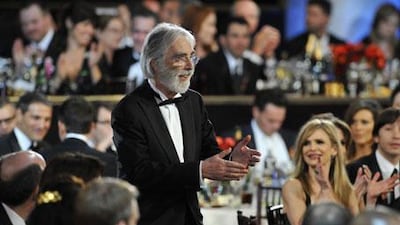

Michael Haneke is collecting prizes. In January, the Golden Globes awarded his latest film, The White Ribbon, the accolade of Best Foreign Language Film. The trophy will have to share space on the mantlepiece next to the Palme d'Or, which Haneke picked up in Cannes for his work on the black-and-white village drama. Among the other honours the film has received are Best Film, Best Director and Best Screenwriter at the European Film Awards, and the FIPRESCI (International Federation of Film Critics) Grand Prix for the best film of the year.

Haneke might have missed out on the Bafta for Best Film Not in the English Language in February, but few would count against him holding aloft a little gold statuette at the forthcoming Academy Awards. Recent history has demonstrated that Oscar voters have a fascination with work that deals with the Second World War and so there's a strong possibility that the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar will end up in either his Paris or Austrian home.

Not that the director is complaining: contrary to the usual show of modesty in which filmmakers claim that prizes mean nothing, he feels that winning awards is important. "You are only as good as your last film," he says. "If your last film was not successful, you will have less money for the next one. If it is successful you will have more money for it - that is the same for everyone after all. So you are always happy with success in that case and also prizes. The other thing is that it also increases the audience interest in the films and that is important."

The White Ribbon is set in 1913, but as the schoolteacher who acts as a narrator reveals in his introduction, it's the events that happened in Germany in the following decades that the film is trying to comprehend. The characters are referred to only by their occupation (a baron, pastor, steward, schoolteacher, midwife and farmhand) in an attempt to discover the features of German society on the eve of the First World War that may have led to the rise of Hitler and the Nazi Party.

But Haneke's film never tries to provide a direct chronological or political link between the goings-on in the small village community in the film and the rise of Nazi Germany. Instead, it's about the general malaise that underpins society and allows humans to do evil. The 67-year-old director explains: "What the film is trying to do is show the conditions in which people are prepared to follow an ideological position. It doesn't really matter in the first place whether it's a religious ideology, an ideology of the left or the right - that is not what is the important question. The starting point for all of this is some hopeless and humiliating position that people find themselves in and then along comes a ratcatcher who offers them a way out. Whether it is a German fascist or a Stalinist, that is another question entirely. The example of German fascism is simply the most obvious one and that is why I chose it."

The title refers to the white ribbon tied around the arms of the children in the village to show they are pure and innocent. It's a protection device that is futile in a society where adults do not lead by example. This becomes apparent as a string of unfortunate events befall the community, starting with a horse being killed by someone putting a wire across a gate. As more tragedies occur in the community, attention turns to the children. But are they villains or victims?

"On the scale of power, children are at the bottom of the pile. They are the predestined victims," says the director. "Below them are animals and that is why I have a lot of animals in my film. You can see how the hierarchy of violence works. That is why women always have the best roles as well. Victims are invariably the best subjects and heroes are always boring." This sentiment is evident in some way in all 10 of Haneke's films made for cinema (it is generally stated that he's made 11 feature films, but in fact The Castle was made for TV). He gives the clear impression that humans are incapable of learning from past mistakes, ensuring the cycle of violence continues. The metaphors are not always obvious. In 2005's Hidden, Daniel Auteil and Juliette Binoche play a middle-class couple who are sent mysterious videotapes that show them going about their lives. Auteil, through a feeling of guilt, believes that these tapes have something to do with his Algerian foster brother. The film has been read as a commentary on French colonial guilt post-September 11.

Haneke admits that he prefers to keep out of the debates about meanings, saying: "It's obviously not for me to decide what the contemporary parallels are. That's the job of the audience. "Unfortunately, the rise of extremism is always happening, over and over again, and after a decade there will always be new example. You could make an Arab film about Islamic extremism and that would be a different film, but it would have the same ideas underpinning it."

