Something extraordinary appears to be happening in the world of Chinese science fiction. In 2015, Liu Cixin's The Three Body Problem became a global bestseller and the first translated work to win the prestigious Hugo Award, sci-fi's equivalent of the Oscars. Last year, Hao Jingfang's Folding Beijing won Best Novelette at the Hugos, beating none other than Stephen King to the prize.

One could argue, on the other hand, that Chinese science fiction has been extraordinary for roughly a century now, both as propaganda and critique, and it’s the world that is finally waking up, much as it did when it discovered Scandinavian crime writing about two decades ago.

In either case, if anyone is ringing the alarm for English-speaking audiences, it is Ken Liu. Born in Lanzhou until moving to the United States when he was 11, Ken (pictured right) is a rising star in the science fiction firmament thanks to his self-proclaimed "Silkpunk" genre, a hybrid of Chinese and western epic forms: think Homer's Odyssey spliced with Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong.

In recent years, Ken has also become a translator of note, responsible for helping to bring both Liu Cixin and Hao to international prize-winning attention.

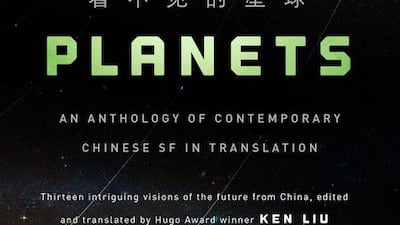

This ad hoc role as cheerleader for contemporary Chinese science fiction has just been reinforced by Invisible Planets, an anthology of recent short stories by the new wave. In addition to the frankly mind-bending Folding Beijing, we have works by Chen Qiufang, Xia Jia, Tang Fei, Ma Boyong and Cheng Jingbo. There are also illuminating essays by both Lius (Ken and Cixin), Xia and Chen.

Perhaps the first thing that struck me on finishing Invisible Planets was the sheer diversity of voices. While Chen's opening The Year of the Rat wouldn't look out of place in a horror anthology, Liu Cixin's The Circle reads like a modern update of a classic Chinese romance: a twisting tale of competing empires, political machinations and revenge, with some strange martial mathematics thrown in. Hao's chatty, pseudo-encyclopedic almanac of intergalactic civilisations that comprise Invisible Planets owes a debt to Italo Calvino's playful interplanetary fables, Cosmicomics, not to mention Douglas Adams's Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy.

Indeed, it proves easier to define the collection by what it doesn't do rather than what it does. Sci-fi commonplaces are either rare or quietly subverted. There are spaceships in Liu Cixin's witty Taking Care of God (21,530 to be precise), but they merely deliver the put-upon gods who wash up, cook terrible food and play chess with an irascible grandfather. The robots in Xia's Tongtong's Summer are similarly domestic, and more Mrs Doubtfire than Terminator.

With the exception of Cheng's Grave of the Fireflies and Hao's Invisible Planets, most works take place in societies not unlike our own. The hero of Ma's The City of Silence may live in 2046 (a nod, perhaps, to Wong Kar-wai's film of the same name), but his life mapped on a highly-regulated internet feels eerily similar to our own: "Now that the web was almost equivalent to daily life, it was necessary to be ever vigilant" applies as much to us as Ma's isolated, paranoid future-beings.

It is tempting, perhaps too tempting, to treat plots like this as thinly-veiled critiques of contemporary China. What else are we supposed to do with Folding Beijing, which re-imagines China's capital as a collapsible Rubik's cube that separates the rich from the poor, the connected from the untouchable, the necessary from the expendable?

It is hard to ignore the examination of China's deepening population crisis in Tongtong's Summer: eerie human robots take care of China's rapidly ageing population, who, thanks to the one-child policy, vastly outnumber their harried, over-tired children. Elsewhere, I glimpsed portraits of migrant workers, environmental collapse, unemployment and guanxi, China's system of political patronage.

Then again, just as many stories self-consciously resist such narrow interpretation. Grave of the Fireflies reads like a fantasy folk-tale re-imagined by Jorge Luis Borges or Calvino. Rosamund is an orphaned girl marooned in an unstable post-apocalyptic world filled by ghosts, wizards and a path to another world. When she isn't wondering why the stars are dying, she utters lines that feel both ancient and modern: "Mankind streamed across the river of time, aiming straight for the Door of the Summer."

What does connect many of the works are the ways in which profound human emotion inserts itself into even the most generic narrative. The Year of the Rat might read like Aliens crossed with James Herbert's Rats, but it evokes pathos in the most unexpected places: the vulnerable, misunderstood character Pea cradling a baby rodent; the screams of rat parents as their offspring are murdered; the sight of millions of man-made creatures marching to their deaths.

Tongtong's Last Summer begins as a black comedy, but ends by creating a delicately heart-warming alliance between youth and age.

Most striking of all is Tang's Call Girl, which sabotages our presumptions when we realise Tang Xiaoyi seduces only through stories: "The air feels thin; the sunlight seems harsh; a susurration fills his ears. He has trouble telling the density of things. This is another world."

Almost every work in Invisible Planets works similar magic, transporting the reader from the everyday to another world that is, by turns, frightening, unsettling, familiar and strange. If this is a snapshot of Chinese science fiction, the complete picture is very bright indeed.

James Kidd is a freelance reviewer based in London.