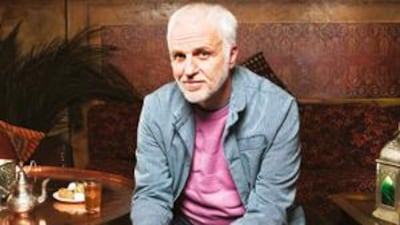

Mourad "Momo" Mazouz is not happy. "You don't know it, but I'm in agony," he declares emphatically, his saturnine face even glummer than usual. "I feel sick." The problem is not, happily, my interviewing technique, but the numerous flaws he has detected in the service and fitments of the restaurant that carries his nickname. We are sitting on the terrace of the acclaimed Moroccan-themed Momo, which is situated just off Regent Street in central London, but feels like the middle of Marrakech. A buzzy lunchtime crowd is fuelling up on spiced chickpea soup and lamb patties; the air is thick with cigarette smoke and steam from mint tea. It is a sight to delight any restaurateur, particularly in the throes of a recession.

But all Mazouz can see is the dust lurking in a corner of the engraved metal table-top, the spoon placed on the wrong side of my saucer, the unattractive rear view of a brass tray that's propped against the till. "I don't need to look at that!" he barks in his unreconstructed French accent, and a waiter hastily removes it from sight. It is one of the odder contradictions surrounding the man that although he's made his name with a clutch of laid-back, relaxed restaurants and bars that draw the cool crowd - Almaz in Dubai, 404, Andy Wahloo and Derriere in Paris, Momo and Sketch in London - he is a nit-picking perfectionist.

"This is a tough job," he says. "Nobody wants it. People who do it are completely run down by the age of 70. Every day there are tons of problems: the toilets, the drains, the clients, the staff… and the more restaurants you have, the more problems you have." In which case, he must be a glutton for punishment. Right now, he's creating a new Moroccan French restaurant in Beirut. "The people there are very educated," he explains, cheering up again, "and it's an interesting city, politically speaking, which makes it tricky and attractive. And you meet gorgeous, open, generous people. But they do not eat sardines. I don't know why, but I will make them eat sardines. It is the best fish in the world."

Mourad Mazouz has never been one to run from such challenges. On the contrary, he revels in them. He could undoubtedly have made himself a millionaire many times over simply by replicating the haute-casbah formula of Momo and 404 around the world, but the idea fills him with horror. "I am not looking to expand," he says. "I don't want to reproduce. What I like is to create." It is telling that he had, he says, around 80 offers to set up restaurants in Dubai. But what appealed to him about the concept of Almaz, which is backed by the chairman of Al Tayer group Obaid Humaid al Tayer (now the Minister of Finance), was that it had to be alcohol-free and sited in the Mall of the Emirates - the very antithesis of the sybaritic creations he'd become famous for.

"It was not me," he says. "And then I thought, why not? It could be fun, it's a great challenge. So I spent some time in Dubai and I saw that nobody had thought to make a high-profile restaurant for the locals - they were all designed for tourists, with alcohol." The resulting concept, which consists of several spaces including a fine-dining restaurant serving non-alcoholic champagne, a relaxed Moroccan café, a patisserie and a sheesha room, has received rave critical reviews. So successful is Almaz that Mazouz has been having meetings with the Ministry of Culture, which wants him to set up a restaurant of Emirati cuisine and produce an accompanying cookery book.

"But with the recession, they have other priorities," he explains. "And the politics have become a little much. People were complaining about a foreigner writing on the national cuisine, so I am putting it on hold." Meanwhile, Mazouz has got plenty other projects on his plate. Aside from the Beirut restaurant, which is planned for February next year, there's the recently launched Double Club in north London to run.

The brainchild of German contemporary artist Carsten Holler, the man who put slides into London's Tate Modern art gallery, the Double Club has a menu that is half-western, half Congolese, and is intended to bring about dialogue between the two cultures. It's a restaurant-cum-nightclub-cum-art installation, and 50 per cent of the profits go to a charity to help Congolese women victims of the armed conflict.

Mazouz has been recruited to run it, which means that although the restaurant was planned only to have a six-month lifespan, the food critics are calling for it to be a permanent addition to the London restaurant scene. There's his new record label, Mo-Zik, to think about, not to mention giving Momo a re-vamp and getting rid of those dusty tabletops and unattractive tray-backs. And finally, his Lebanese/French girlfriend Caroline is expecting their second baby, a girl, in October. Mazouz already has two sons, Elyas, who is three, and Lounes, 19, from a previous relationship.

