For centuries, tribesmen in Oman have proudly worn khanjar around their waists. Today, the image of the khanjar – evocative of sheikhs, sultans and age-old traditions – adorns the country's flag and coat of arms.

The ceremonial blades are also still worn for official functions across the country. No wedding or big meeting is complete without the dagger: its very presence enhances the prestige and solemnity of any event.

There is not a weapon in the Gulf that has earned the reverence of the khanjar – its status as a symbol is cemented through art, poetry – and literature. Understandably, its craftsmanship is every bit as impressive as its cultural significance.

One dagger can take months to make

It’s an art Mohammed Al Sayegh has known nearly his entire life. A master craftsman from the coastal city of Sur, near Oman’s eastern tip, Al Sayegh is the scion of a family that has been making khanjar for more than 100 years, their mastery appreciated from the Batinah plains to Shofar.

It's an onerous process, with each step requiring the khanjar-maker's deft hands. One dagger can take from a few weeks to several months to make.

"The silver, the threading, all of it we do by hand, big or small. The work is strenuous and very tiring," Al Sayegh says. "The first thing you do is measure how long the khanjar will be. In Sur, khanjar measurements start from five inches [12.7 centimetres] and go all the way to six. Should it exceed six inches, it will be a specially made khanjar, large like those in Nizwa. Daggers below five inches are for children.

"After that you cut the leather in the length and shape that you want. We then get wood, usually teak, cut and clean the leather from both sides then fix the leather to the wood. The silver work is done by itself, it has its own process."

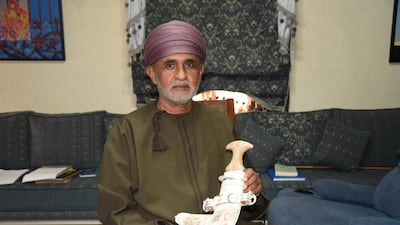

Holding one of his family's own daggers, he points out each part with withered hands, starting with the "qarn" (hilt or horn) at the top, then the "toq" just below, going down to the "sidr" (chest), its floral patterns sprouting outwards in all directions. "After fixing the leather to the wood, we then fix the sidr, then the toq, and then what we call the 'tooms', which holds the khanjar. It will determine how it looks on the wearer. In Nizwa, for example, they prefer the khanjar to stand straight up. In Sur, we like it slanted to the side."

It is a process Al Sayegh has done time and time again, a traditional method he learnt in the workshop of his father. "My brother, myself, my father, my grandfather, and those before them – we all worked on khanjar. You can say that our family trade is making khanjar, going back over 100 years. We still have a small one made by my family in 1888.

“The craft was inherited from our ancestors, who passed it to our fathers and then to us. The ideas came down to us that way, there was no manual,” he says.

His childhood was tied to his father's workshop, where he learnt the secrets of the trade. "In the morning I would go straight to my father's workshop. I would clean the entire place. If I saw something had fallen, maybe a piece of silver or something else, I would pick it up, I would change the water, the charcoal, and make sure the workshop was ready. That was my routine."

Keeping the khanjar tradition alive

In many ways, Al Sayegh stands out. Not only is he among the few who know how to make khanjar, but he is also making sure his knowledge and techniques are passed down to the next generation. He has written a book, helps maintain two workshops and poured everything he knows into his own son, just as his father did with him.

"Five years ago, my younger son decided he wanted to make things in a workshop. He built one in the back of the house. I later joined him, showing him how to do it. Today, if anyone wants a khanjar we can make it for them. I have got older, my eyes are tired and I cannot work the same way I used to. Nowadays I am focused on passing my skill to others."

The Al Sayeghs are not the only ones keeping this time-honoured custom alive.

Hundreds of kilometres away in the historic city of Nizwa, another artisan has dedicated countless hours of his life to making khanjar. He is one of the few in the town's souq who can make them, with others simply ordering whatever dagger their customers require.

Khalid Al Tiwani was enamoured with khanjar for decades, eventually driving him to take up making them himself. "When I was young, I used to learn at home. At the time all women used to make khanjar belts and different khanjar pieces. They used to work with silver and leather. We saw our mother and older sister doing it, and decided to learn. We learnt a bit but not everything because sometime after 1980 most women stopped making them at home," says Al Tiwani.

After his studies, he joined his father working in a silver and khanjar shop. He loved the artefacts they handled day after day and soon found his desire to learn rekindled. "When I began working with my father, I decided to try learning again. My brother and I asked everyone we met who could make khanjar to teach us. Now we know how."

For Al Tiwani and his brother, making khanjar is a perfect way to unwind and escape the monotony of sitting in a shop. "We don't always find the time but when we do, even if it's just for 15 minutes, we work on our khanjar. Sometimes when we don't have customers or even when we just want to keep ourselves busy, we go back to working on khanjar."