He looks like the stereotypical university director. His white beard falls below his chin and travels up near his eyes. His snowy hair is centre-parted and he's dressed all in black. He talks with the same authority that he shows in his directing. The son of the director and actor Fritz Haneke and the actress Beatrix Degenschild, Haneke was born in Munich in 1942 and grew up in the Austrian town of Wiener Neustadt. When his attempts to follow his parents' footsteps into acting failed, he journeyed to Vienna, where he studied psychology, philosophy and theatrical studies, three subjects that combine formidably in his oeuvre.

From 1967 to 1970, he worked as a critic, editor and dramaturge at the southern German television station Sudwestfunk, and it was in television that he first began directing. His career in celluloid can be divided into two geographical parts. His first five films, from 1989's Seventh Continent to 1997's Funny Games, offered criticisms of Austrian society, but by 2000 he started to work with the French actresses Binoche and Isabelle Huppert, and his movies, starting with Code Unknown, took on a more international outlook. First it was Europe, and then with his second go at making Funny Games with Naomi Watts and Tim Roth as the couple being terrorised, he looked towards the US.

Indeed, his decision to do a shot-by-shot remake of Funny Games in 2007 in America is the big curiosity of his career. The film is his only one to receive mainly bad notices and the poor reception of the remake still irks him. He says he decided to do it "because I knew that in the case of the first film that the fact that it was in the German language and was with unknown actors it didn't get the audience that it was aimed at in the first place. So when I was given the possibility of doing it in Hollywood with well-known actors, I took the opportunity to have another go with that Trojan horse, but of course it didn't work because people didn't see it. I have no idea why. For me as an interpretation to satisfy myself about it, I would say that most critics didn't write about the film but about the fact that it was a shot-by-shot remake rather than the incidences themselves."

Perhaps in retrospect he also feels it was a mistake to direct a film in English. When I meet him he has a German interpreter translating for him despite it being clear that he understands pretty much every word I say. "The White Ribbon is undoubtedly the most complex film that I've made," he argues. "It was also the most relaxed, because I automatically had everything under control because of the language. If you are in a restaurant and people are talking at the next table in your own language you can follow what is going on, but if it's a foreign language you don't follow what's going on. If, like me, you are a control freak it's extremely stressful if you can't understand what people say."

We are back on to the topics of power and violence that have featured in all his work: the mass suicide in his 1989 debut, The Seventh Continent, the murder in Benny's Video (1992), the killing spree in 71 Fragments of a Chronology of Chance (1994), torture in both versions of Funny Games and the self-mutilation in the exceptional The Piano Teacher (2001), starring Huppert. This fascination with cruelty and violence is something that he himself finds befuddling. He says of it: "You don't have to be personally affected by something to be interested in it, to want to find out more about it and get explanations. There isn't some sort of simple psychosocial explanation that can be used for these things. I'm often asked, for example, why my films are so dark and I don't really have an explanation for that. Only the devil knows."

One of the reasons that the violence depicted in his films has so much power is that he rarely shows the key incident on screen. Haneke is the master of the off-screen space, the events that the audience know are happening but the director has decided not to visualise. In this way, the Austrian auteur is able to engage with the imagination and subconscious of the spectator. He says that what is important is not what takes place in the film, but that the audience is still asking questions when they leave the cinema. He believes the images that are conjured up in the mind are far more personal and powerful than anything he can create on screen. He cites the German writer Theodore Fontane as a major influence on The White Ribbon in this regard. Fontane is a writer who leaves much to the imagination of his reader.

His directing work is not limited to the screen and over the years he's put on several works in the theatre. He has directed work from Strindberg, Goethe, Bruckner and Kleist in Berlin, Munich and Vienna. In 2006, he took on Mozart's Don Giovanni at the Paris National Opera. In addition he is also a professor of directing at the Vienna Film Academy. Having made The White Ribbon in Germany, he is returning to France for his next directorial effort, in which he will once again collaborate with Huppert, who just happened to be president of the jury at Cannes last year. Although the fact that the film is sweeping up awards is proof, if any were needed, that the decision was an unbiased one. He says he's returning to France because "this is where the actors that I wanted to use live". He's also persuaded the My Night With Maud actor Jean-Louis Trintignant to come out of retirement in the story about a man struggling to deal with the fact that his body is unable to do what his mind wants to. That's unlike the director, who seems to be able to do anything as long as he has a movie camera at his disposal.