.

The Return is artfully written, the prose deceptively sparse and simple. It seems inappropriate to say a work of this kind is a joy to read yet it manages to be powerfully sustaining. One suspects, or at least hopes, that this memoir, at once bleak, redemptive, annihilating and uplifting, will prove restorative and healing to its author. It is a fine tribute to a courageous father.

We jump regularly between childhood and adult life, bookended by the monumental return visit to a place that is both home and foreign. In a place suffused with sorrow he remains alive to moments of beauty.

A student of architecture, he admires the “cocktail of influences” in Benghazi – Arab, Ottoman, Italianate, European modernist – which suits this “relaxed, eclectic and rebellious” city. But all this is as nothing compared to Benghazi’s defining wonder: its light, so strong one can almost feel its weight.

The searcher for truth, especially when wounded, must don armour to pursue his quest. Matar is self-contained and self-reliant, suspicious of strangers and unsought sympathy. The mantra that sustains him, culled from one of his father’s short stories that is unexpectedly revealed to him during a public reading in Benghazi, is distilled into three words: “work and survive”.

His abrasive intelligence cuts through British officialdom and a Libyan regime manoeuvring like a knife. He is granted a meeting with the then foreign secretary David Miliband to discuss putting pressure on the Qaddafi dictatorship to reveal his father’s fate.

He receives a mild recrimination about “all the noise” he has been making, inconvenient when there are all those new energy deals to sign. Matar wonders whether Miliband is demonstrating the “genuine warm confederacy of a fellow Brit. Or maybe it was the impatient, political, bullying pragmatism of power”.

He gives a convincing portrait of Saif al Islam Qaddafi, the strutting Mini-Me of the regime’s latter years, whom he meets in London with the obligatory entourage of thugs and sycophants. Qaddafi Jnr, currently languishing in a prison in Zintan minus the finger he used to wag at Libyans on television during the revolution, manages to liberate Matar’s uncles and cousins after 21 years behind bars, but of Jaballa there is no news.

There are no answers here, just suggestions and probabilities. "Even today, to be Libyan is to live with questions." Jaballa Matar was likely killed by the regime on June 29, 1996, when about 1,270 prisoners at Abu Salim were massacred after a revolt. On the very same day in London, Matar had abandoned, after many years, his daily habit of looking at Velázquez's The Toilet of Venus in the National Gallery and, while the machine guns were doing their worst in Tripoli, had moved on to Manet's The Execution of Maximilian.

The separation of fathers from sons cuts men adrift in a sea where they must either sink or survive. As a writer reaches out for literary parallels to make sense of his predicament, so Telemachus, Edgar and Hamlet flit through The Return with their "private dramas ticking away in the silent hours", counterpart to those Matar has now made public.

“I am reluctant to give Libya any more than it has already taken,” he writes at the outset. No one could question that. Yet from the casual cruelty of the Qaddafi regime and the lacerating grief it produced, Matar has fashioned a great and lasting gift for an audience much wider than this. We must be thankful to him for that.

Justin Marozzi is a freelance journalist and author of Baghdad: City of Peace, City of Blood, winner of the 2015 Ondaatje Prize.