July 2004. My first encounter with Baghdad. The airport is a white blaze of hot metal and blinding light. Palm trees swirl through shimmering waves of heat. Black Hawk helicopters overhead. A car park filled with armoured four-wheel drives, bodywork boiling in the sun. Groups of security teams wait for their passengers. Guns and sunglasses. Sirens in the distance. Sporadic gunfire. Grit in my mouth, eyes and ears. Sweat pouring down my back. Fear in my stomach. A fury of noise, heat and light.

I have just accepted a position with a British security company in Baghdad. My job title is director of civil affairs. It will involve political liaison and launching a nationwide programme of community projects. Clean drinking water for schools. Supplies for hospitals. Generators. Inoculations. I’m not thinking of any of that right now. I’m wondering if we will even make it to the Green Zone. I’m thinking about the recent spate of attacks by “the bad guys” and how our armoured vehicle offers no protection against suicide car bombers. I’m remembering newspaper articles describing our route into town as “the most dangerous stretch of road in the world”.

While I wiped the sweat away from my eyes, I didn't think for a moment that for much of the next decade I would be living and working in Iraq, researching the first English-language history of Baghdad for almost a century.

A serendipitous conversation with my agent, and the almost simultaneous discovery of the British writer Richard Coke's book, Baghdad: The City of Peace, persuaded me that it was time to revisit this great city with a full-length biography.

Coke’s history was published in 1927, the year after the formidable British official Gertrude Bell died. How much had happened since then! Three Iraqi kings had come and gone. Then there was the brutal revolution of 1958, ushering in a new era of republican turbulence and violence that led, in turn, to the Baathists and Saddam Hussein. The Iraq-Iran War of the 1980s, the First Gulf War, a decade of annihilating sanctions, the Second Gulf War and the explosive rise of Al Qaeda …

Research started. I buried my nose in all the books I could get my hands on, working closely with an Iraqi historian of Baghdad who became a dear friend. I visited ancient Abbasid sites with another friend from Baghdad University, interviewed professors and politicians, archaeologists and museum chiefs, ordinary men and women, displaced Iraqi Jews, the beleaguered Christian community. I delved into Abbasid scientific manuals, Iraqi histories and memoirs, Ottoman archives, medieval travellers' tales, the Arabian Nights and contemporary reportage to build a rich, many-layered portrait of this extraordinarily resilient city.

I wanted to tell the whole story of Baghdad, from its foundation in AD762 to the present day. To begin at the beginning is to explore Baghdad’s greatest half-millennium, when it was the richest, most sophisticated and advanced city on Earth under the rule of the Abbasid dynasty of caliphs, leaders of the Islamic world.

Perhaps nowhere else on earth has world civilisation flourished so extraordinarily, in such a short period of time, as in Baghdad during the earliest years of the Abbasid caliphate, which lasted from AD750-1258.

Basking in prodigious royal patronage, the City of Peace – as Baghdad was known after a sura in the Quran about Paradise – was fabulously rich from its very foundation in 762. The astronomical sum left in his treasury on his death in 775 by the caliph Al Mansur, the founder of Baghdad – 14 million dinars and 600 million dirhams, or around 2,640 metric tons of silver – demonstrates how quickly his city had prospered and how rapidly the Abbasid dynasty had consolidated its position at the heart of the Islamic Empire after the defeat in 750 of the Damascus-based Umayyads.

Swishing through their ornate palaces in embroidered silks, the royal family sat at the top of the social and political hierarchy, luxuriating in the trappings of power. Abbasid courtiers and favourites, famous singers, beautiful slave-girls and wine-quaffing poets also grew rich on the vast pickings available from the caliph’s court, where life-changing fortunes could be made in a moment at the ruler’s whim and just as quickly, sometimes fatally, lost.

Beyond this glittering and unpredictable world of imperial largesse, trade also fuelled the rise of Baghdad. Vessels plied the lengths of the Euphrates and the Tigris rivers, sand-blown caravans trudged from Egypt and Syria, boats and beasts of burden respectively bringing their wares to the new city whose population rapidly learnt the delights of conspicuous consumption.

Within a few years of its foundation, the city’s markets were teeming with merchants selling the products of the world, from silks, gold, jewellery and precious stones to books, spices, exotic fruit, exquisite carpets, horses and camels. Within a dozen years a property boom was in full swing, as thousands poured in to speculate and make their fortunes. Mansur’s fledgling capital grew into a mighty metropolis and unrivalled trading emporium, a Rome of the East.