"I said, 'Oh, no, not again,'" he tells me, gloom descending again at the prospect of impending fatherhood. "I will be 67 when my daughter is 20. And it's a big responsibility." Responsibility is something he can't avoid as both parent and employer, but he clearly rather resents it. He is resolutely rootless. The idea of marriage appalls him, his London flat is rented, and the only property he owns is a cave in Morocco that faces on to the Atlantic.

"I bought it from some fishermen with a friend of mine, and we know that in a couple of years we will have to give it up because it's in a national park and we're not allowed to own it. That is why I bought it," he explains. "I don't have a home. If you ask me tomorrow to move to Buenos Aires or Istanbul, I can." As for his bank account, it is empty, a result of his decision on a whim to start up Sketch in a gigantic 18th-century town house in the West End of London. For nearly a century, it had been the headquarters of the Royal Institute of British Architects. But by 1999, when Mazouz and his then business partner, Claude Challe, were looking round the neoclassical building, it had begun to crumble. Encouraged by Challe, Mourad bought the 1,200 square metre space, borrowing several million pounds to do so.

Having redecorated in surreal and costly style, with bronze-coloured resin dripping down the stairs and lavatories in egg-shaped pods, he then discovered that the giant building was collapsing. The rebuild cost a further £6 million (Dh 33million), and when it opened in 2002, although the interiors magazines called it the "new Xanadu", food critics slammed the restaurant, overseen by the Michelin-starred Pierre Gagnaire, as pretentious and overpriced (famously, one starter cost £70 (Dh383)).

Sketch is still clearly a huge drain on Mazouz's purse and energy - he came up with its name, prophetically, because he said it would always be a work in progress. "I don't regret Sketch for a minute," he says, "but I wish I didn't have this debt. I owe millions and I haven't a penny in my pocket." So why doesn't he sell up and relax a bit? "I don't create to sell. What for? Why do I need money?"

On the contrary, he says he sometimes wishes Sketch would bankrupt him. "Then I would have more time for my friends." But surely it would be just a matter of weeks before he started a new restaurant? "This is my work," he agrees with a sigh. "I am a worker. I was raised as a worker. If you put me on a desert island, in six months' time I will have built a restaurant." Unsurprisingly, given his life philosophy, Mazouz is not a great believer in legacies of any description (he treats me to a long diatribe on the follies of inheritance).

Still, it seems clear to me at any rate that both his compulsion to roam and his work ethic are undoubtedly a result of the way he was brought up. Mourad Mazouz was born in Algeria in 1962, the year the country won its independence from France. His father, a chef de servis, was Algerian, of Berber descent, and his mother was French. When their son was six they separated and his mother returned to Paris.

He seems to have brought himself up, roaming the streets and getting into fights. As the "French boy", he was the target for much bullying, and learnt to give as good as he got. ("If someone says you are the son of a French, you take a stone and you smash his head.") Sometimes he wouldn't see his father for days, which is not so surprising when you consider that the family home was shared with 72 first cousins.

At the age of 15, he left to visit his mother in Paris and never went back. For three years, he worked as an office cleaner, then a music PR, and at 20, left for America where he found work illegally at Ma Maison, an LA hot spot. After five years travelling around America, Asia and the Caribbean, he was deported to France. That was when he decided to open his first restaurant, borrowing the start-up capital from four friends.

In 1988, aged 26, he launched Au Bascou, principally in order to fund his nightclub habit, and immediately found his métier. Au Bascou was named Bistro of the Year, and brought in enough money for Mourad to start 404 in a rickety Marais town house two years later. "It's been going 19 years," he says proudly, "and we've never had a free table." The Midas touch hasn't failed since. So what is his ambition, I wonder?

"I have no ambition," he shrugs. "I don't know what I'm doing next. Why should I have ambition?We are born, we die, what's the point?" He takes a reflective sip of boiling mint tea. "My dream," he goes on slowly and bathetically, "my dream is to have time to watch TV. I love television." Unfortunately, with a burgeoning restaurant empire to run, and wealthy investors across the globe clamouring for his services, Mazouz's longed-for couch-potato lifestyle is likely to remain forever fantasy.

Try these simple and delicious dishes, taken from the Momo menu Fennel and courgette compote with aniseed Serves 4 as a side dish 6 fennel bulbs 4 courgettes 3 tbsp olive oil 1 tbsp aniseeds 20g unsalted butter 1/2 tsp salt 1/2 tsp ground white pepper Clean the fennel bulbs, removing all the hard parts, and chop finely. Cut the courgettes into 1cm cubes. Heat 2 tsp olive oil in a large pan, add the chopped fennel, reduce the heat and stir. When translucent, cover the pan and leave to cook on low heat for 35 minutes. Stir occasionally.

