In the early 1990s, a Chilean teenager – like every other Chilean teenager – sat down to take the Academic Aptitude Test. A stultifyingly boring multiple-choice exam – and the stuff of student night-mares the world over – it does not sound like the starting point for one of the most intriguing books of 2016, let alone its whole premise.

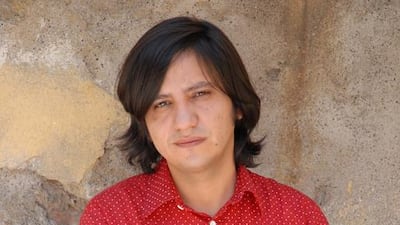

Yet that is exactly what Chilean writer Alejandro Zambra decided to try when he got bored of writing a conventional novel. He remembered the test he took as an 18-year-old and wrote the whole of Multiple Choice in its style and format. That genuinely means pages of questions and answers, lists and tick boxes.

“It was a really crazy idea,” he says with a laugh. “But I immediately knew I could go somewhere if I followed this road – I just didn’t know where it would lead.”

So yes, flick through the first few pages of the test and it might seem like a grand folly, a terribly postmodern literary exercise. But Multiple Choice is so much more than that. Slowly, but surely, the questions and potential answers reveal uniquely profound takes on life in Chile under the dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet – both funny and melancholic.

Zambra quickly found out that for all its playfulness, the structure caused him almost as many problems as a more straight-forward novel.

“It was like learning to play a new instrument that you really dislike,” he says.

But it was worth sticking with, as the format was able to take him in directions a traditional novel never could. For example, there is a really telling section in which the reader is asked to delete sections of text so that a story makes sense. Immediately, the subtext of life under Pinochet’s censorship becomes clear.

“Even at the time, it was impossible not to think that the regime was teaching you to be a censor,” he says. “It’s interesting how authority and authoritarianism almost contaminate the word ‘author’. They suggest the author always has the power, but for me writing is actually about losing control.

“It’s in those moments of writing when you are not thinking at all that you find things inside you that you didn’t know were there.”

Still, for all his complicated theories about the nature of reading and writing, Multiple Choice is a remarkably engrossing, even moving, book.

Sometimes, Zambra plays with the very idea of a set of multiple choice answers, listing the same “choice” five times. That might seem just a little silly, but pause to think – which this book encourages time and time again – and there’s real pathos in this seemingly throwaway section.

“This idea of the single answer really interested me,” says Zambra. “Because there are moments in life where you need a single answer to exist. Sometimes, multiple choices can be overwhelming – you want to know what to do.

“And then there’s also the sense that a dictatorship wants you to think there is only one answer.”

In another part of the test, the reader must put choices in the best order to form a coherent text. It is here that Zambra’s suggestion that the book is poetic makes sense. For all the plainness of the prose, read aloud this exercise and it almost takes the form of a sonnet. It is also heartbreaking.

"Multiple Choice is definitely sadder than it initially was," he agrees. "As I wrote it, I began to realise that all life is on a knife edge – although I'm really wary about proposing a message for the book. For me, literature shouldn't be about single ideas. Genuinely, I think you can destroy your own writing by talking about it too much."

So it is left to readers to try to work out exactly what this strangely moving and unique book really means.

One thing is for sure: although it will undoubtedly get filed under “experimental fiction”, it feels accessible, readable and genuinely interactive.

“All good literature is experimental anyway,” Zambra says. “I know this is experimental in a very explicit way but I’ve also noticed people writing their choices in the book, which I love.

“I think that shows that you can just read it, and it does work, even with people who might not be into literature.”

All of which leaves one final question for Zambra to answer. On the cover there is one further multiple-choice question. It is, amusingly: "Is Multiple Choice (A) fiction (B) non-fiction (C) poetry (D) all of the above (E) none of the above." Tellingly, not even Zambra can answer that.

“Do I call it a novel?” he ponders. There is a long pause.

“It needed to be more savage and crazy than a novel with repeating characters. It’s maybe more related to poetry, although it’s not a poetry book. So it’s probably best not to put a label on it. Call it… a book.”

• Multiple Choice is out now

And in more book news

A wizard idea

Talking of public transport, actress Emma Watson left copies of her latest book club selection, Maya Angelou’s Mom & Me & Mom, on London’s Underground for commuters to read last week. Part of the Books On The Underground campaign, which encourages readers to find a book on the Tube, read it and then leave it for someone else, there’s even a way of getting hold of a copy signed by Watson if you live nowhere near London or even the UK: just go to http://booksontheunderground.co.uk and follow the link to the competition. Be quick, the closing date is November 11.

Training sights on children’s fiction

Thomas The Tank Engine fans might want to look away now. Although the new illustrated book by Beryl Evans, Charlie The Choo-Choo, might seem innocuous enough, one glance at the author quote on the front should be enough to suggest all is not quite as it might seem. “If I were ever to write a children’s book, it would be just like this!” exclaims horror author Stephen King. Which is certainly accurate - Beryl Evans is his pen-name for this nightmarish picture book out on November 22. Let’s just say he’s likely to derail any notions of a happy adventure on the St Louis to Topeka line.

Crossing the line

The old argument about whether timely stories are opportunistic or important was rehearsed again this week with the news that army veteran turned writer and author Elliot Ackerman will set his new contemporary love story on the Turkish/Syrian border during the rise of Islamic State. Still, if anyone can write coherently about the troubles in that region it’s Ackerman, who has lived in Istanbul for some time and brought a rare insight into the war in Afghanistan in this year’s debut Green On Blue. Dark at The Crossing is published in the US in January and worldwide in April 2017.

artslife@thenational.ae