Anna Seaman

Dubai-based artist Lara Assouad is one of 11 artists shortlisted for the prestigious Jameel Prize, awarded to a contemporary artist or designer inspired by Ismaic traditions. Anna Seaman rounds up the other 10 shortlisted nominees up for the award.

David Chalmers Alesworth

This British artist divides his time between the United Kingdom and Pakistan, where he lived for more than 20 years. His textile work, which will be shown in this exhibition, began in 2005 and stemmed in large part from his relocation to the historic city of Lahore — also known as the City of Gardens.

For his labour-intensive work, the artist takes carpets made in Iran and Pakistan and re-embroiders them with new patterns of famous gardens. So in Garden Palimpsest (2012), for example, he embroidered an image based upon the Versailles Palace gardens onto a 150-year-old carpet fragment. The idea is not to show the West obscuring the East, but to explore how the two influences become intertwined, like plants in a garden.

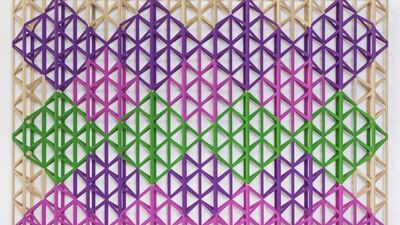

Rasheed Araeen

Born in Pakistan in 1935, Araeen has been living in London since 1964 and has made a name for himself as a pioneer of minimalist sculpture in the United Kingdom. He began his career as an engineer and signs of this can be seen in his highly recognisable artworks. He is best known for his formal, geometric and brightly-coloured sculptures, often created from simple, sometimes industrial, materials. A self-taught artist who creates art based on his experiences, he describes the fundamental idea behind art as pursuing the making of beautiful things. In this exhibition, he will show two pieces — the sculpture Spring Come, Happiness Come (2015) and Al-Ghazali Al-Ghazali Al-Ghazali Al-Ghazali (2010 to 2011), which depicts in acrylic paint the name of the Muslim philosopher Al-Ghazali inscribed four times on the canvas.

Canan

Canan, who is Turkish, identifies herself as a feminist artist. She questions domains of power and gender politics and is one of the leading defenders of women’s rights in Turkey. She uses performance, miniatures, video and photography to make a commentary on present-day Turkey and its recent history. Her work is steeped in the visual language of the Ottomans, notably miniature paintings and the use of gold leaf. The show Resistance on Istiklal Street (2014) is a representation of the resistance during the Taksim Gezi Park protests in Istanbul in 2013. The city is depicted as inspired by the works of Ottoman cartographers. Bosphorus Bridge (2014) is another miniature painting, which shows protesters struggling to reach Gezi Park while police use water cannon and tear gas.

Cevdet Erek

Turkish artist Erek works with sound, space and rhythm. He creates sonic and 3-D pieces about the structure of spaces and, more conceptually, of times. He also investigates the way we try to measure and organise ourselves within space and time. For the Jameel Prize he will show the Ruler series, in which he has taken the ruler, the traditional measuring instrument, and converted it into an instrument representing time. Ruler Day Night (2011) uses the daily prayer times to mark the sequence of day and night as a repetitive and subtly-changing black-and-white pattern. Ruler 100 Years (2011) works on two levels. The years before the Turkish alphabet reform in 1928 (replacing Arabic script with Latin script) are shown in Arabic, and the dates coming after in Latin. It also refers to the shift from the Islamic calendar to the Gregorian calendar in 1926.

Sahand Hesamiyan

Although he uses heavy materials such as metal sheets to make his sculptures, Sahand Hesamiyan’s work is largely based on metaphysical concepts. Born and raised in Iran, his art is a contemporary interpretation of traditional Iranian geometrical shapes — dissecting them into patterns and reshaping them into free-standing sculptures. He uses these forms to explore the infinite and, with his skill, infuses a lightness into the industrial materials. For this exhibition he will show a paper maquette of Khalvat, a giant steel sculpture first shown at The Third Line gallery in Dubai in 2014, and Nail (2012), an emblematic and arresting symbol of the crucifixion. Hesamiyan is represented by The Third Line.

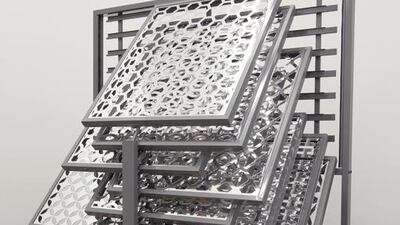

Lucia Koch

Brazilian artist Lucia Koch says her practice came from an investigation into what makes a space become a place or a living organism. She found that light and air are the vital substances and, as such, her artwork operates by filtering them. She also has a fascination with surfaces arranged in patterns such as mashrabiyas (lattice window coverings), which have been a part of Brazilian houses since the 16th century, when Portuguese settlers bought Islamic traditions with them. The two works on display from her series Construction Materials (2012) are a series of screens on sliding panels, which indeed play with light, reflection and spatiality.

Ghulam Mohammad

Ghulam Mohammad is an artist who uses words and language as a medium to create paper collage. In his native Pakistan, he collects books from Sunday markets and cuts out individual letters with painstaking precision. He then uses these to create his art, which is often made up of layers and layers of these letters, which are enriched with a new aesthetic meaning. The process is as important as the final product for this artist, who sees his work as freeing the original words from their pages.

He is showing five works from his Untitled (2014) series, which demonstrate the highly intricate work.

Shahpour Pouyan

Shahpour Pouyan’s work is a commentary about power, domination and possession through the force of culture. The Iranian’s work revolves around singling out particular objects, the images of which captivate him. His series of ceramics called Unthinkable Thought (2014) shows different forms of domes — architectural structures long used as expressions of power and a celebration of power and wealth. Pouyan uses traditional Islamic pottery techniques to make his models of domes from Europe and the Middle East, to show that humanity is essentially the same no matter what era or area people live in. Represented by Lawrie Shabibi gallery in Dubai, these works were shown in the city in 2014.

Wael Shawky

Prolific Egyptian artist Wael Shawky is showing his film Cabaret Crusades: The Path to Cairo (2012). This film is the second chapter of his Cabaret Crusades trilogy, which recounts the history of the Crusades from an Arab perspective. Although Shawky began the series before the recent political and social upheavals in the region began, there are a lot of parallels between the two periods. He created marionettes, drawings and objects to make his animated films — which are based on the book The Crusades Through Arab Eyes by Amin Maalouf (1983) — and to describe the specific horrors of religious wars with crafted characters, music, scenography and speech. He says his artistic fascination is the idea of translating a text into a new visual experience.

Bahia Shehab

Egyptian art historian Bahia Shehab has long been fascinated with the Arabic script for “no”. In 2010, this professor of graphic design at the American University in Cairo began a project called A Thousand Times No (2010). She collected 1,000 different shapes of the word “no” (lam-alif in Arabic) in Islamic history and put them in a book. After that, she created a Plexiglas curtain made of these 1,000 visuals, which was exhibited in Munich. She portrays not only the richness of Islamic culture, but also makes a bold political statement about the state of the world today.

aseaman@thenational.ae