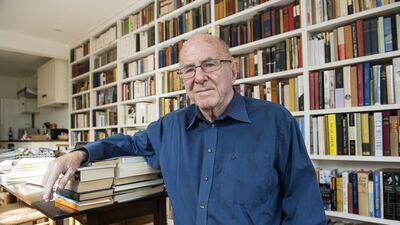

Clive James is the great appreciator of our time. Over the course of his career – which first took flight when The Metropolitan Critic was published in 1974, and in which he has worked as a novelist, poet, columnist, television critic, broadcaster, essayist, autobiographer, travel writer and translator – he has arguably done more than any figure of his generation to transmit to the reader, the viewer, the listener, his enthusiasm for the arts.

He has pursued this project at all cultural levels. The weighty novel, the satiric squib, the comic verse, the sedulously crafted lyric, the spine-tingling aria, the contagious pop song, the trashiest of trash television, the sweep and majesty of box set dramas – James treats them all with equal seriousness, equal care, equal love. And always he proceeds from the principle of enjoyment.

Much of James's own cultural enjoyment has come from television, and the record of this appreciation can in part be found in a series of wonderful pieces he wrote for the London Observer during his 10-year stint, from 1972 to 1982, as the paper's TV critic. Since then, he has continued to engage with and lose himself in the offerings of the small screen, indulging in late-night reruns, VHS videos and, more recently, collections of DVDs. Play All: A Bingewatcher's Notebook is in part a consideration of these developments.

It aims to evaluate the phenomenon of what James regards as today’s great televisual achievement: the grand and sprawling dramas that we tend to consume in the form of the box set.

The book begins where James's tenure at the Observer finished. By the time he had stopped contributing his weekly analysis of the nation's television, he had come to regard himself as an authority on the subject. He knew its strengths, weaknesses, limitations. He knew its history. He thought he could predict its future. And that thought provided the subject for his final column:

“I signed off with a confident prediction that although the American production centres... might go on picking up secondary earnings by flooding the world with stuff priced low because it had already made a profit in the home market, the droll sarcasm of the desk sergeant Phil Esterhaus (Michael Conrad) in Hill Street Blues would be about as clever as their effort would ever get. Seriousness, sophistication and the thrill of creativity could be supplied only by the older, wiser, more mature nations.”

Looking back on this spectacular error of judgement at the millennium, James “lashed” himself “for having so completely failed to guess what might happen to the American television output later on”. “It was,” he writes, “a punishing example of what ought to be a critical rule: if you can’t quell your urge to make predictions, don’t make them about the future.”

When in early 2010 a diagnosis of a “polite but insidious form of leukaemia” left James’s own future looking desperately attenuated and bleak, he decided to spend whatever time he had left reading, writing and indulging his “age-old, oil-burning TV and DVD habit” in the company of his younger daughter, Lucinda.

The experience of binge-watching the “new and often wonderful box sets” alongside “multiple rescreenings of the kind of old and not at all wonderful James Bond movie” prompted him to give an account of his response to the more recent televisual form, and to do so “in the context of the established brain patterns” of someone who still feels compelled to watch the TV of old.

James's summary of the book's objectives makes it sound more coherent than it is: for the most part its pages are free from concerted argument. But instead we get a series of ruminative and marvellously entertaining essays in appreciation of such shows as The Sopranos, The Wire, The West Wing, Game of Thrones and Battlestar Galactica.

James's considerations of these programmes feature many instances of penetrating and memorable cultural analysis: "Game of Thrones stands revealed as a crowd pleaser. To despise that, you have to imagine you aren't part of the crowd. But you are: the lesson that the twentieth century should have taught all intellectuals"; "One of the salient qualities of recent long-form television drama has been to employ the utmost sophistication to face us with the primitive; and to make us realize that civilisation has barbarism for a bottom level."

Not all of the book’s attempts to link television to the story of the struggle for civilisation are this compelling (I do not share James’s certainty that TV drama has been a force for good in securing equality for women). But they are always stimulating, and his discussions of the shows that populate the book are conducted in a mode that unites an acute critical intelligence with warmth, elegance and clarity of expression.

They are also amusing and witty ("Jon Hamm [Don Draper, Mad Men] is the actor with everything, except the sense to change his name") and characterised by an enthusiasm for creative endeavour that is inspiring and contagious.

Yet the book is not without shortcomings. James’s prose can sometimes be clichéd, and he has an off-putting tendency to dwell on the appearance of beautiful female leads. This, however, is a weakness he is aware of, and the awareness allows him to be funny about it.

As he says in one of the lovely autobiographical digressions that appear throughout the book: "I am pledged to run these remarks past the women of my family, and they still want to know why I, at my age, and in my depleted state of health, sobbed aloud when Zoe Barnes [House of Cards, played by Kate Mara] got pushed under a train."

Matthew Adams lives in London and writes for the TLS, The Spectator and the Literary Review.