Meanwhile, heat another spoonful of oil in another pan and fry the courgettes while stirring, on medium heat, for five minutes, without browning. Ten minutes before the end of the fennel's cooking time, add the aniseed and the courgettes. Stir gently but thoroughly and uncover the pan for the rest of the cooking time to allow for complete evaporation. Off the heat, add the butter, cut into small pieces, and the salt and pepper. Stir and serve hot.

Confit of duck tagine with pears, figs and glazed carrots Serves 4 as a main course 4 pieces confit of duck 75g unsalted butter 50g sugar 3 pears, peeled, cored and cut into quarters ground cinnamon 15 large fresh figs 4 onions, finely chopped 100ml duck or chicken stock For the glazed carrots: 3 large carrots 25g unsalted butter 50g brown sugar 1/4 tsp salt Put the pieces of duck in a covered pan on low heat for 10 minutes to melt the fat round them, then drain them thoroughly to remove excess fat. Reserve the fat.

Heat 50g of the butter in a pan, add the sugar and start a caramel on low heat. Once brown, coat the quarters of pears with the caramel and sprinkle cinnamon over them. Wash the figs and remove the stalks, without peeling them. Cut four figs in quarters and put them aside. Dice the rest of the figs. Put the remaining butter (25g) in a large pan together with the onions and cook, covered, for 10 minutes, stirring occasionally. Then add the diced figs and stir with the onions. Cover with the duck stock and leave to cook, uncovered, stirring occasionally, until reduced to a soft compote of an even consistency, but not dry.

Slice the carrots diagonally. Put them in a small pan, add water, to cover, and the butter, sugar and salt. Leave the carrots to cook uncovered on a low heat until the water has evaporated completely. Heat 3tbsp of the duck fat in a frying pan on a very low heat and put in the fig quarters, on one side. Add a pinch of sugar and cinnamon on the top side of the fig quarters and fry for one minute. Turn the quarters to the other side, sprinkle with another pinch of sugar and cinnamon and fry for one minute.

Serve in individual warm tagine plates, first dividing the fig and onion compote between the tagines, then putting one piece of duck, completely drained from its fat, on top of the compote. Around the duck, arrange the glazed carrots and put three of the caramelised pear quarters in a dome shape. Finally, add 4 fig quarters to each tagine. Sprinkle the whole dish with a little more cinnamon. Cover each tagine and heat it for two minutes. Serve very hot.

Couscous seffa Serves 4 (pictured above) 200g white seedless raisins 1 litre warm, unflavoured tea (weak Ceylon, no milk, is fine) 500g medium-grade couscous 800ml water 1/2 tsp salt 80g unsalted butter, cut into pieces 80g icing sugar 100ml orange-blossom water 1tbsp ground cinnamon 1 litre buttermilk (optional) Soak the raisins in the warm tea and leave to swell for an hour. Drain and set aside. Steam the couscous according to the instructions. Add the sugar, orange-blossom water, three-quarters of the cinnamon and the raisins to the couscous and mix thoroughly. Sprinkle with the remaining cinnamon and serve warm. Serve with buttermilk, if using, in a carafe.

Dried fruit salad with aromatic spices Serves 5 100g stoned prunes 100g dried apricots 100g dried figs 90g blanched almonds 90g walnut halves 50g sesame seeds, toasted, to decorate For the syrup: 1 litre water 150ml orange-blossom water 150g brown granulated sugar 5 cloves 2 cinnamon sticks 1/2 tsp grated nutmeg Juice of 2 limes To make the syrup, bring the water to the boil and add the orange-blossom water and sugar. Reduce the heat to very low and add the cloves, cinnamon sticks and grated nutmeg. Cook gently for one hour. Leave to cool, then add the lime juice and stir.

Toast the almonds in a dry frying pan. Put the three dried fruits in a large bowl, and pour the syrup and spices on top. Cover with cling film and leave the fruits in the fridge overnight to macerate, giving the syrup's aromas to the fruits. One hour before serving, add the walnuts and almonds. Remove the cinnamon sticks and the cloves. Serve the fruits in the syrup after sprinkling the fruit salad with toasted sesame seeds, just before serving.

Recipes taken from The Momo Cookbook by Momo Mazouz (Simon & Schuster)