Peace brought plenty. With Baghdad at its centre, the province of Iraq generated four times as much tax to the exchequer as Egypt, the next richest province in the empire. Each year it paid a staggering 160 million dirhams – or about 480 metric tons of silver. Culture required leisure, leisure required wealth and wealth flowed from patronage and a booming economy.

Flush with money, Baghdad presided over a cultural revolution that was every bit as remarkable as its pre-eminent political and commercial power. Poets and writers, scientists and mathematicians, musicians and physicians, historians, legalists and lexicographers, theologians, philosophers and astronomers, even cookery writers – all made this a golden age. More scientific discoveries were made during the ninth and 10th centuries than in any previous period of history. In short order, Baghdad became the cultural zenith of the Islamic world and the intellectual capital of the planet.

The outward-looking, intellectually inquisitive attitude of this time was encapsulated in one of the famous hadith of the Prophet Mohammed: “Seek knowledge even to China.” This insatiable quest for knowledge was one of the hallmarks of the Abbasid age. When the Umayyads fell, Arab knowledge was confined to Arabic grammar and poetics; Quranic exegesis; the collection of oral information about the sunna, the religious practices and traditions of the Prophet and the Islamic community; guidelines governing appropriate behaviour for the model Muslim; and a moral, ascetic mysticism.

The Abbasid achievement of generating new and lasting knowledge across many disciplines, from science and law to poetry and mathematics, represented a boundless new universe. No wonder the 10th-century geographer Muqaddasi called Iraq “the fountainhead of scholars”. The movement of great minds to Baghdad was as extraordinary a phenomenon as the sweep of Arab horsemen from the Arabian desert during the world-changing conquests of the seventh century.

Securing the caliph's patronage was the quickest way for any ambitious poet, scholar or musician to get on in Baghdad. While poetry flourished, the rise of prose was given an electrifying boost by Al Jahiz, who gravitated to Baghdad in the early ninth century under the intellectually appealing caliphate of Mansur's great-grandson, Al Mamun. His best known work among 231 titles was Kitab al Hayawan, the encyclopaedic seven-volume Book of Animals, which drew heavily on Aristotle. Some argue it contained the seeds of Darwin's much later theory of natural selection. The breadth of his writing was typically Abbasid, ranging from the superiority of black men over whites, pigeon-racing, miserliness and the Aristotelian view of fish.

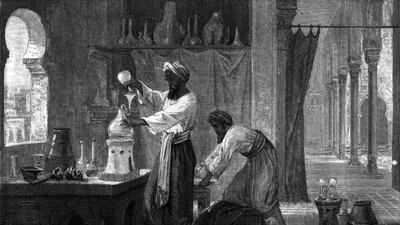

Abbasid Baghdad wasn’t all poetry, prose and music. In the ninth century the city also emerged as the scientific powerhouse of the world. The famous Bait al Hikma, the House of Wisdom, became the nerve centre of Abbasid intellectual activity, a combination of lavishly endowed royal archive, learned academy, library and translation bureau, with a staff of scholars, copyists and bookbinders. By the middle of the ninth century, it was the largest repository of books in the world, the seed from which the golden age of Arabic science flourished.

Other individuals also made profoundly important contributions: the Banu Munajim, a courtly family of astronomers and astrologers, opened the Khizanat al Hikma, the Treasury of Wisdom, a library-cum-hostel for scholars. The trio of deep-pocketed Banu Musa brothers, Mohammed, Ahmed and Hassan, built on the foundations laid by the classical world with their work in geometry, astronomy and engineering, commissioning expeditions from Baghdad to Byzantium to bring back new manuscripts for translation and employing teams of translators on fabulous salaries of 500 dinars a month – something like Dh95,000 today.

Mohammed ibn Musa Al Khwarizmi, a master of arithmetic and astronomy, towered over the scientific field. His groundbreaking work Al Kitab al Mukhtasar fi Hisab al Jabr wal Mukabala (The Compendium on Calculation by Restoring and Balancing) bequeathed the dread term algebra, scourge of children's school days for more than 1,000 years, and was also a key conduit for the passage of Arabic numerals into the medieval West. Another of his works took advantage of the more advanced Indian system of reckoning made available to Baghdad's translators and introduced for the first time the decimal system of nine numerals and a zero. Within a century it led to the discovery of decimal fractions, which were then used to calculate the roots of numbers and calculate the value of pi to 16 decimal places. Those who would prefer to forget the horrors of quadratic and linear equations can remember Al Khwarizmi instead in the word "algorithm".

