Hundreds of thousands of people travel every year to Mecca to pray inside the Grand Mosque and visit the house of Allah, the Kaaba. And every year, as per tradition around Haj time, on the 9th day of the Islamic month of Dhu’l Hijja, the Kaaba gets a new kiswa, a cover made of pure silk, dyed in black and padded with white cotton fabric.

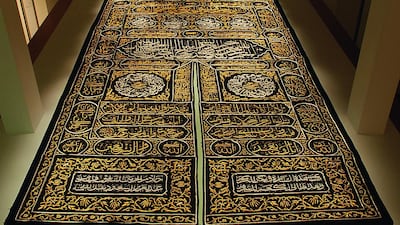

Weighing more than 670 kilograms, Quranic verses are beautifully and skillfully embroidered in different calligraphic forms by more than 200 talented artisans onto the kiswa, in threads of pure gold and silver. Kiswas and other sacred textiles are the subject of the latest book released by the Sharjah Museum Department, Islamic Textiles, from the Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilization.

Sold for Dh70 at the museum’s shop, the 76-page book is designed in black and gold, and features some of the most sacred and important textiles from Mecca and Madina, as well as the Ottoman period, Turkey and Egypt.

In awe of the beauty and sacredness of the kiswa, often the worshippers do not have the chance to read what has been written along the cover of the Holy Kaaba as hundreds of devotees push and shove wanting to touch Al Hajar Al Aswad, the black rock, at the Kaaba’s eastern corner.

The Holy Kaaba represents the Qibla, the direction in which Muslims all around the world face to perform their prayers.

Different parts of the cloth have different designs and different stories. For instance, the curtain for the door of the Kaaba, is known as sitara, burdah or burqu, and is one of the most elaborately designed parts of the kiswa.

The sitara’s appearance has changed little over the centuries, embroidered with invocations to Allah, supplications and Quranic verses.

On the two bottom panels, enclosed within rectangular-shaped designs, the name of the person who “gifted” the kiswa is embroidered with the name of its maker. An example of a sitara that can be seen close up lies at the Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilization. Dated 1421 Hijri / 2000 AD, it reads in embroidered calligraphic Arabic: “This sitara was made in Makkah al-Mukarramah and gifted to the honoured Kaaba by the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques King Fahd bin Abd al-Aziz bin Al Sa’ud. May Allah be pleased with it.” King Fahd ruled Saudi Arabia from 1982 to 2005.

Manal Ataya, director general of the Sharjah Museum Department, says the book has been released as part of the department’s contributions to Sharjah’s celebration as Capital of Islamic Culture in 2014.

“At the same time, it does offer a lot of fascinating information about the textiles that Muslims come across when visiting the holy places of Mecca and Madina during Haj [major pilgrimage] and Umrah [minor pilgrimage].”

Just how important it was for the Holy Kaaba to get its new clothes each year was reflected in how, back in 1927, Saudi King Abdul Aziz, founding father of Saudi Arabia, ordered the establishment of a factory dedicated to the manufacturing of kiswa in Mecca.

“Initially, precious and luxurious textiles were sent to the Kaaba in particular from all over the Islamic world. Under the Mamluks, the major textile-making centres were in Egypt and Syria, later – under the Ottomans – joined by specialised workshops in Bursa and Istanbul. Since the early 20th century, all the religious textiles for the holy places are made in Mecca,” Ataya elaborates.

Since 1962, the Umm al-Joud factory in Mecca has been the most recognised and dedicated centre for the making of the kiswa.

“Religious textiles from the Islamic world have the greatest significance for Muslims worldwide, as they served and continue to serve to honour the holy places in Mecca and Madina. Most important of course are the hangings for the exterior and interior of the Kaaba, but many other ceremonial textiles were also produced to honour significant places in the Mecca mosque precinct and the mosque and tomb chamber of the Prophet Mohammed in Madina,” says Ataya. “Even after use, these textiles continued to hold great spiritual meaning due to their direct contact with the holy places of Islam. The calligraphic designs on the pieces are carefully chosen to reflect a textile’s specific function and location. These are always taken from the Holy Quran, the words of God – which adds to their exalted status in Muslim ritual and culture.”

One of the most interesting textiles is found in a symbolic silk bag. Dating back to 1987, the green silk bag with its golden words, holds the key of the Kaaba.

For centuries, a special bag has been prepared every year to receive this key and together with the kiswa, the key bag is presented to the most senior representative of the Banu Shayba, the direct descendants of Uthman bin Talha, the man chosen by the Prophet Mohammed to guard the Kaaba keys “until the Day of Judgement”.

The Quranic inscription on this bag is taken from Al-Nisa’ sura (chapter), verse 58:

“Verily! Allah commands that you should render back the trusts to those to whom they are due…”

Made nearly exclusively for the holy places of Mecca and Madina, Islamic textiles were greatly honoured, carefully guarded, preserved and stored after use. Ataya says: “Many were given to Muslim dignitaries and officials, who took great pride in possessing and holding on to them.”

The oldest textiles at the museum are related to Mecca and Madina and date back to the 17th and 18th centuries. Made with fine silk from Bursa and Istanbul, they were used to drape the Kaaba and the Tomb of the Prophet Mohammed in Madina.

“The first example shows a distinct zigzag design, combining the Profession of Faith [shahada] with references to the majesty of Allah, an arrangement that can still be observed in very similar form on the all-black kiswa cover that drapes the Kaaba to this day,” says Ulrike Al Khamis, the senior strategic advisor on Islamic and Middle Eastern arts at the Sharjah Museum of Islamic Civilization

“The second piece was part of a hanging that draped the inner walls of the tomb chamber at the mosque of the Prophet in Madina. It shows finely calligraphed prayers to Allah and in remembrance of the Prophet, again contained within zigzag bands.”

Another interesting fact is that the black cloth wasn’t always black.

“In early Islamic times, the Kaaba could be covered with a wide range of luxurious, multi-coloured textiles. A black drape was adopted in the 12th century. It is also assumed to have been around that time that the characteristic belt [hizam] around the upper part of the Kaaba was adopted,” Al Khamis says.

“Initially, this section was woven. An embroidered border, soon followed by other embroidered elements, was only adopted in the 18th century under Ottoman rule. The distinct colour scheme of black, gold and silver was introduced in the early 20th century under Saudi rule.”

A great wealth of stories and history, the book covers different holy textiles for different segments of the Kaaba and other holy structures and sites.

“The book is designed to be informative and educational, but it also has a contemplative dimension. In other words, it introduces every religious textile in the museum from an art-historical as well as from a spiritual point of view,” Ataya says.

“To that end, the photograph and text of each piece is further enhanced by a special feature – a double page that opens out to reveal the Quranic verses rendered on it – presented in Arabic and English.

“We hope that the book will be interesting for a wide range of readers, from academics and students, to members of the public who would like to gain a glimpse into the fascinating world of religious textile production and the broader historical, social and spiritual contexts surrounding it.”

Follow us @LifeNationalUAE

Follow us on Facebook for discussions, entertainment, reviews, wellness and news.