Al Mamun wanted to test the accuracy of the ancients’ measurement of the world’s circumference at 24,000 miles, so off trooped the Banu Musa to the level plain of Sinjar, north-west of Baghdad. There they hammered in a peg attached to a line of cord after measuring the altitude of the Pole Star, and walked due north in a straight line, fastening new pegs and cords as the lines ran out, until they reached the spot where the elevation of the Pole Star had risen by a degree. The distance between the first and last points was 66 and two-thirds miles. The process was then repeated to the south. Since each of the 360 degrees equated to 66 and two-thirds miles, the circumference of the world was therefore 24,000 miles, exactly as the ancients had calculated (the precise figure is actually 24,902 miles).

With science on the march, the time was ripe for Al Mamun to commission his famous world map. The Atlantic and Indian oceans became open bodies of water, rather than Ptolemy's landlocked seas. The length of the Mediterranean was refined to 50 degrees of longitude (Ptolemy had estimated it at 63 degrees), much closer to the true figure. Surat al Ardh (Picture of the Earth), a treatise from the same time, detailed the latitudes and longitudes of more than 500 cities, categorising towns, mountains, rivers, seas and islands in separate tables, each with precise co-ordinates in degrees and minutes.

In medicine Nestorian Christians, together with their Muslim descendants, held sway, none more illustrious than the precociously talented Hunayn ibn Ishaq, the head translator in the House of Wisdom and chief doctor to the ninth-century caliph Mutawakkil. At the age of 17 he translated On the Natural Faculties, one of many titles by the second-century Greco-Roman physician Galen, whose scientific theories dominated European medicine for 1,500 years. Hunayn went on to translate more works by Galen and Hippocrates, which were among his most lasting contributions to medical science. A distinguished scientist and author in his own right, his Ten Treatises on the Eye includes one of the first anatomical drawings ever of the human eye and is considered the first systematic textbook of ophthalmology.

Another giant in the medical world was Razi, the 10th-century physician and philosopher, the author of numerous medical tomes. Known more widely in the West as Rhazes, today he is considered the greatest physician of the medieval world. His classification of substances into the four groups of animal, vegetable, mineral and derivatives of the three, outlined in Kitab al Asrar (Book of Secrets), was a departure from the mysteries of pseudo-philosophical alchemy in favour of laboratory experiment and deduction, preparing the way for the future scientific classification of chemical substances. In Al Shukuk ala Jalinus (Doubts about Galen), Razi gave short shrift to the Greek theory of the four humours. His understanding of the nature of time as absolute and infinite, requiring neither motion nor matter to exist, was also far ahead of its time and has been likened to Newton's much later theories.

In the midst of this intellectual ferment in Baghdad, the Arabs for the first time explored philosophy. Abu Yusuf Yaqub Al Kindi, the pioneering, ninth-century Philosopher of the Arabs, led the charge. Al Kindi, a tutor to the caliph Al Mutasim's son Ahmed, sought to harness Greek knowledge, especially Aristotelian philosophy, to develop Islamic theology. It was he, more than any other scholar, who was responsible for introducing Greek philosophy to the Muslim world. An open-minded thinker, he embraced a rational approach to religion that made him enemies among the less intellectually adventurous. He was the prolific author of 250 works, from his landmark treatise On First Philosophy to writings on Archimedes, Ptolemy, Euclid, Hippocratic medicine and, as if that were not eclectic enough, glass manufacture, music and swords. Today his name is celebrated in Baghdad's Al Kindi Teaching Hospital in Rusafa, north-east of Al Rashid Street.

The glories of the Abbasid era are a distant memory in today’s Baghdad, where the City of Blood epithet is more appropriate than its traditional name.

Since the great Abbasid monuments were built from mud brick, unlike the stone of neighbouring Syria, they were destroyed in successive centuries by the flood-prone Tigris. Virtually nothing survives. Visitors searching for a tangible Abbasid legacy in Baghdad must take their lives in their hands and head to one of the city’s most magnificent monuments, a rare, heavily restored architectural jewel in Baghdad’s Old Quarter behind a sky-grazing portal of exquisite inscriptions and geometric motifs. Founded by the penultimate caliph Al Mustansir in 1233, the Mustansiriya is revered by Baghdadis as the oldest university in the world.

I visited it one morning in an adrenalin-filled sortie into town. “Imagine, this is all that remains,’ said my friend Thair, an academic at Baghdad University. “But look how beautiful it is and you can understand how great the Abbasids were.” He was right. In a city in which violence has been endemic from the very beginning, there is a serenity about the place that stems from an architectural style that marries simplicity with silencing grandeur. Defiance, resilience and nostalgia, quintessential aspects of the Iraqi character one could argue, are set in every stone.

Justin Marozzi is a writer and historian who spent much of the past decade in Baghdad. Most recently he has been based in Mogadishu as a communications adviser to the President of Somalia.